Decolonisation II: Mexico and the Fourth Transformation

Five centuries of history explain why Mexico will not kneel to the USA as a colony

“Therefore, it is pertinent to remember history and, in doing so, affirm that: Mexico will not return to a regime of privilege and corruption. Mexico will not return to being a colony or protectorate of anyone. And Mexico will never surrender its natural resources. Therefore, with fortitude and faithful to our history, we say forcefully: Mexico does not bend, does not kneel, does not surrender, and does not sell out! Long live the Constitution of 1917! Long live the people of Mexico! Long live Mexico!”

Claudia Sheinbaum, President of Mexico, (2026) at the 109th Anniversary of the Promulgation of the 1917 Constitution, at the Teatro de la República.

Mexico occupies a special place in the history of colonisation and decolonisation.

It illustrates the paradoxes of colonisation and the incompleteness of decolonisation.

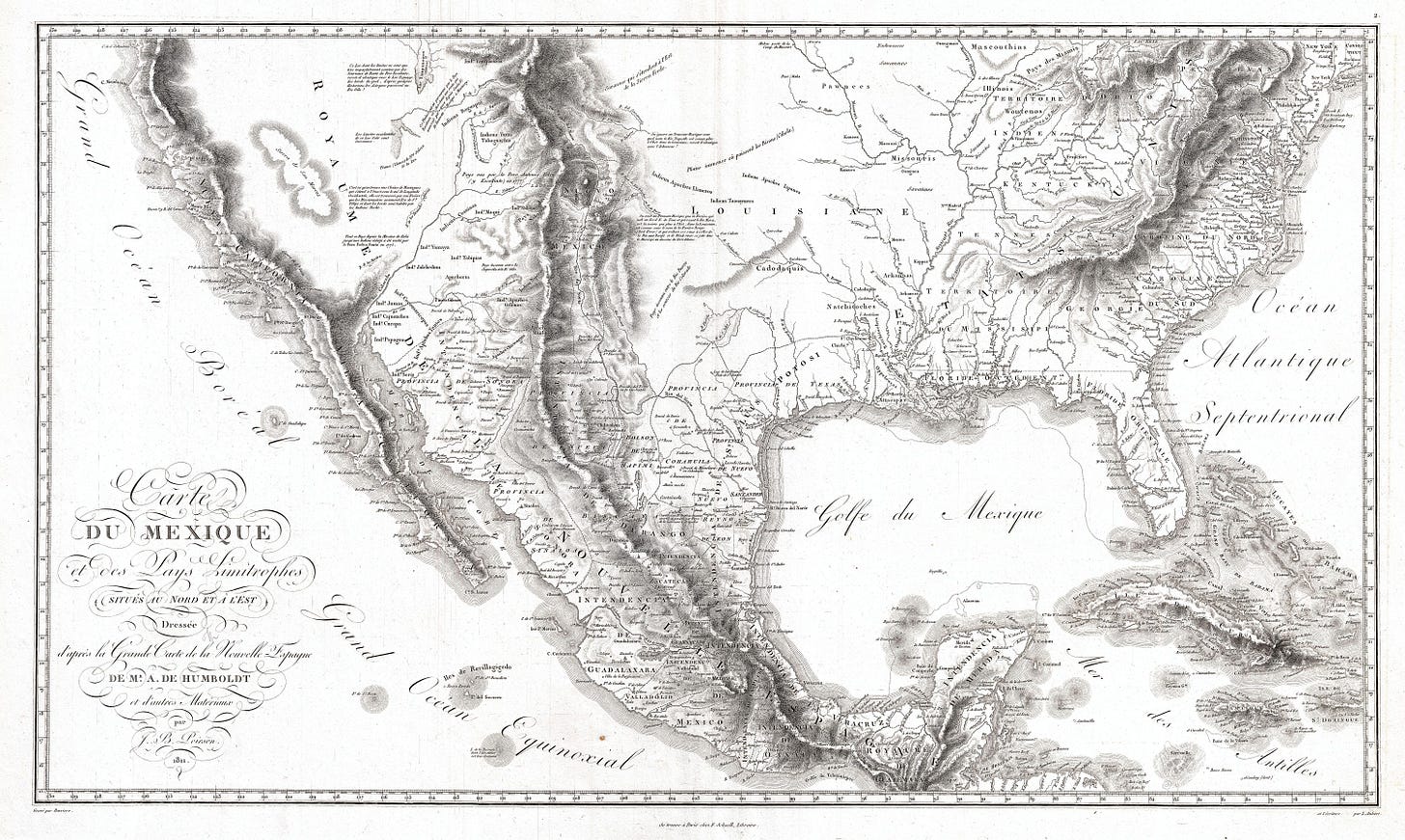

Mexico or New Spain was a principal site for the onset of “500 years of European colonialism”.

