Forgotten, Famous and Favourite Nobel Literature Prize Winners, 1968 to 1974

Under pressure from the past: Kawabata, Beckett, Solzhenitsyn, Neruda, Böll & White

The Nobel Prize for Literature between 1968 and 1974 went to some of the twentieth century’s most famous writers: Beckett, Neruda, and Solzhenitsyn. These writers made sense of the pressures of the past from the terrible century they had witnessed. Those pressures made for great writing and many sorrows.

The eight winners in this period included:

The first Asian writer to win the Prize since 1913

Supporters and opponents of Stalinism, decolonisation, and dissent

Stories of scandal, sorrow, suicide, and remembrance of the wrongs of war.

Please join me as I read all 120 writers who have won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Some are forgotten. Many remain famous. A few became notorious for reasons that might surprise you and change your understanding of modern history. Discover them all in the 120 Nobels Challenge and let me know your favourites.

This week, we read the winners from 1968 to 1974:

1968 Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972) Japan

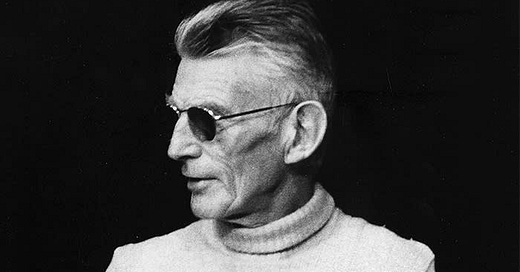

1969 Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) Ireland/France

1970 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) Soviet Union/Russia

1971 Pablo Neruda (1904–1973) Chile

1972 Heinrich Böll (1917–1985) Germany

1973 Patrick White (1912–1990) Australia

1974 Eyvind Johnson (1900–1976) Sweden (1 of 2)

1974 Harry Martinson (1904–1978) Sweden (2 of 2)

Voiceover is available if you want to listen on a walk.

Be sure to read to the end of this post where you will find links to bonus archival video footage of these Nobel Laureates. Or watch my YouTube channel after 8 pm Sunday (AEST).

1968 Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972) Japan

Kawabata was a Japanese novelist and short story writer, who wrote within Japanese literary traditions. He was the second Asian writer to win the Prize, but fifty-five years after Tagore won in 1913. The young Kawabata had indeed read Tagore who had lectured on nationalism in Japan.

Kawabata was the first Japanese writer to win the Prize and his award was part of the reintegration of Japan into the Western cultural domain after the Great Imperial War of 1931-1945 (Second World War). Kawabata had played a major role in cultural diplomacy after the war. He had attended the Japanese war crime trials and visited the scene of unacknowledged US war crimes at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was the President of PEN in Japan and organised several major peace and literature conferences, including in Hiroshima, in the 1950s and 1960s. Together with the Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964, his cultural diplomacy helped reconcile the West to Japan and support the Swedish Academy to acclaim literature outside the charmed Atlantic circle.

The Nobel Committee framed Kawabata’s writing in vaguely orientalist terms as similar to haiku and Japanese painting traditions. Kawabata was no Western writer, although he had learned from Dostoevsky and modernists. His writing was, however, influenced by the rich variety of Japanese literary tradition, stretching back to the first acknowledged “novels” of around the year 1000 - Murasaki Shikibu, Tale of Genji, and the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagan. He studied these works of the Heian period (794 to 1185, Heian means peace) in his youth. Their language and techniques are demanding even for modern Japanese, just as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in middle English are for modern readers. He also adopted their aesthetics of imperfection and incompletion, leaving many of his works unfinished or constantly reworking them. His Nobel lecture referred to this Zen Buddhist aesthetic of Japanese culture, and noted:

“The heart of the ink painting is in space, abbreviation, what is left undrawn."

During the war, and the fire-bombing of Tokyo, he turned to Tale of Genji, and reread it often with the intent to protect its values from the flames. He came to see himself as a vessel to preserve the traditions of the past amidst the destruction of the war. In 1944, he compiled writings of Japanese who had died in the war. After the war and the American military governorship of Japan (1945-1952), Kawabata’s writing was scarred by grief for the loss of Japanese culture, traditions, and style. One critic wrote that he mourned the lost Japan, and “sensed within the defeated people of Japan the same orphaned condition that had been his own in the past.”

