Forgotten, Famous and Favourite Nobel Literature Prize Winners (1929-36)

120 Nobels Challenge WEEK 5: Thomas Mann to Eugene O'Neill

On 28 October 1929, the American stock market crashed, plunging the Western economies into depression, most severely in the USA and Germany. Two weeks later, the Swedish Academy awarded the Nobel Literature Prize to Thomas Mann. He was the greatest German writer before the Fall. Within a decade, he would become an eminent cultural prize of the new American century.

Since 1901, 120 writers have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Some are forgotten. Many remain famous. A few became notorious for reasons that might surprise you and change your understanding of modern history. Discover them all in the 120 Nobels Challenge.

You can join the Burning Archive’s 120 Nobels Challenge with these five steps:

Read this post with stories of seven Nobel Laureates

Follow the links to free resources to read at least one Nobel Prize writer

Leave me a comment about any of the forgotten, famous, or favourite Nobel Literature Prize winners you have enjoyed

Join the live call (or watch the replay) discussing a month of Nobels

Share your thoughts with other readers on the Sunday Archive Reading Thread.

The inaugural workshop is live on 16 July 4.00 pm AEST, replayed in 17 July post.

Check my Wednesday post for all the details. If you want to join me live, book here.

This week, we read the winners from 1929 to 1936. North Americans win the Prize for the first time. A Russian wins the prize for the first time, but only an emigre who fled the Soviet Union. The world enters in 1931 the Last Imperial War, in Richard Overy’s term (Blood and Ruins). Many demons and revolutionary dreads haunt the prize. But some great art endures.

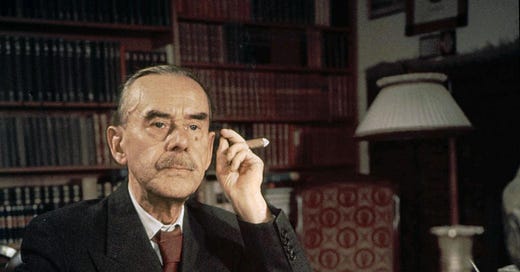

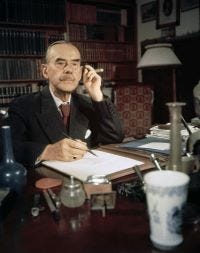

1929 Thomas Mann (1875–1955) Germany

Mann was the last Nobel laureate of Europe before Fascism when Germany was the culturally dominant power of the West. His prize marked a turning point towards Anglo-American cultural hegemony. After his prize, Germany fell to fascism, Mann fled Germany, and the USA courted the great man of letters. In 1938, he emigrated to USA. He would become the archetype of the American Century’s adoption of the exiled grandees of good European culture.

Mann was the son of a successful family business in Lübeck. His family’s vocation taught Mann discipline. His novel, Buddenbrooks is a tribute to the virtues of this commercial world. In his twenties, he moved to Munich, where art for art’s sake culture revolted against his family’s sensibility. Salons led by Stefan George believed themselves to be aesthetic übermensch. Mann began a day job in an insurance firm, and at night began to write.

He married Katia, who managed the writer’s life. While Mann wrestled with his exquisite contending sensibilities that came from the rich German cultural heritage, Katia managed his day and reputation.

Despite the marriage, Mann was tempted by sublimated homoerotic fantasies. The 1912 novella, Death in Venice presented a great writer who lingers in cholera-infested Venice while obsessing about an adolescent boy, Tadzio. The story was made into one of the great arthouse films of the 1970s by Visconti and Dirk Bogarde.

When war broke out in 1914, Mann rallied to the monarchy and Germany as a deep civilization that had been unfairly attacked. But lack of success in the war provoked Mann to retreat into political ambiguity. His brother attacked him as a weather-vane, always pointed to the best patron. Mann responded with eloquent ambiguity, after the German and Russian Revolutions, in Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (1918). Mann argued there were no longer any political interests worth defending. He expressed scepticism about the new Weimar Republic. His doubts were championed by antidemocratic forces. Weimar democrats suspected Mann as a bourgeois of old Imperial Germany. By 1922 Mann recanted and declared allegiance to the fledgling democracy. He lost the trust of both disappointed conservatives and suspicious democrats. As so often with literary giants, this non-political man should have kept to his knitting.