The ‘Spanish’ conquistadores, colonists and Catholics who came to the Americas and Caribbean after 1492 were the agents of a Europe-wide state led by a Flemish Habsburg prince, Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor. He was a foreigner to his own court in Madrid and yet inspired by Spanish zeal in the Reconquista, which may paradoxically be read as a centuries long process of ‘decolonisation’ (if I may stretch the term) of Muslim North African and West Asian expansion into Southern Europe. Columbus, Cortés and Pizzaro conquered the Americas in the name of this Spanish Crown, with the Reconquista and chivalric fantasies in their minds, but, in some ways, against the orders of their Emperor and the beliefs of their religion. Charles V and his successor Phillip II disciplined the wayward, ruthless, violent, greedy, crusading conquistadores as much as they lent an ear to the denunciations of their devastation of the peoples of the Americas by Bartolomé de Las Casas.

“The Spanish came like starving wolves, tigers, and lions,” wrote Las Casas in the 1550s, “and for four decades have done nothing other than commit outrages, slay, afflict, torment and destroy.” His decades of preaching did not stop the deaths by violence and disease, but his encounters with the suffering of Mexico did give birth to a first transatlantic conscience that flowed into modern day influences such as Latin American International Law (Greg Grandin, America América), modern human rights thinking, and Mexican humanism.

Colonial New Spain also developed ‘creole’ colonial societies, religions and governance that created from its people’s cruel treatment new ways to endure. Las Casas did, at times, exaggerate. The Indies were devastated, but not destroyed. Nor was Spanish violence the sole motor of the New World’s history. Their predecessor societies knew also how to slay, torment, and commit outrages in the name of religious belief. When the conquistadores came with new military technologies, the Mexica and the Inca had recently expanded violent dominion over their own known worlds. The resentments of rival local societies towards these expansionist and exploitative rulers provided a basis for collaboration between Cortés and local indigenous leaders opposed to Moctezuma. They were agents and victims, carriers of disease and converts to an adapted faith. It is one of the paradoxes of colonialism explored in Fernando Cervantes, Conquistadores: A New History (which we will read together in the History Book Club in March). But more importantly, people and their cultures survived and adapted. Though much was destroyed, enough remained. From this crucible of violence, culture and history, Our Lady of Guadalupe (Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), rose on Tepeyac Hill, Mexico City.

When the Aztec ruins of Xochicalco and the Mayan rain forest city of Palenque were discovered by archaeologists in the late eighteenth century, and combined with new European visions of enlightenment and statehood, the survival memories became a force for the first wave of American decolonisation. Inspired and emboldened by revolutionary ideas and American, European and Caribbean decolonisation from 1776, the Vice-Royalty of New Spain became between 1810 and 1821 the Mexican Empire, and then from 1824, the independent Estados Unidos Mexicanos, the United States of Mexico. In its early years, the rediscovery of the pre-colonial past became a source of post-colonial pride. Felipe Fernández-Armesto emphasised how relics of the Mesoamerican past fortified this ‘creole patriotism’:

In partial consequence, Mexicans were able to interpret their experience in terms accessible only to themselves. Their independence was a Reconquista and their state a successor to ancient glories; the first effectively independent modern Mexican state called itself an empire and its seal - with eagle surmounting a prickly pear - reproduced elements of an Aztec glyph. By comparison, in other ‘liberated’ parts of the New World, the regimes seemed prolongations of the colonial past.

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Millennium: A History of Our Last Thousand Years, (1995) pp. 339-340

Despite independence, the incompleteness of early decolonisation took only a handful of years to manifest. In 1823 the insecure ex-British colonists of the North American United States declared a Monroe Doctrine excluding European interference in their former colonies. Two years later, in 1825, this same state on the North East coast of the Americas conducted its first regime change operation in Mexico. Two decades later, the USA declared manifest destiny and seized by hook, crook and an illegal and immoral invasion, half of the territory of Mexico.