Both his parents had died when Kawabata was young. He was raised by his blind grandfather. His grief was deepened again at the age of sixteen when this only carer died. He felt tormented by his “orphan’s disposition.” These scars were ripped open in his twenties when a 15-year-old girl rejected his marriage proposal. In response to these traumas, Kawabata developed the habit of staring blankly into the faces of his companions. Despite many literary activities, he was a recluse. From the 1950s, he developed an addiction to barbiturate sleeping pills. His orphaned condition ultimately overwhelmed him.

His grief led his fiction to brood on the unbridgeable distance between people. It was not only a personal obsession. His theme echoed classics of Japanese and Buddhist literature texts. But Kawabata shaped this classic idea into modern, spare, subtle narratives. They treasured the Japanese past, but with a sense of detachment. The distance between the present and the past could not be bridged, nor, in Kawabata’s experience, could the separation between people.

His major works include Snow Country, Master of Go, Thousand Cranes, Beauty and Sadness, and The Sound of the Mountain. They narrate stories as loosely connected images. This narrative approach both disregarded Western traditions and emulated Western modernists. For Kawabata they were an adaptation of the Japanese poetic or literary tradition of renga, linked verse that connects images from the closing and next verse.

I have been reading Snow Country this week. It presents the story of an affair ruined by emotional distance. Shimamura, the man, is a Tokyo student of Western ballet who refuses to spoil his admiration for the art form by watching it. Komako, the woman, is a geisha in a remote hot-spring town in the ‘snow country’ of Japan’s north-west mountains. Their affair is complicated by a second woman, Yoko, whose tragedy ends the story.

She lay unconscious. For some reason Shimamura did not see death in the still form. He felt rather that Yoko had undergone some shift, some metamorphosis…

Shimamura felt a rising in his chest again as the memory came to him of the night he had been on his way to visit Komako, and he had seen that mountain light shine in Yoko’s face. The years and months with Komako seemed to be lighted up in that instant; and there, he knew, was the anguish.

Snow Country p.174.

The 15-year-old woman who had spurned Kawabata was from the Snow Country. The tale he rewrote constantly from the 1930s is considered his mid-life masterpiece. The Sound of the Mountain is considered the best work of his later life, so scarred by grief. It presents a wise, wounded man who approaches death and seeks solace in the traditions that he has loved best.

After the Nobel Prize one last tragedy broke Kawabata. Since the 1930s he had acted as a mentor to Yukio Mishima, the Japanese novelist. In November 1970, Mishima committed seppuku. The loss of his most treasured protege sent Kawabata into inconsolable, unremitting grief. In 1972 Kawabata died by gassing in his apartment. His friends claimed it was an accident. There was no note, no ritual like Mishima. But it is likely he ended his linked verse there and then.

1969 Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), Ireland/France

From my teenage years I remember a television documentary on Samuel Beckett. An Irish voice, set against the lapping of the Liffey and sad music, read the line from The Unnameable.

“Keep going. Going on. Call that going. Call that on.”

It was quintessential Beckett, like his often quoted line from Worstward Ho,

"Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

This last line has become a meme for optimistic self-help guides and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. It is a paradoxical fate for Beckett’s writing. He saw his writing as the only compensation for the ruin, despair, and mess of his life. But writers have no control of the reception of their works.

Beckett considered his prose works his most important work. These works include the trilogy of absurd, isolated narrators, Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnameable. I have dipped into this trilogy over decades. That line I heard as a teenager, I adopted as one of my own mottos for life. But I have never read them all from start to finish, unlike his short texts, which he called “fizzles”, and his well-known plays.

Waiting for Godot may be the most famous play title of the twentieth century. But Beckett himself considered it to be a bad play. He wrote it to blow off steam after the difficulties of German occupation in France, his complex relationship with James Joyce and his schizophrenic daughter, and the struggle to fail better in his prose. Beckett said that he “began to write Godot as a relaxation, to get away from the awful prose I was writing at the time” (Deirdre Bair Samuel Beckett: a biography, p. 381)

It was written in French in 1948-49 and first staged in Paris in 1953. Beckett adapted the text in response to feedback from actors and the theatre director over the next twelve years, before publishing a definitive edition in 1965. The play about two tramps waiting for someone who never arrives became a spectacular success. It made Beckett into a playwright, not just a tortured novelist. He went on to write other innovative dramas, like Krapp’s Last Tape.