His knitting after all was brilliant. In 1924, he published the work he had begun in 1912, Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg). Mann described it as a portrait of the “European mentality and intellectual dilemma of the first third of the twentieth century.” A young engineer, Hans Castorp retreats with mild ill-health, suspected as tuberculosis, to a sanatorium in Davos. There he meets and converses with the Grand European culture that was on its way to a murderous war. The echoes with today’s world are eerie.

The novel is difficult to translate, full of irony, and stocked with cultural references that were known to well-educated Europeans in 1924, but are forgotten today. Yet it concludes, reflecting on Castorp’s march to the meat grinders of Europe

“And out of this worldwide festival of death, this ugly rutting fever that inflames the rainy evening sky all round - will love someday rise up out of this, too?

Dr Faustus (1947) was Mann’s last great novel reflecting on the tragedy of the European spirit. It too has echoes of today, but time is short, and I will write more on Mann another day.

1930 Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951) USA

Sinclair Lewis was the first American to win the Nobel Prize. He authored popular novels that mocked American commercialism within safe limits.

Babbit satirised the modern commercial middle-class so well that the name of the central character became a term to describe a business or professional man who conformed without qualms to the standards of the American middle-class.

Lewis himself reflected the demons of America in the 1920s. His marriages were troubled and led to divorce. He was driven by financial, not artistic goals, and so his writing’s esteem plummeted after his death. He fought feuds with a rival novelist, Theodore Dreiser, over plots and women.

And he fought the demon drink. The USA prohibited alcohol in 1919 through the Volstead Act. But Prohibition, the great reform of WASP America, failed. It only fostered a hard-drinking culture of success. Lewis was such a high-functioning alcoholic. But alcohol undoes even the most grandiose. By 1937 Lewis had fallen from the high of the Prize to rock bottom. He sought treatment for alcoholism in a psychiatric hospital. His doctors told him he could live win 1935, one of the most influential social movements of the American century. But Lewis ignored both doctors and AA and died of advanced alcoholism in 1951.

His reputation enjoyed a brief revival in the 2010s because his novel, It Can't Happen Here, seemed to predict American fears that authoritarianism could come to America in the form of alt-right populism. Lewis imagined America electing a fascist president. He portrayed the new continent indulging the bad habits of the Old Continent’s strong man politics.

And might not be so bad, with all the lazy bums we got panhandling relief nowadays, and living on my income tax and yours—not so worse to have a real Strong Man, like Hitler or Mussolini—like Napoleon or Bismarck in the good old days—and have 'em really run the country and make it efficient and prosperous again. 'Nother words, have a doctor who won't take any back-chat, but really boss the patient and make him get well whether he likes it or not!"

"Yes!" said Emil Staubmeyer. "Didn't Hitler save Germany from the Red Plague of Marxism? I got cousins there. I know!"

But the novel reads like pulp political fiction. It misunderstands America and Germany in the 1930s. Lewis will not be going on my reading list. You can read his major works here or in many libraries, if you disagree.

1931 Erik Axel Karlfeldt (1864–1931) Sweden

The 1931 Prize was unique. It went to a dead man. But that is not all. This dead man had a unique privilege. For two decades he had served as the Secretary of the Swedish Academy that awarded the Nobel Prize.

Karlfeldt was born Erik Erickson in traditional rural Sweden where people used patronymics, not distinct family names. He adopted Karlfeldt as part of his emergence as a writer and an individual in modern urban Europe.

He became a poet, more focussed on imagination, than the realist social concerns that had won so many Nobels before. He turned away from politics, and pursued poetry for poetry’s sake.

His first collection of poems in 1895, however, had one foot planted in both Sweden’s rural folk ‘song’ traditions and its European classical culture of the dichter.

His poetry was deeply rooted in Swedish as a minor European language. It evoked the language of the Karl XII Bible of 1703, which was the epitome of Swedish. as in English the King James edition was. Only one Karlfeldt book has been translated into English. Yet within Swedish, the experts say, a few of his poems remain Swedish but untranslatable classics.

Two final lines of “August Hymn” from Flora and Pomona (1906) can be presented in both English and Swedish.

