While walking through abandoned military facilities in East Anglia, the writer W.G. Sebald, author of The Rings of Saturn, imagined himself “amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in some future catastrophe.”

Such stirrings of the imagination come to all of us today, now and then, while we scroll our phones and witness too many horrors of war that haunt our modern lives. Who today — amidst news reports of world leaders playing a dangerous game of brinkmanship with nuclear powers — does not occasionally have intimations of our own civilization’s mortality? We do not need to walk among military facilities to know the power of destruction, but can glance through any social media stream at bombed children, ruined cities, and deceitful leaders urging others to fight, and to die, for their ambition.

Yet to look intently at the ruins of war and the horror of that destruction is difficult, exhausting and depressing. If you have even a partial knowledge of the history of humanity, you realise that the records of such destruction stretch back so long, so deep and so wide that you cannot readily imagine escaping that ultimate catastrophe Sebald saw amidst military ruins in East Anglia.

Sebald, The Rings of Saturn is a book that has supported me to witness the horrors of history for decades now. Over the last fortnight, I re-read this strange, hybrid, mesmerising book. It was a conscious decision to seek, in the beauty of this meditation on the ruins wrought by history, some way of enduring and thriving despite so many intimations of catastrophe.

The author of this book was Winfried Georg Sebald (1944 – 2001). He was a German writer and academic who had moved to Britain in young adulthood. He preferred to use the first name of Max, and this decision was in part the rejection of his family heritage, which was tainted by participation in the Nazi regime of Germany and willing blindness to the Holocaust.

In his late teens, Sebald broke with his father, who had served in the Wehrmacht under the Nazis and was a prisoner of war until 1947. In the years after the war his father and family, and many fellow Germans and Europeans, did not face the trauma, guilt and horror provoked by the events which they participated in and witnessed from the 1920s to the 1940s. Sebald, however, refused to blind himself, either to the horrors of the Holocaust or to the destruction wrought on Germany by the Allies. The ruins of German cities and the losses of so many Germans, at least some of whom were ‘innocent civilians’ and not party to the Nazi crimes, haunted a generation of German citizens, leaders, writers and intellectuals. How could they speak of German loss, trauma and suffering, when Germany, or its leaders and allies, had perpetrated such war crimes? What redemption was there after participation, or complicity or negligence, in such horrors? As Adorno wrote, there can be no poetry after the Holocaust. Yet, on the other hand, how could they not speak of the traumas they had known when orphans and neglected children roamed across the rubble of their cities; when everyone knew someone who had been killed, maimed, raped, persecuted or tortured?

Sebald’s father and family retreated into silence. So too did many Germans, and many more or less guilty followers in other nations. But Sebald himself, from his school years, refused to do so. While at school, he was shown films and photographs of the Holocaust. He sought explanations from teachers, his family and the witnesses of this horror, but no one spoke to him honestly, and no one knew how to explain what they had just seen. Nor did anyone speak frankly about the mass destruction by bombing raids of British and American allied forces, consciously planned by ‘Bomber’ Harris to terrorise the civilian population. These raids on 131 German cities killed 600,000 German civilians and destroyed 3,500,000 homes. In instants, whole cities were incinerated, such as in the fire-bombing of Dresden, or, in Germany’s ally Japan, of Tokyo. The destruction would culminate in the atomic bombs dropped by the USA on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Sebald wrote much later, in On the Natural History of Destruction,

“The darkest aspects of the final act of destruction, as experienced by the great majority of the German population, remained under a kind of taboo like a shameful family secret, a secret that perhaps could not even be privately acknowledged.”

These themes of the destruction and cruelty that reached their pinnacle in the Holocaust, but are enacted in many other ways in past and modern civilizations, especially through warfare, persecution, and exploitation of nature, became central to Sebald’s writing. He would write as a wandering alien from his country, and an exiled citizen from his culture. These themes lay at the enigmatic, secret heart of the strange book, The Rings of Saturn.