But Waiting for Godot’s fame overshadowed his prose works and annoyed Beckett. Everyone wanted to know who Godot was and whether he represented the death of God, if not also the death of the author. Literary sleuths searched for prior usage of the name. All sorts of theories were invented. Beckett himself spread stories of the meaning of the title to frustrate the sleuths. His most common story was that he had used an adaptation of the French slang word for boot (gidillot, godasse).

Why did this unlikely absurdist play become a household name? In part, it was the language. Beckett broke with the dead traditions of European theatre. According to his biographer, Beckett was the first postwar playwright to write dialogue in everyday spoken French. In part, it was the humour. The play has many funny lines reminiscent of vaudeville comedy. Moreover, the play’s black humour on existential questions captured the spirit of the age. Deirdre Bair wrote that:

“When it was produced, Europe was caught up in what have come to be political clichés: Iron Curtain, cold war, social unrest, political upheaval, the nuclear age. Existentialism held sway in France and had attracted followers around the world. The older, cultivated and mannered literature no longer satisfied. Drawing-room comedies seemed jaded, as did the literature of the other extreme, Surrealism. Readers and audiences were hungry for something new with which to express the condition into which humanity had tumbled. In the simplicity of Waiting for Godot, they found the complexity of the human condition.

(Deirdre Bair Samuel Beckett: a biography, p. 389)

Like Kawabata, Beckett wrote in grief for the loss of his pre-war world of culture. Bair wrote, “The Paris he had known and loved in 1939 could never be resurrected. He accepted the change, but was saddened by it.”

Beckett foregrounded a speaking voice without body, without character, and endlessly preoccupied with the limitations and weaknesses of its broken Cartesian self. French criticism and philosophy after the war would take up the theme. Roland Barthes proclaimed the death of the author. Robbe-Grillet and others wrote the emotionless nouveau roman. Michel Foucault turned to Beckett in his 1969 essay, “What is an Author?” It challenged the cult of the author, central to the Nobel Prize, as the ideological baggage of “the privileged moment of individualization in the history of ideas.” Foucault continued:

Beckett nicely formulates the theme with which I would like to begin: “What does it matter who is speaking’ someone said, ‘what does it matter who is speaking’.” In this indifference appears one of the fundamental ethical principles of contemporary writing.”

Foucault Reader, p. 101

Foucault misread his man. Beckett was deeply concerned with individualisation. His dramas of narrated selves are like cinemas of fragments and complexes of his selves that the writing tries to stitch together. The stories call that self ‘going’, and that purpose ‘on’. Beckett was deeply influenced by the great psychologist of individuation, Carl Jung, and wrote his fiction and plays as a psychodramatic confrontation with the fragments and complexes he found in his deep introspection.

So ‘who spoke’ did matter to Beckett, even if he always doubted his own voice. But what mattered most to this writer was that the show of the self must go on, even if it was a failure. His biographer wrote that of all twentieth century writers Beckett’s life was most consumed by writing and not external events. Beckett said his own life was “dull and without interest”. What mattered was that someone was speaking and writing:

“Nothing matters but the writing. There has been nothing else worthwhile. …I couldn’t have done it otherwise. Gone on, I mean. I could not have gone through the awful wretched mess of life without having left a stain upon the silence.”

Samuel Beckett

1970 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) Soviet Union/Russia

From my shelf I take down my three surviving books by Solzhenitsyn: One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Cancer Ward, and The Gulag Archipelago. From my memory, I draw down the stories of Stalinist Russia that I read in First Circle, a book that somehow I lost.

It was First Circle, and its fact-fictional portrait of Stalin, that I recall writing about in my first-year university history exam. In 1981, I was an aspiring history student who had begun his long engagement with Russian culture. Solzhenitsyn was then an exiled Russian writer. Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov, who had expelled the dissident writer, still ruled the Soviet Union. Solzhenitsyn's dissent from both the Soviet Union and the West had reached my island home in the South Pacific.

He was a controversial figure. His portraits of Soviet repression, including his own life as a prisoner in the Gulag, were suppressed by the Soviet leadership, embraced by the Western Right, and resisted for a long time by the diehard Western left. When I read Solzhenitsyn in the late 1970s, many leftist friends thought he was a crazy Russian Orthodox nationalist. The Gulag Archipelago, however, had shaken the foundation of faith of the Western Left, especially in Europe. Even so many socialists despised his belief in religious faith.