The one who bears the crown of autumn on his brow

dreams and smiles, but laughs not like before

Den som bär höstens krona över pannan

drömmer och ler, men skrattar ej som förr

However, if you love classical music, you may have heard his lyrics His songs were set to music by Sibelius and other Swedish composers - for example, here. Swedish speakers and the curious can listen to one recital in Swedish I found on Youtube here

1932 John Galsworthy (1867–1933) Britain

Galsworthy was the first truly British writer in English to win the Nobel Prize. Kipling came from Mumbai. Tagore was a lesser subject of empire. Yeats and Shaw were Irish, and Lewis a damned American.

Although it took 31 years for the Swedish Academy to honour Britain as the supposed world hegemon, they chose the perfect embodiment of late British empire conservatism.

Galsworthy was a child of the British Empire in the age of steam globalisation. Born to a wealthy family, schooled at Harrow and Oxford, he prospered in the English age of finance, shipping, insurance, and colonies. Galsworthy cherished English values of fair play, gentlemanly behaviour, love of the countryside, and the village green.

His most famous work, the Forsyte Saga spoke of wealthy, well-spoken Britain with mild but loving satire. The novels trace three generations of a large upper middle class English family from the turn of century to the era after World War One. It makes an interesting contrast to Thomas Mann’s great novels of the European worlds of commerce and culture in Buddenbrooks and Magic Mountain. In my view, it does not hold a candle to the greater German maker.

In one chapter, “Passing of an Age”, Galsworthy described imperial Britain at the turn of the century.

“The Queen was dead, and the air of the greatest city upon earth grey with unshed tears. Fur-coated and top-hatted, with Annette beside him in dark furs, Soames crossed Park Lane on the morning of the funeral procession, to the rails in Hyde Park. Little moved though he ever was by public matters, this event, supremely symbolical, this summing-up of a long rich period, impressed his fancy.”

Forsyte Saga (volume one), p. 603

Still, even imperial conservatives know some wisdom.

“Life calls the tune, we dance.”

John Galsworthy

He knew generosity too. On a boat trip to Australia in 1892, he befriended the Polish first mate on the ship. This man was writing his first novel in his cramped quarters. The first mate was Joseph Conrad, author of Heart of Darkness. Galsworthy became his friend and financial supporter. Conrad inspired the lesser talent to become a writer, though not with Marlowe’s dark vision of empire.

Galsworthy loved the world of bourgeois Edwardian Britain. But like the sanatorium in Mann’s Magic Mountain, this cultured world was doomed. Virginia Woolf once wrote, “On or about December 1910 human character changed.” The smart set in Bloomsbury at least abandoned Galsworthy’s aesthetic. Then World War One and ensuing political and social turmoil destroyed his gentlemanly world.

But the 1920s brought him fortune and fame. The Nobel Prize sealed the honour. At last, Britain had won a Nobel, in time to lose an empire. Galsworthy died two months after the Swedish royals pinned the medal to his chest. Back in Bloomsbury, Virginia Woolf wrote in her immortal diaries that she was glad the “stuffed shirt” had died.

His literary reputation outside Britain would have collapsed too. But in 1967 and again in 2002 the Forsyte Saga was made into television series that sentimentalised British imperial nostalgia. Galsworthy would be proud.

You can read online his complete essays, plays, and all three volumes of the Forsyte Saga.

1933 Ivan Bunin (1870–1953) Russia

After the first true Briton in 1932, the Academy honoured the first true Russian in 1933. But he was not a Soviet man. He was the emigre, Ivan Bunin, who had fled revolutionary Russia in 1918 and lived in France.

Ivan Bunin was a short story writer in a tradition of Russian writers who despised the Slavic soul and sought refuge in the West. His aristocratic family went back to Lithuanian nobility in the 16th century, and Bunin was proud of the heritage of his family.

Although he met Tolstoy and Chekhov, greater writers ignored for the prize, he took a less compassionate approach to the poverty of Russian peasant life. He spurned village life and idealised the gentry as ‘‘rare oases of culture’ in a brutal country. He blamed the “Slav’s psyche” for degeneration in literary standards, spiritual life, and society. The outbreak of World War One convinced him “the ancient beast is alive and strong in man.”

