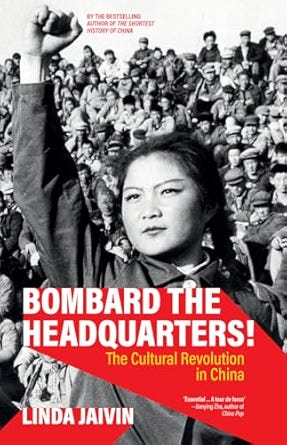

Bombard the Headquarters! The Cultural Revolution in China

Best history book introduction to China's “Ten Years of Chaos"

Welcome to the sixth week of my World History Tour of China. This week we look at the Cultural Revolution, referred to today in China as the “Ten Years of Chaos.” What is the best history book to understand the Chinese Cultural Revolution 1966-1976?

There are some long, dense, and difficult-to-read books on the Chinese Cultural Revolution. But I would not recommend them on this introductory world tour.

Thankfully, Linda Jaivin, who is the author of the Shortest History of China (the first China history book recommended in this series) has just written a brilliant 100-page gem, Bombard the Headquarters! The Cultural Revolution in China.

Brilliantly concise, this book enables you, in a weekend, to learn the core story of the “Ten Years of Chaos”, to grasp the main characters, including Mao and the Gang of Four, and to find out where to explore further in books and film.

And what is more, in a couple of weeks, I will be interviewing Linda Jaivin about her book and sharing her insights with you here. I can personally recommend the book. So why not buy Jaivin’s “tour de force” (Jianying Zha, author of China Pop) now?

Conflicting Histories of the Cultural Revolution

As I implied last week in my post on Farewell My Concubine, the Cultural Revolution in China has long intrigued me. I recall personal memories of watching television news reports of the Gang of Four and the Cultural Revolution. I have watched films, read histories, and asked people on my travels about it. I have thought about it not only as an aberration of Communism or a decade unique to China’s history, but as a human puzzle, with parallels to other historical and contemporary events. How do crowds become mesmerised by slogans and seduced by violence, whether in Beijing in 1966 or Paris in 1968 or in the USA in 2020 or the whole Western world in 2022? Why are intellectuals sometimes the cruellest instigators of violence? Why do we destroy our culture and our history? Why do we throw history into the flames of the burning archive?

The fifth and final part of Jaivin’s book, “The Long Shadow of the Cultural Revolution” records how the Cultural Revolution was metaphorically and literally a “burning archive.”

The Cultural Revolution left China with but a sliver of its material cultural heritage. In Beijing alone, Red Guards destroyed 4,922 of the city’s 6,843 registered ‘places of historical or cultural interest.’ They burned over two million books and three million artworks and pieces of antique furniture.

(Jaivin, p. 106)

Books did not burn alone. The Cultural Revolution killed, maimed, jailed, and scarred. Since 1976 a tradition of “Scar Literature” has developed which reflects on this trauma. But as in all cultures, memory, history and forgetting dance to many tunes. The Scar Literature has provoked a response by the current leadership of China that warns against “historical nihilism”, or as the Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey once more metaphorically wrote of Australia’s own memory wars, “black-armband history.” Discussion of the chaos is discouraged for fear of inducing more chaos. Many of the scarred may also, sixty years later, want simply to move on and forget, as I discussed in my piece on Red Memory. Dread Trauma. On a recent history of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (December 2023), which reviewed Tania Branigan, Red Memory: Living, Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution (2023).

Trauma is a place where memory, history and forgetting mingle uncomfortably. Our responses to the experience of trauma respond to different needs. Whether we respond by remembering, by forgetting, or by telling the fact-laden fables we know as history, is moment by moment uncertain as fragmentary images and torrential emotions pass through our minds. Am I back there again? Please, let me forget. Who hurt me so? Speak, Memory. Can I escape and live to tell my tale of overcoming the monster. Time to pen some history.

Jeff Rich, Red Memory. Dread Trauma. On a recent history of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (December 2023)

Jaivin mourns the loss of China’s cultural heritage, and sides with the outsiders and dissidents who seek to keep memory and history alive, despite an official will to forget. She urges us to face two shadows of the Cultural Revolution.

“Two shadows lie over the present. One is that of censorship, the command to forget, lest the past escape from control. The other is that of the Cultural Revolution itself, demanding to be remembered, lest the past rule the present.”