Left or right, his Western backers were surprised at his denunciations of the spiritual bankruptcy of the American century. They would become even more distant when after the dissolution of the Soviet Union he returned to Russia, denounced NATO's eastward expansion towards Russia's borders, and described the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as "cruel." The Western leaders who had embraced Solzhenitsyn as an exiled critic of the communist evil empire had not expected the prophet to attack them as "aggressors" who "kicked aside the UN, opening a new era where might is right." Conservative cultural warriors today, like Jordan Peterson and Rod Dreher, lionise Solzhenitsyn’s refusal to live in lies, but dare not acknowledge the truth that their hero Solzhenitsyn argued, in similar terms to Vladimir Putin, that Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus were a triune nation of brotherly Slavic Orthodox cultures.

They should have learned from his famous Harvard commencement lecture that Solzhenitsyn represented a pre-Communist, conservative tradition of Russian thought that rejected the liberal West as strongly as it did the atheist Marxists. In that 1978 lecture, ‘A World Split Apart,’ which you can read and watch here, he wrote

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today. The Western world has lost its civic courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, in each government, in each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations. Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of a loss of courage by the entire society.

But he was harsher still on the ideology of the Soviet Union. His writings about the Gulag were contentious, but they expressed common memory. His attacks on the moral emptiness of Communism were more challenging. He attacked Stalinism, but had no truck with the common belief, including among a large share of Western leftists, that Stalin was a malformation, and Lenin was the true revolutionary. What could have been had Vladimir not had that stroke in 1922. His 1975 pamphlet on Lenin tore apart the legend that Lenin was a kind, humane man. It distressed the Politburo, even Gorbachev. The image of Lenin as revolutionary saint was common until 1989, among the late Soviet leadership, and many left-wing Western intellectuals. Solzhenitsyn exposed Lenin as a monster, and history tends to agree.

His novels are profoundly observed wisdom. I recommend reading the short One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, and my lost First Circle. They were all the product to some degree of the Kruschev thaw from the mid 1950s to the 1960s. Their repression came from the Brezhnev freeze after 1966. They remind us that Soviet culture was not uniform, not its history monotonic.

The Gulag Archipelago is more contentious. It is a blend of fact and fiction, document and invention. It is the gospel truth, according to Jordan Peterson and Anne Applebaum. Its good words were amplified by the conservative culture warrior, Robert Conquest. But many Russians and historians question its veracity and reliability. It presents the purges and the prisons as the most extreme version of the amorality of Marxist vision, without any real historical explanation. Its recent adoption by conservative culture warriors misrepresents Gulag’s place in Russian cultural life. In 1989 it was serialised and freed from censorship. But so too were many repressed books: Orwell’s Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Grossman’s Life and Fate, Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, And Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem. It was a sensation in the glasnost era but is not the only version of Soviet life in Russia today.

When Solzhenitsyn received the Nobel Prize, he was still a citizen of the Soviet Union. He had spent two decades railing against censorship, and participating in the powerful subculture of the intelligentsia who distributed hand-written samizdat that Czech dissidents would call the Parallel Polis. He struggled not only against the political leaders but also the powerful writers established in comfort in the Union of Soviet Writers. Those authors operated and gained from a closed media system. When Solzhenitsyn addressed the Harvard graduates in 1978, he shocked the power elite by drawing comparisons between this corrupt system and the press in the West.

Hastiness and superficiality—these are the psychic diseases of the twentieth century and more than anywhere else this is manifested in the press. In-depth analysis of a problem is anathema to the press; it is contrary to its nature. The press merely picks out sensational formulas.

Such as it is, however, the press has become the greatest power within the Western countries, exceeding that of the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. Yet one would like to ask: According to what law has it been elected and to whom is it responsible? In the Communist East, a journalist is frankly appointed as a state official. But who has voted Western journalists into their positions of power, for how long a time, and with what prerogatives?

There is yet another surprise for someone coming from the totalitarian East with its rigorously unified press: One discovers a common trend of preferences within the Western press as a whole (the spirit of the time), generally accepted patterns of judgment, and maybe common corporate interests, the sum effect being not competition but unification. Unrestrained freedom exists for the press, but not for the readership, because newspapers mostly transmit in a forceful and emphatic way those opinions which do not too openly contradict their own and that general trend.

Nearly fifty years later, it is among his most prescient of prophecies.