The war ended badly for the Russian gentry, but liberated Bunin from his psychic prison. The February Revolution found Bunin sheltered in a friendly country estate, where his companions in the bourgeoisie sheltered in fear that the peasants would burn the house down. By October, Bunin had moved to Moscow where he witnessed the October Revolution and kept a famous diary of his response to events, Cursed Days: diary of a revolution.

“I am writing by the light of a stinking kitchen lamp, using up the last of the kerosene. How sick, how outrageous this all is. My Capri friends, the Lunacharskys and the Gorkys, the guardians of Russian culture and art, express self-righteous anger when they warn New Life about abetting “tsarist sympathizers.” What would they do with me now if they caught me writing this criminal tract by a stinking kitchen lamp or trying to hide it in the crack of the ledge?”

― Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin, Cursed Days: Diary of a Revolution

By May 1918 he had fled to Odessa via Kiev. In his diary, he wrote “the entire Russian world is becoming indecent trash.” Amidst the chaos and death of the Russian Civil War, Bunin fled Odessa, with British and American assistance, on one of the last boats carrying the defeated Whites and hated aristocrats to the refuge of emigre life in Paris.

There Bunin emerged as a leader of the Russian emigre community. Their story is told, from the perspective of a British journalist, by Helen Rappaport in After the Romanovs: Russian Exiles in Paris between the Wars. Many would move onto America, like Mann did in the 1920s and 1930s. The greatest of these emigre writers was Marina Tsvetaeva. Unlike Bunin, she would return to the Soviet Union and die a tragic death. But that is a story for another post.

Bunin’s stories are often tales of passion snuffed out by darkness. He celebrated ecstatic unions as brief moments of peak experience in an undistinguished life. He wrote as he lived, a man in exile who had many affairs. He endured the Great Fatherland War, when the Germans sought to enslave his hated fellow Slavs, in the city of perfume, Grasse, in the French Riviera. He died in a Paris apartment in 1953.

You can read a guide to his works in Russian here, and his collected stories in English here.

1934 Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936) Italy

Luigi Pirandello was the most artistically revolutionary of the Nobel Laureates before World War Two. He wrote in novels, short stories and over 40 plays. His plays changed European drama forever. His provocative, absurdist experimental drama parted the seas of literary modernism. He opened the stage on which Ionesco, Artaud and Beckett would stage the theatre of cruelty and alienation.

You may have heard of his play, Six Characters in Search of an Author. It created a scandal similar to the famous reaction to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, which also changed modern music and ballet forever. It premiered in Rome in 1921. The audience screamed in protest, “Manicomio!" ("Madhouse!") and "Incommensurabile!" ("Off the scale!"). It shattered theatrical convention. How?

Pirandello first conceived the story as a novel. But by realising this theatre within the theatre he revolutionised theatre. An author is haunted by six characters. They ask the author to bring them to life and discuss their relationship with the audience watching the play. It is an inner drama about writing and performance, a revolutionary investigation of the masks and illusions of dissociated characters, and an attack on the ‘bourgeois’ idea that they can know the truth or control reality. It plays with the idea of what is reality and what is make-believe.

Towards the end of the play a character appears to be dead. The actors and director dispute what is real and what is not. They address themselves, the author, and the audience.

LEADING MAN: Dead, my foot! It’s only pretending, pretending! Don’t you believe it!

OTHER ACTORS ON THE RIGHT: Pretending? No, it’s real, it’s real! He’s dead.

OTHER ACTORS ON THE LEFT: No. It’s just make-believe, make believe!

FATHER: How can you say make-believe? It’s reality, ladies and gentleman, reality!

Pirandello’s drama pioneered the aesthetics of the mid-twentieth century. Today such meta-narratives are common, even dated. In the 1920s Pirandello’s drama was a revolutionary outbreak against the nineteenth century conventions of naturalism and symbolism. Pirandello was not alone. From the 1900s, Stanislavski had pioneered new styles of drama at the Moscow Theatre. Traditions from outside Europe inspired the outbreak. In 1931 Antonin Artaud saw a Balinese dance troupe performance in Paris, which shook him from European conventions, and led him to write his manifesto on the Theatre of Cruelty in 1938. The new drama found its most famous expression in Samuel Beckett’s post-war play, Waiting for Godot.