This strange defeat of the new nation of Mexico by the new empire of the USA was a great national trauma. Understandably, it led to some decades of political instability. The War of Reform (1858–1861), or Three Years’ War, was a civil war fought between Liberals and Conservatives over the 1857 Constitution. In 1861 France intervened on behalf of Mexican conservative interests, and restored a Habsburg prince, descendant of the Conquest’s emperor, Charles V, to an American throne. Archduke Maximilian of Austria served briefly as emperor of the Second Mexican Empire from April 1864 . The Monroe Doctrine was in abeyance, while the noble USA fought its own civil war over slavery. The tragic Maximilian was executed by firing squad in June 1867.

A Restored Republic ruled from 1867 but was overthrown in a coup in 1876. For the next three decades, the new leader, Porfirio Díaz, ran a model of governance, inspired by both USA investors and the European example of Napoleon III. It would become a template for Latin American Government in the twentieth century. Díaz pursued a policy of “order and progress”, inviting foreign investment in Mexico, primarily from the rapidly growing USA, and maintaining social and political order, by force if necessary. As the USA frontier closed, the Gilded Age shone, and a new colonial imperial culture took hold of the hearts and minds of both Europeans and North Americans, Mexico suffered the quandaries of a post-colonial state. Even the dictator Porfirio Díaz had no illusions about the freedom of the New World from ‘European colonialism.’ “Poor Mexico,” he quipped, “so far from God, so close to the United States.”

In 1910, Díaz was overthrown and the twentieth century’s first great social revolution began, culminating in the Constitution of 1917, whose long life Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum praised in the 2026 speech quoted at the head of this article. To my shame, I only learned of the significance of the Mexican Revolution when I read Greg Grandin’s America América. Like any revolution, it attracts many contending interpretations about origins, heroes, anti-heroes, achievements, violence, blind spots and failures. For now, let us simplify, and say the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) established a flawed social-democratic state, with a liberal democratic Constitution, agrarian reform, labour protection, and national independence from dependency on the economic neo-colonialism of the USA. It was the first great wave of decolonisation of “European empires” in the twentieth century. And this wave crashed on American shores.

While many internal social, cultural and political factors made the Mexican Revolution, one indisputable cause was the predatory and exploitative practices of US American businesses, oligarchs and state interests. The historian John Mason Hart wrote that the Mexican Revolution was the “first great third world uprising against American economic, cultural, and political expansion” (Revolutionary Mexico, 1987, p. 362, quoted Grandin). That American expansion did not congeal in a formal territorial empire, like those in Britain, France or Russia in 1917. But it was accompanied by violence, domination, expropriation of resources, and doctrines of superiority. That mix of toxins is defined by historians as different as Ferro, Veracini and Darwin, as colonialism.

Indeed, John Darwin argued the Mexican Revolution provoked a US American imperial counter-revolution. “The Mexican revolution that broke out in 1910 pushed Washington further towards an imperial mentality,” he wrote in After Tamerlane.

Events in Mexico between 1910 and 1917, therefore, stand at the source of decolonisation in the twentieth century. They are as decisive to the history of decolonisation as the end of apartheid in South Africa in 1990, or the spirit of Bandung in 1955, or Gandhi’s Salt March of 1930, or the nationalities question in the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1922. And, as in all those cases, Mexico met determined and violent resistance by the republic opposed to colonies to its north, the USA.

Mexico has made a distinctive contribution to ideas, institutions and the winding path of decolonization. It defined an agenda of social rights against the liberal, free-market imperialism of the American century. From 1917 to 1940, Mexico implemented a range of reforms to land, labour, education, and sovereign control of resource industries that became central to the practical policy agenda of decolonisation in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. As early as 1919,

“Venustiano Carranza’s Constitutionalist government in revolutionary Mexico defined social rights to human security over individual private property rights while pushing for a non-hierarchical League of Nations that respected the equal status of all member states. The unifying message was that imperialism’s denial of social and economic rights was the greatest obstacle to justice domestically and globally.