1971 Pablo Neruda (1904–1973) Chile

Pablo Neruda was a Chilean poet, diplomat and politician. One reader nominated him as their favourite writer-diplomat. But some who knew him distrusted his character. The greatest Latin American writer who did not win the Nobel Prize, Jose Luis Borges said of Neruda:

"I think of him as a very fine poet, a very fine poet. I don't admire him as a man; I think of him as a very mean man."

—Jose Luis Borges

To this day he has fervent admirers and determined haters.

Neruda’s lush lyrics of passion never resonated with me, though I have given them another try this week. I never really knew why he was so famous, or why Borges would say what he did, until in researching his story this week I discovered our old friends, Stalin, the CIA, and sexual abuse.

Neruda was a gifted poet from a young age. He wrote surrealist poems, historical epics, political manifestos, a prose autobiography, and the love poems for which he is famous. He became known as the national poet of Chile. The great critic, Harold Bloom went further. He admitted him into The Western Canon. For Bloom, Neruda was a Latin successor to Walt Whitman, who he adored and I never much liked. Bloom regarded “The Heights of Macchu Picchu” from Canto general to be the best work to introduce Neruda to readers like me who do not know Spanish.

Here is the first verse of this sequence of twelve chants in English and Spanish:

From air to air, like an empty net,

I went wandering between the streets and the

Atmosphere, arriving and saying goodbye,

Leaving behind in autumn’s advent the coin extended

From the leaves, and between Spring and the wheat,

That which the greatest love, as within a falling glove,

Hands over to us like a large moon.

Del aire al aire, como un red vacía,

Iba you entre las calles y la atmósfera, llegando y despidiendo,

En el advenimiento del otoño la moneda extendida

De las hojas, y enre la primavera y las espigas,

Lo que el más grande amor, como dentro de un guante

Que cae, nos entrega como una larga luna

The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems ed Mark Eisner 2004

Another poem from Canto general (1950) introduces Neruda’s deep political commitments. It is titled, “The United Fruit Company”, the same American business we met in the post on Asturias (1967), exploiting the people of Guatemala.

The United Fruit Co.

When the trumpet sounded, everything

On earth was prepared

And Jehovah distributed the world

to Coca Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, and other entities:

The Fruit Company Inc.

Reserved the juiciest for itself,

The central coast of my land,

The sweet waist of America.

It rebaptized the lands

“Banana Republics”

And on the sleeping dead,

On the restless heroes

Who’d conquered greatness,

Liberty and flags,

It founded a comic opera.”

The “learned flies adept at tyranny” unleashed by the Fruit Co. might have collaborated with American Greatness, but not Neruda. Neruda was a proud Communist. His early career as a diplomat in 1930s Spain included "the noblest mission I have ever undertaken" transporting 2,000 Spanish refugees from Franco's regime, who had been housed by the French in squalid camps, to Chile and safety from the Nazis. He saw and admired the heroism of the Soviet Union under the assault of Nazi Germany and the old European empires. He wrote songs in praise of the Battle of Stalingrad. He celebrated Stalin, Lenin, and other leaders of the international revolutionary movement. In the late 1940s and 1950s, Communism, Marxism or Socialism were at the vanguard of opposition to the colonial North Atlantic powers. Though a “distasteful excrudescence” for Harold Bloom, Neruda’s communism was central to his poetic identity and rebellion against new imperialism.

It led him in 1948 to be exiled from Chile by a pro-US regime. He was later elected as a politician in Chile and was mooted as a candidate for President. He deferred, however, to the Socialist candidate, Salvador Allende, who in 1970 became the first Marxist to be elected president in a liberal democracy in Latin America.

Neruda became his close supporter and adviser. But his old enemies, the ‘learned flies adept at tyranny”, unleashed by the United Fruit Co. and the CIA, were not pleased with the outcome of these free and fair elections. The dark prince Kissinger instructed the intelligence agencies that Allende had to go. In 1973 American agents assassinated Salvador Allende.

They did not stop there. A brief time later Neruda fell strangely ill following a hospital visit and died. The word on the street was the CIA had killed the poet who had defied them. The murders ushered in a dark time for Chile, the rule of the USA-sponsored military dictatorship of August Pinochet.

Many years later, in 2015, after years of national reconciliation for the crimes and murders of the Pinochet regime, the Chilean government stated its official position that "it was clearly possible and highly likely" that Neruda was killed as a result of "the intervention of third parties." The Americans object still and muddy the waters with tests. As we all know, the American intelligence agencies never lie.