Artaud’s cruel theatre is an acquired taste, but Pirandello and Beckett managed to combine experiments in absurdity with humour that made us laugh at our own illusions. Indeed, Pirandello wrote an essay on the philosophy of humour in 1908.

“Life is full of strange absurdities, which, strangely enough, do not even need to appear plausible, since they are true.”

― Luigi Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author

But the revolutionary drive to smash conventions had strange bedfellows in inter-war Europe. As Modris Ekstein identified in Rites of Spring: the Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age, we want the avant-garde and reel from storm-troopers. But in the modern age they bore a family resemblance. In Mussolini’s Italy, Pirandello claimed it was a time for Caesars so that poets like Virgil could no longer exist. Like many artists of the 1930s, he was drawn into the growing storm of fascism, although he defended himself from the charge of acting as a precursor of fascism in December 1934 in an essay entitled, “Am I a destroyer?”

You can read Six Characters in Search of an Author here, listen here, and watch a performance on Youtube here.

No prize was awarded in 1935.

1936 Eugene O'Neill (1888–1953) USA

A very different kind of playwright, Eugene O’Neill, won the next Nobel Prize.

O’Neill was a child of a middle-class Irish mother and a philandering father actor. His early family life became immortalised in Long Day’s Journey into Night. His mother withdrew from the world after his father’s betrayal. His father sacrificed artistic integrity for financial success. Their fates haunted Eugene, but enabled him to study at Princeton and to dream of writing.

He read Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Yeats, Wilde, Ibsen, Strindberg, and the German Nobel laureate, Hauptmann. He explored the underworld of the early 20th century cities, like many modern Bohemian artists. It was a world of gangsters, outcasts, and above all addiction. He married early but fled commitments to spouse and children by working as a seaman in the age of steam globalisation. Free of commitments, O’Neill travelled to Buenos Aires and developed an alcohol problem. By 1912 divorce and addiction drove O’Neill into shame, and he attempted suicide.

His life turned around when he entered a sanatorium in Connecticut like Hans Castrop in Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. In 1914 he sought his father’s help to be an artist or to be nothing. He moved to Greenwich Village and established himself as a workhorse of Broadway. From 1916 he wrote plays for theatrical seasons, year in and year out to the mid 1930s. The plays grew in quality and variety: short plays, long plays, plays based on the ancient Greek Oresteia (set in America after the Civil War), and plays featuring female characters, like his mother. The relentless content creation culminated in a personal breakdown in 1934 and 1935. He would not stage a play again on Broadway till 1946.

The Prize came when O’Neill was a wreck. But unlike most Nobel winners, his greatest literary achievement came after the Prize. O’Neill would spend a decade coping with worsening physical health and failing to complete his projects. After ten years of writing failure, he abandoned a “possessors dispossessed cycle” based on Ancient Greek models. He wrote three great dramas based on his early life. A Moon for the Misbegotten sprang from memories of his mother and his alcoholic brother. The Iceman Cometh is set in 1912, the year O’Neill attempted suicide, and portrayed lives misled by alcohol and saving illusions. Long Day’s Journey into Night portrayed the family life and disappointments that had haunted O’Neill so long.

O’Neill wrote Long Day’s Journey into Night out of that lifelong torment and did not intend the play to be staged. He stipulated the drama would not be printed until 25 years after his death. It portrayed the Tyrones. This middle-class family was driven by sorrows to a tragic end.

“None of us can help the things life has done to us. They’re done before you realize it, and once they’re done they make you do other things until at last everything comes between you and what you’d like to be, and you’ve lost your true self forever.”

― Eugene O'Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night

After these plays O’Neill fell into silence and died in 1953. His wife, Carlotta, outlived him for 20 years. Carlotta brought the plays to the stage, and overrode O’Neill’s wish to conceal his great dramas. So, twenty years after O’Neill’s Nobel Prize, Long Day’s Journey into Night turned the American playwright into a literary legend.

You can watch a 1986 staging for television of the play, directed by British theatre legend Jonathon Miller on YouTube here.

Good reading, thank you. I read the Magician & found it really elucidating about Mann & his family. I hadn’t realised what a culturally important turning point he represents.

Sorry for the typos, but I wrote the above in the sun, and Substack doesn't let me edit, after I posted it.