Martin Thomas, The End of Empires and A World Remade: A Global History of Decolonization, p. 60

At the 1933 World Economic Conference in London, and later, Mexico led debtor country advocacy of the interdependence of lenders and borrowers in the global financial system, and called for the need for “multilateral cooperation, currency stabilization, and international financial support from rich-world creditors.”

Mexico prioritised state control of national resource industries as a means of sovereignty and protection from exploitation by foreign investors and neo-colonial powers. In 1938, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas barred all foreign oil companies from operating in Mexico, ordered the return of the assets of most foreign oil companies to the people of Mexico, and created Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), the state-owned firm that held a monopoly over the Mexican oil industry. Ever since, nationalisation of resource industries has been the nightmare of US American and European imperial investors and the cause of countless regime change operations by USA and British intelligence agencies.

At the 1944 Bretton Woods conference and subsequently, Mexico, with other Global Majority states, argued for global economic redistribution and free trade rules to protect national industries from domination by foreign multinationals. They got some of what they wanted, even if not all, despite American titanic crowing about how the USA designed the post war economic order. The Mexican thinking on the dangers of economic dependency flowed into Latin American and post-warUN ideas of Argentine economist Raul Prebish, the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America, the Group of 77 developing country coalition and the United Nations Conference for Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

In the 1960s and early 1970s, in the heyday of decolonization, Mexican President Luis Echeverría, together with Tanzania’s Julius Nyere, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah (author of a book on Neocolonialism) and Jamaica’s Michael Manley, played a leadership role in advocating for economic sovereignty through the New International Economic Order (NIEO). Echeverría pushed and persuaded the USA, in ways not open to more radical nations or Maoist China, to provide newly independent nations with more real economic autonomy, including through a UN-endorsed Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States. Again the USA resisted, with all its contemptuous might. Thomas wrote,

Echeverría, rightly confident that the Charter would win UN General Assembly support, focussed his negotiation effort on the Nixon administration, National Security Adviser and NIEO critic Henry Kissinger in particular. The Mexican president played on Washington’s strategic interests, arguing that rejection of the Charter would be an avoidable error, bound to sharpen ideological polarization between global South nations and their rich-world creditors. Kissinger, though, was unmoved and worked assiduously to undermine the NIEO initiative.

Thomas, The End of Empires and A World Remade, p. 278

From the 1970s, the rich world fought back with a new form of neo-colonialism known as neoliberalism. And this era brought free trade, hyper-liberalism, privatisation and oligarchical free-for-alls to post-neo-colonial Mexico, especially after the end of the Cold War. To many inside and outside Mexico, it appeared that a new pro-USA, libertarian, oligarchical Mexico had bent, kneeled, surrendered, and sold out. The USA had recolonised Mexico in corporate form, stripped its assets, and exploited its people as cheap labour with limited rights in order to do the dirty work that the great US America did not want to do.

But Mexico had a century long tradition of resistance to colonialism, not just in politics and culture, but critically in its economic and social institutions. Struggles against neoliberalism and the new neo-colonialism continued, alongside endemic problems of corruption, inequalities, violence and the many curses of proximity to the USA. In 2018, after a decade of local political action, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the leader of a “popular, grassroots, and nationalist project,” Morena, won the presidency of Mexico.

Mexico began what its new Government called “The Fourth Transformation”.

The transformations evoke Mexico’s long history of unwinding colonialism. As summarised recently by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, the previous three transformations were major episodes in Mexico’s decolonising past, which I have touched on in this article and Claudia Sheinbaum commemorated in her speech.

A republic born out of violent Spanish colonisation, Mexico has traversed a long and turbulent path in search of sovereignty, social justice, and development over the last two centuries. Morena conceives of this history as one of successive transformations, namely the War of Independence (1810–1821), the War of Reform (1858–1861), and the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917). Its national project is therefore identified as a Fourth Transformation, or ‘4T’.

From Tricontinental, Mexico and the Fourth Transformation Dossier No. 92

The projects of this transformation are embedded in national economic and social development plans, cultural symbols and foreign policy. 4T’s reforms rebalance interests between social groups and national and foreign business interests, and relationships between the state and the Mexican people. Policies include ending corporate debt forgiveness, collecting evaded taxes, nationalising lithium, substantially raising wages, regulating subcontracting through the Federal Labour Law, educational reforms, drug policies, migration policies, infrastructure projects, various decolonisation initiatives, broader international engagement and challenges to the US colonial era Monroe Doctrine.