It is a book of haunting beauty, and extraordinary untimely prose, which are reasons why I return, again and again, to this book for consolation, amidst the horrors and ruins of our times. It has been variously classified as novel, fiction, essay, memoir, travelogue, creative non-fiction or simply writing. Michael Hamburger, the poet and translator, who appears in disguised form in the book, offered the best description of its form. It was, he said, an “essayistic semi-fiction which gives rope to both observation and imagination.’

This essayistic semi-fiction is also a form of history, and a deep reflection on the difficulties of recovering, remembering and writing about the past. Faintly evoking Walter Benjamin’s famed fable of the Angel of History, her face turned in tears to the past as the storm of progress blows her fast to the future, Sebald reflected frequently in The Rings of Saturn on the puzzling difficulty of remembering the past.

“This then, I thought, as I looked round about me, is the representation of history. It requires a falsification of perspective. We, the survivors, see everything from above, see everything at once, and still we do not know how it was.”

W.G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn

The book has, therefore, always been an important work in the Burning Archive. It is a book that set a course for my writing; after falling under Sebald’s spell, I resolved to write semi-historical essays, not fiction, not academic history. His manner of associative digressions and his style of retrieved pre-modernist elegance have informed how I write, or at least aspire to write. It may be evident in this Substack and certainly in some of the essays in From the Burning Archive and Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Bureaucrat.

The Rings of Saturn is also a book that honours by following the unique paths of strange and remarkable writers. In the first three pages of the book we meet Kafka. Along the way we meet the translator of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Swinburne, Chateaubriand and Joseph Conrad. However, much of the book is a tribute to one great English essayist, who was buried in Norwich as told by Sebald in The Rings of Saturn, and whose skull is one focus of the first mesmerising chapter of the book.

That writer is Sir Thomas Browne (1605 - 1682), an English doctor, who practised in Norwich, and essayist, who, Sebald says as a disciple of his famously elaborate prose, “left a number of writings that defy all comparisons.” Browne practiced medicine in an era transitioning from Renaissance to Enlightenment, but which knew much abominable darkness. The seventeenth century was a period of rolling global crises, which, some argue, were connected to changes in weather patterns (see Geoffrey parker, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century). It was a period of religious and civil wars across Europe, including Russia, which included the Thirty Years War, the Time of Troubles (Smuta) and the overthrow of the Ming in China. In Britain, it was the era of the English Civil War, and Cromwell’s brutal Puritanical Commonwealth. The English Civil War bled hundreds of thousands of victims, a few of whom Browne sought to heal, and hundreds of ideological zealots, from whom Browne, kept his distance. He reflected on the religious and ideological disputes of a Britain that had descended into Devil-Land (see Clare Jackson, Devil-Land: England Under Siege, 1588-1688 (2022) in his essay Religio Medici (A Doctor’s Religion):

“I could never divide my selfe from any man upon the difference of an opinion, or be angry with his judgement for not agreeing with mee in that, from which perhaps within a few days I should dissent my selfe...”

Thomas Browne, Religio Medici

Sebald returns throughout the book to this articulate and compassionate witness of the destructive horrors of a world in crisis. But, although on the surface the book reads as the memoir of a walking tour in East Anglia, he draws in many other testimonies to cruelty and compassion in history. We read of the brutal destruction of Beijing by English forces in the nineteenth century, and the cold cruelty of the last Chinese Dowager Empress. We read of Joseph Conrad’s experiences in the Congo that led to the creation of the character, Kurtz, who in his death scene in Heart of Darkness, speaks like a ghost of the horror, the horror. Yet, we also learn of the compassionate Roger Casement, who exposed so much colonial cruelty in Africa, the Americas, and in Ireland. The British Government, however, rewarded this courageous early humanitarian with a cruel, punishing execution that sought to extinguish all memory of his goodness.

The Rings of Saturn is a book about the ruins and incoherent fragments of the past that haunt the present. It emerged from a period of severe depression for the author, Sebald, which is evoked at the start of the book.