(Jaivin, p. 107)

The Story of Bombard the Headquarters!

Jaivin begins the story with Mao’s political pamphlet, Bombard the Headquarters! It was his declaration of cultural war in August 1966. It is a slogan of a political strategy that is evoked today by people far from Mao’s belief, such as right-wing USA nationalist strategist, Steve Bannon. Mao took the phrase from a popular poster, and accused his bureaucratic (‘deep-state’?) rivals of

…standing with the reactionary bourgeoisie, enforcing bourgeois dictatorship and shooting down the dynamic movement of the Great Cultural Revolution. They reverse right and wrong, confuse black and white, besiege and oppress revolutionaries, silence dissent, inflict white terror, and feel smug about it. They promote bourgeois arrogance and deflate the proletarian morale of the proletariat. Should this not wake us up.

(Mao Zedong 1966, quoted Jaivin, p. 3)

Some of the phrases jar these days. Most of the stratagems, however, are still followed if with less violence.

Jaivin tells the story in four parts.

In “The Buildup” Jaivin describes the first seventeen years of the People’s Republic of China. I discussed these events myself in my post on The Great Leap Forward this week.

In “Towards Civil War” Jaivin describes the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. She explains the resonance of the slogan, “Smash the Four Olds” (old ideas, culture, customs and habits). The leadership embraced cultural struggle to break the old society and to leap into the revolutionary future. In the words of Lin Biao, a main character and later victim of the Cultural Revolution, “Armed struggle can only touch the flesh; only cultural struggle can touch the soul” (quoted, Jaivin p. 28) But the cultural struggles of 1966 hurt flesh and souls. Jaivin provides brilliant cameos of the militant chaos of the Red Guards. By the end of the year some Communist Party leaders regretted the outburst of militancy. Mao embraced the chaos. At the end of the year, he praised brawling riots in Shanghai and toasted the chaos, from the safety of his residential compound, that would bring “all-out civil war and next year’s victory.”

In “Violence, Confusion and Contradiction” Jaivin describes how Mao sought to ride that chaos between 1967 and 1969. Party leaders and capitalist roaders were humiliated. But also fought back. Factions struggled for control. The Army excited and then cracked down on Red Guards and rebellions. Red Guards fought each other. Counter-revolutionaries rose up and were sent down to rural labour camps. Jaivin refers to academic estimates of excess deaths during the Cultural Revolution of between 500,000 and two million people. Many deaths occurred in this peak of chaos, with 1967 being the deadliest year. Mao’s principal internal enemy, Liu Shaoqi was purged and died in 1969.

In “The Ups and Downs of Winding Down” Jaivin describes the long, uncertain end game of the Cultural Revolution, which ended only after Mao’s death in 1976. This chapter includes the mysterious flight and death of Lin Biao, one of Mao’s major rivals, in September 1971. Amid these leadership struggles, violence and chaos, Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon showed up in Beijing. Jaivin deftly shows the narcissistic grandiosity of American versions of the “Kissinger Moment.” Nixon called the visit, “the week that changed the world.” Within China, it secured less foreign isolation, excited internal succession struggles, and goaded the radicals of the Gang of Four to the last phase of struggle. The Gang of Four included ‘Madame Mao,’ Jiang Qing who would meet a sad, tragic end. After Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong’s deaths, the cultural revolution would come to an end. The Gang of Four were arrested, tried, and became the scapegoats for the ten years of chaos.

“The new Party leadership blamed all the pain and suffering of the previous decade on this ‘Gang of Four’ - introducing Mao’s phrase to the public for the first time. People joined the campaign to denounce the four with an enthusiasm they had not showed for political movements for some years. Some, however, held up five fingers. Even if Mao had not always agreed with the Gang of Four, they could have done nothing without their chief enabler.”

(Jaivin, p. 91)

Revolutions like their scapegoats. All politics does.

Strengths of the Book

This book is like a historical novella. It condenses the complex chaotic story of the Cultural Revolution into a brief, entertaining read. But it does so without sacrificing sophisticated historical insight.

Jaivin tallies the toll of this astonishing trauma that has inspired scar literature and rebukes of ‘historical nihilism.’ 4.2 million people were detained for investigation. 1.7 million were killed, according to official statistics. The minority of these deaths (13,500) were executions of counterrevolutionaries. More (237,000) were killed in factional battles. As Danton said, the Revolution like Saturn eats its own children. Most were killed as ‘class enemies,’ guilty of thought crime, or opportunistically killed in response to undeclared grudges, resentments, and social conflicts. Millions were injured. Whole families were extinguished. The most populous country on earth was deeply traumatised.