In 2024, the stated the “foreign policy of the Fourth Transformation”

“is guided by the Model of Mexican Humanism. This model puts people at the center, addressing the needs of all Mexicans, both within Mexico and abroad, in order to contribute to the construction of a more just, stable, and peaceful system.”

Mexican Foreign Secretary Alicia Bárcena 2024

Mexico sees itself as “the first country in the Global South to adopt a feminist foreign policy.” It no longer sees itself as a vassal, colony or protectorate of the USA, but as a key player in the “construction of international peace and security” with “global prestige, leadership, and relevance.” By bringing Mexican humanism to the world, a more just Mexico aims to forge a more egalitarian world.

Decolonisation in Mexico has entered a new phase, and it is unwinding a new form of colonisation. Since 2024 Claudia Sheinbaum has carried on the work of the Fourth Transformation and is negotiating new forms of real sovereignty in a highly interdependent and fractious world. Since January 2025, she has had to do so with a new imperialist in the White House. Donald Trump and many in the USA elite espouse a new expansionist, threatening form of imperial strategy, which I have dubbed regime extortion.

Regime extortion is the work of lazy mobsters who know their gang is not up to the hard work of “regime change,” responsible diplomacy or winning hearts and minds. Instead, they bully, bluff and bluster with tariffs, threats, and intimidation. They change the title of the Gulf of Mexico, at least on USA maps. They stage ‘high-visibility’ military action and even kidnap heads of state. The USA has declared a new corollary of the Monroe Doctrine, laid claims for more violent expansion, deported citizens with abrasive terror, and threatened to deploy its military forces, yet again, in Mexico’s sovereign territory. Regrettably, one cannot rule out the prospect that the USA might invade Mexico, again, like in the 1840s, in 1914, and, with its privateers, crime warlords and covert agents, from 1989.

Mexico is still the USA’s near neighbour, indeed arguably the rightful claimant to most of the USA’s South and Southwest. But it is no longer Porfirio Díaz’s “poor Mexico”, remote from God or, in secular terms, without powerful friends. A century of decolonization and at least two transformations have made Mexico into a prouder and more unyielding state. That is why Sheinbaum pointedly told Trump in her speech commemorating the Mexican Revolution that:

“Mexico will not return to being a colony or protectorate of anyone. And Mexico will never surrender its natural resources. . . Mexico does not bend, does not kneel, does not surrender, and does not sell out!”

Sheinbaum, 2026

But the violence of the US American empire is remorseless, the rapacity of its oligarchs makes kittens of the conquistadores, and the nihilistic madness of its shallow state leaves most of the world in fear of what the US American Leviathan might do next.

Mexico is very much on the frontline. It still suffers Díaz’s curse of living so close to the USA. It is, as Nel Bonilla has argued, one of the inner ring societies of the USA’s Bunker State, that perpetually insecure empire benighted by NATO’s permanent attrition war. Its frontline status threatens the life of its Fourth Transformation. As Nel Bonilla wrote this week,

the real existential threat to Mexico’s Fourth Transformation . . . is not the domestic opposition, but US imperialism. . . . Under those conditions, the Sheinbaum government’s strategy is triage under siege: hold off “the US beast” just long enough to consolidate a basic welfare state, public infrastructure, and universal healthcare before the next interventionary cycle hits.

The USA’s threat to Mexico, its people and their sovereignty should concern us all. Mexico is not just on the frontline. It is not a minor player in some great power strategic game. It is a fountainhead state of decolonisation. Its freedom is our freedom. Its fate is our fate. Its success in removing the curse of American empire will be the making of a more completely decolonised and fairer world.

Tread carefully, President Sheinbaum.

Long live Mexico!

Next week, we look at decolonisation in Africa.

Thanks for reading

🙏🌎❤️

Jeff

P.S.

Do also check out my video this week on YouTube on Europe’s declaration of independence that I have adapted from my earlier Substack post.

Why o why does my country support the US in its hateful works. Even Labour haven't protested about the USA's latest greedy gangsterism. They shame decent folk. If I was younger I'd leave this increasingly authoritarian country. Poor Mexico Indeed.

Why o why