In August 1991, when the dog days were drawing to an end, I set off to walk the county of Suffolk, in the hope of dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work…. I wonder now, however, whether there might be something in the old superstition that certain ailments of the spirit and of the body are particularly likely to beset us under the sign of the Dog Star. At all events, in retrospect I became preoccupied not only with the unaccustomed sense of freedom but also with the paralysing horror that had come over me at various times when confronted with the traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident even in that remote place.

Sebald, The Rings of Saturn

But it is a book that transcends a personal response to depression, and celebrates with melancholy the obsessive creativity of humanity in the face of our fellow human destructiveness. It does not shy away from our common impotence before our all-too-human cruelty.

This spirit makes The Rings of Saturn a book for our times. As we witness, with renewed horror and frightening weakness, the tragic killing in Gaza, Ukraine, Yemen and other bloodlands of the world. The generations who live today may share something with the post-1945 generations of Germany, some of whom, like Sebald knew a profound alienation from the complicity of our leaders in perpetrating horrors, and yet sought to rescue from the rubble of the fragile cultures that was falling around them something to leave behind that was beyond all comparisons.

Perhaps even Thomas Browne, who wrote four centuries ago, has some wise advice for us, we, sad witnesses of another tragic year.

“Where life is more terrible than death, it is then the truest valour to dare to live.” Thomas Browne

If you would like to explore Max Sebald further you may buy it here at this affiliate link The Rings of Saturn. I have also recorded my reading of the first chapter of Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn that I will post on my YouTube channel next Saturday.

There is also an intriguing and evocative British documentary about Sebald and The Rings of Saturn that can be viewed here and on several other YouTube channels.

Until my next post, take care, dare to live, and even share the Burning Archive with a friend.

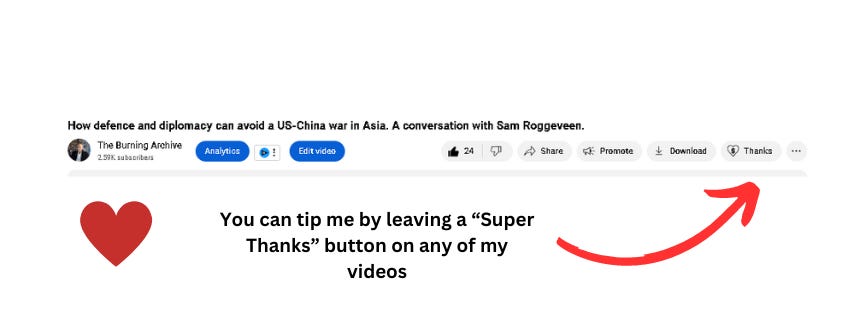

P.S. A few readers have suggested that I set up a tip jar, and I am in the process of doing so. If you want to support my writing and content creation, but are wary of contracts and ongoing subscriptions, then, until that Tip Jar is set up, you can give me a Super Thanks on any of the videos on my YouTube channel. See my little diagram below.

willing blindness to the Holocaust? Consider this

• For almost three years German trains, operating on a continental scale, in densely civilized regions of Europe, were regularly and systematically moving millions of Jews to their deaths, and nobody noticed?

• Even those few Jewish leaders making public ‘extermination’ claims were not acting as though it was happening.

• Ordinary communications between the occupied and neutral countries were open, and they were in contact with the Jews whom the Germans were deporting, who thus could not have been in ignorance of "extermination" if those claims had any validity.

• What ‘evidence’ we have was gathered after the war, almost all oral testimony and ‘confessions,’ otherwise, there would be no significant evidence of "extermination."

• Yet this three-year program, of continental scope, claiming millions of victims, required court trials to argue its reality.

• Thus, the Jews were allegedly gassed with a pesticide, Zyklon, and their corpses disappeared into the crematories along with the deaths from ‘ordinary’ causes (neither ashes nor other remains of millions of victims having ever been found).