Neruda’s poetry was lyrical. His political life was a heroic tragedy. But there were reasons Borges thought he was a mean man. In the 1930s he fathered a disabled child with one of his many lovers. The child was repudiated, mocked, and abandoned by her father and later died in complete poverty in Nazi-occupied Netherlands. In 2018, during the me-too movement, controversy erupted about the Chilean national poet whose writings described lyrically his rape of a Sri Lankan maid.

Pity the country, even the republic of letters, in need of heroes.

You can read more of Neruda’s poems and a more in-depth profile here.

1972 Heinrich Böll (1917–1985), Germany

Heinrich Böll was awarded the prize "for his writing which through its combination of a broad perspective on his time and a sensitive skill in characterization has contributed to a renewal of German literature."

He was the first German citizen to win the Prize since 1945. It came in the year Munich hosted the Olympic Games and reflected international forgiveness for Germany after World War Two.

Böll had refused to join the Hitler Youth during the 1930s but was conscripted into the Wehrmacht. He served in Poland, France, Romania, Hungary, and the Soviet Union. During his war service, Böll was wounded four times, contracted typhoid, was captured by US Army soldiers in April 1945, and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp.

After the war, Böll became a full-time, prolific, and successful writer. From the early 1950s, his fiction portrayed the post-war generations struggling in their new social environment of war, terrorism (including the left terrorism of the Baader-Meinhof gang), political divisions, and social change. Eccentric individuals opposed clumsy authorities. Deep undertones ran through the ironic prose. Böll was committed to pacifism. Like many of his generation, he was determined that Germany should never again do what it had done. His prose challenged Germans, especially those in authority, to come to terms with the errors of their past.

Some called him the “conscience of the nation” for his commitment to the post-war German practice of Vergangenheitsbewältigung or "struggle of overcoming the past" or "work of coping with the past." But Böll disliked the label. To examine their conscience after the war was every German’s moral obligation. Many conservatives disliked the prick of conscience that Böll provoked. Others grouped his work with a generation of writers under the rubric of the literature of the rubble, which dealt with the physical, emotional, and cultural ruins left behind in Germany after the war. He makes an interesting comparison to the later W.G. Sebald whose prose I know better.

Sebald wrote of the silence into which many Germans fell, traumatised by their own conscience, after 1945. in On the Natural History of Destruction,

The darkest aspects of the final act of destruction, as experienced by the great majority of the German population, remained under a kind of taboo like a shameful family secret, a secret that perhaps could not even be privately acknowledged.”

Böll wrote similarly in The Train Was on Time

“But the silence of those who said nothing, nothing at all, was terrible. It was the silence of those who knew they were all done for.”

I have read only one of Böll’s many works, The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1974). It presents a narrative like an investigative report dealing with the case of Katharina Blum. She is an innocent housekeeper whose life is ruined by a reporter and a police investigation following her lover’s involvement in a bank robbery. The villain of the story is tabloid journalism, modelled on Germany’s major daily Bild-Zeitung. The narrative unfolds in a mood of social panic over the many incidents of Red Army Faction terrorism in the 1970s in Western Germany. It is short, compelling, and worth a reread.

There is a guide to his works in German, which you can auto-translate, here. On the wider topic of the history of Germany and how it was affected by the war, you may like to read my posts on the German problem and Sebald’s reflections on the history of destruction and the literature of the rubble.

1973 Patrick White (1912–1990) Australia

Patrick White was the first, and as yet only, Australian writer to win the Nobel Prize. The committee honoured him “for an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature.”

White introduced this Great Southern Land “into literature” only from a certain perspective of remembering cultural history. The claim betrayed the Eurocentric or Western Atlantic mindset of the Swedish Academy in 1973, and perhaps even of Patrick White himself.

White was ambivalently Australian. He was born in Britain to a wealthy family who moved back and forward between the imperial metropolis of London and the colonies. White followed a similar pattern in his own life, settling in Australia only after 1945.

He had a love-hate, or even an abusive relationship with his home country. In an interview, he said,

It’s the country of my origins – that, I think, is what matters in the end, whether one likes it or not. Certainly, I had to experience the outside world and would have felt deprived if I didn’t have that behind me. But it’s from the Australian earth, Australian air, that I derive my literary, my spiritual, sustenance. Even at its most hateful, Australia is necessary to me.