Jaivin guides you into those shadows and shows you how to explore its depths. Do take up her invitation.

Where to Explore More

One great feature of the book is its simple clear guidance on characters, timelines and where to explore this history further.

The two-page timeline is just right to give you the arc of the story, without swamping you with detailed chronologies.

The list of main characters is indispensable. It includes party leaders, the Gang of Four, Red Guards and Rebels, other notables, and importantly prominent victims.

At the end of the book, Jaivin distils her lifetime of studying these events into a single page of recommended nonfiction, fiction, film and documentaries to explore the shadows of the Cultural Revolution more deeply.

The recommended film is indeed Farewell My Concubine. I was delighted to see that.

Jaivin’s two recommended documentaries can both be watched on YouTube. Morning Sun is directed by the Sinologist Geremie Barmé. The great Italian film director Michelangelo Antonioni also produced a 1972 documentary, Chung Kuo, in the midst of the Cultural Revolution. This documentary is available on YouTube in two parts.

Michelangelo Antonioni Chung Kuo (1972) Parts 1 and 2

Some bonus history book recommendations

A few of the books I had considered profiling for this piece were not on Jaivin’s list, including Frank Dikötter, The Cultural Revolution: A People's History, 1962—1976 and Yang Jisheng, The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. I am inclined to leave them and point you to four other books from Jaivin’s list.

Gao Yuan, Born Red: A Chronicle of the Cultural Revolution is the memoir of a Red Guard who left China in 1982. I have sampled it. It is compelling.

Three books published by Chinese authors in the last ten years are on my to-read list.

The Killing Wind: A Chinese County’s Descent into Madness During the Cultural Revolution, by Tan Hecheng (trans. Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian, 2016)

Victims of the Cultural Revolution: Testimonies of China’s Tragedy by Wang Youqin (trans Stacy Mosher, 2023)

Zhou Enlai: A Life by Chen Jian (2024).

On Wednesday, I will be exploring Klaus Mühlhahn’s interpretation of the Cultural Revolution as part of my deep dive into Making China Modern.

Coming Up in The Burning Archive

The Cultural Revolution is also covered in the book I will be recommending in next Saturday’s post, The Great Transformation: China's Road from Revolution to Reform by Chen Jian and Odd Arne Westad. But my focus there will be on the astonishing change in China’s fortunes since 1976, led initially by that witness of Kruschev’s Stalin speech, survivor of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, architect of China’s capitalist road to become the world’s largest economy, Deng Xiaoping.

If you missed it, do watch my interview with former Australian Foreign Minister Gareth Evans. And look out for my interview with KJ Noh on the Korean intercountry adoption scandal on my YouTube channel, which comes out on Saturday.

I’ll be in your in-box on Monday with the next instalment of the slow read of The Books of Jacob, looking at chapters 16 to 18. Do also check the updates to the Slow Read page with the new schedule, links to all past posts, and notes on characters.

Thanks for all the great suggestions on 100 books to read before it is too late. The dialogue with you about the writers who make us, and your recommendations from many cultures have been inspiring. I will be doing more such lists soon.

Thanks for reading

🙏❤️🌏

Jeff

Hmm…..all these Chinese history books by non Chinese scholars, or exiled Chinese. Suppose Norway was a secular socialist country (well, we are a typical Nordic social democracy), would I not be sceptical if most Norwegian history books in English were written by non Norwegians, possibly devout Christians (or of any other conviction contrary to their subject matter, say the contemporary history of socialist Norway), residing and doing research in a private capitalist, non welfare state country on another continent, i.e. a country with very different cultural reference background from that of native Norwegians. Certainly, I would be very sceptical about their methodology, their research, their ability to be fair observers of my country’s history.

I am not a scholar, but I have learned Chinese, and have lived more than twenty years in China since the late seventies. I keep looking for history books written by Chinese scholars in Chinese, and then translated into English (or any other language); not expat Chinese who moved to the US (or any other country remote from China), and then wrote history books coloured by western academia.

Thanks for information abd taking the time to reply.

It sounds like you have a lot of ground experience in China.