Yet the Nobel Prize came to Australia at a time of surging cultural nationalism. In 1972 the last social democratic government to be elected in Australia came to power determined to crash through the old ways. It implemented policies to break the last shackles of British imperialism in Australian culture, and protested the new chains being secured by American dominance. It sponsored many policies that promoted the arts. White’s Nobel Prize vindicated this new cultural nationalism.

But White was uneasy with any nationalist movement, especially in the arts. He was an exile at home. His life and work were representative of the uneasy post-1945 Australian cultural elite, coming to terms with their own cultural decolonisation and nationalist breakout. His novels are superb examples of 20th century modernist European literature, set in a new continent, but deriving from the literary traditions of the old continent. His novels explored the stranger, the outsider, and the outcast. His characters search inwardly for imaginative salvation in a hostile culture. White once said, “I am the stranger of all time.” It sums up his work.

His major works include:

The Tree of Man (1955), a retelling of the classic Australian (or European settler colonial) pioneering saga

Voss (1957), which is based on the story of German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt and a fictional relationship with a colonial spinster, Laura Trevelyan

Riders in the Chariot (1961), which depicts four 'riders' who are outcasts from mainstream Australia, which is intolerant of difference and prone to cruelty

The Solid Mandala (1966), the story of twin brothers, one a sterile intellectual, the other an instinctive lover of life

The Eye of the Storm (1973) is a portrait of the dying but indomitable Elizabeth Hunter, based in many ways on White’s own wealthy family

Fringe of Leaves (1977) A historical novel loosely based on the story of Eliza Fraser, who was shipwrecked on Fraser Island and lived among the Aboriginal community there

The Vivisector (1970), which is set in Sydney during the first half of the twentieth century, and portrays a male artist (Hurtle Duffield) as its central figure with all the cruelty “great artists” are capable of.

The Twyborn Affair (1979), which switches between male and female roles in a way White himself was only able to do in his imagination.

I have produced three pieces on White over the last two years, and rather than repeat them I will point readers to them:

Patrick White, Nobel Prize and Australia’s aborted cultural decolonisation

Burning Archive Podcast episode 119. Why read Patrick White, 1973 Nobel Prize for Literature, the Exile at Home?

Do read White; not because he is Australian, but because you will encounter late modernist writing in the most intense poetic and mythic language. Through his works you can explore how the myth of the stranger is an idea with power and poison; how this idea often alienated 20th century artists from the society that was their haven.

1974 Eyvind Johnson (1900–1976) Sweden

1974 was a strange year in the history of the Nobel Prize. It is the last year, to date, in which two prizes were awarded. The two prizes went to Swedes. Both were writers labelled as “proletarian writers”. One wrote prose. The other wrote poetry. But both were members of the Swedish Academy. The Swedish press then accused the Academy of favouring its own. It created quite a scandal. The American press yawned. Their President Nixon had resigned under threat of impeachment two months before. They had bigger scandals to fry.

Let us start with the prose writer, Eyvind Johnson. He was a notable, ground-breaking Swedish novelist. His language, however, did not translate well to English. Only four books were translated. Johnson is now barely known in the Anglophone world.

He was a working-class autodidact, who made a successful life as a writer despite adversity. He dabbled in left-wing politics. His background influenced his early vague support for socialist causes. In the 1920s he dallied with the peaceful anarchism of Kropotkin. He opposed authoritarian movements in the 1930s, and, like Orwell, embraced the cause of the international brigades who fought for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War. But on the eve of World War Two his wife died suddenly. Stories, not politics, would now sustain him during the war and beyond.

His fiction was modernist but suspicious of grand narratives. He wrote a series of novels about the Swedish experience of the war that remain important in Swedish public memory. He wrote several autobiographical novels that mingled irony, realism, and fantasy. He wrote several major historical novels that achieved renown outside Sweden. These works included Return to Ithaca: The Odyssey Retold as a Modern Novel, which experimented with narrative voice. It might be compared to the even bolder Ulysses of Joyce… if I could find a copy.

His most praised work is the The Days of His Grace. This novel is set in the time of Charlemagne (748-814 CE), the Frankish Holy Roman Emperor. In 775 Charlemagne conquered Northern Italy. The novel follows the story of one family whose lives were changed by this invasion and the domination of the old ruler of Western Europe, Charlemagne. It relates their ways of coping with subjection to the arbitrary and overbearing power of absolute monarchy and how they suffer when they rebel against Emperor Charlemagne. It sounds like a historical novel of a Swede processing the European traumas of Napoleon, Hitler, and Stalin.

I have not been able to source the novel itself, but from the Gale Dictionary of Literary Biography I can share this brief reflection by Johnson on his philosophy and psychology of writing.

I have said it before and will say so thousands of times: I live to write, I was born to write, it is my instinct. I would write books on birch-bark and with the sap of longan-berries, were there no other means. I would write in the dark, were there no light. I am neither proletarian, nor aristocrat: I am one who writes, who is intended by instinct, by fate, to write.

You can read more about him in Swedish here, and read a brief translation of an excerpt from The Days of His Grace here.

1974 Harry Martinson (1904–1978) Sweden

Harry Martinson was the proletarian Swedish poet who shared the honours with Johnson in 1974.

He was better known internationally than his prose writer friend. He was an innovative modernist poet. But his poetry was lyrical, not obscure. He was a popular, important figure in Swedish literature.

Like Johnson, he came from the rough end of town. His father was a brawler and a drinker, who had worked for a time in Australia. Martinson made his way from his late teens as a seaman and worked many proletarian jobs. But he was driven to write.

He found his way to mentors, including the older woman writer, the novelist Moa Martinson, who would later become his partner. She partnered Harry after her husband suicided by blowing himself up with a stick of dynamite, the explosive that made Alfred Nobel the fortune he bequeathed to his Prize.

Harry and Moa Martinson embraced a writing partnership and shared political journey. Together they visited the Soviet Union in the mid 1930s. But Harry did not share his partner’s enthusiasm for communism nor the discipline of the political party. He was more inspired by the rebel Russian poets, Yesenin and Mayakovsky.

Politics alienated Harry from Moa. The poet evolved in a direction distant from the Left and critical of modern technological, industrial modernism. He wrote nature books and celebrated the environment that the industrial explosions of the left and the right, of capitalism and communism, were destroying. In the later decades of his life, he stopped writing.

His works are hard to find now in English, but I have found this fragment that I can share in Swedish and English.

Bäst är människan när hon önskar det goda hon inte förmår

Och slutar odla det onda som hon lättare förmar

Då har hon dock en rikting. Den har inget mål.

Den är fri från hänsynslös strävan

Best is man when he wishes for the good he cannot achieve

And ceases cultivating the evil that he more easily achieves.

Then at least he has a direction. Which has no goal.

It is free from ruthless striving.

By the time he had won the Prize, Martinson had long turned his back on literature and politics. The scandal of the two insider Swedish prizes of 1974 brought him back to centre stage. It unleashed many criticisms of Martinson in Swedish intellectual circles, not least for his lack of political engagement. But Martinson was a sensitive soul and could not cope with the criticism. In February 1978, he committed suicide by cutting his stomach open with a pair of scissors in what has been described as a "hara-kiri-like manner".

The 1970s were bad years for writers and suicides. Thank God, mental health care is a little better today; even though the envy and spite of intellectuals, who compete for the same petty prizes, never diminishes.

You can directly support my work by becoming a paid subscriber or supporting me through the Tip Jar at Buy Me A Coffee.

Links to bonus archival video footage

1968 Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972) Japan

1969 Samuel Beckett in Sweden in Berlin (1906–1989) Ireland/France

1970 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) Soviet Union/Russia

1971 Pablo Neruda (1904–1973) Chile

1972 Heinrich Böll (1917–1985) Germany

1973 Patrick White (1912–1990) Australia

1974 Eyvind Johnson (1900–1976) Sweden (1 of 2) - could not find any

1974 Harry Martinson (1904–1978) Sweden (2 of 2) - could not find any

Kawabata's Master of Go is a gorgeous and enigmatic story of a luminous talent overtaken by the passing of time. I've read it several times and recently during the pandemic. It's beauty is what's left unsaid.

I just wanted to pop in and say I've had a great day rereading and listening making notes on the Globalisation post, and on this post. Then I read more "Civilization". I'm about to listen to the Proms, Benjamin Brittain's "War Requiem". So most of today's pleasure ha been Burning Archive related, the rest the LSO. Thanks, I finally got my head around the difference between the media's idea of globalisation and that of internationally focused historians. Now I need to source the books on the subject.