Glimpses of the Multipolar World, 29 April 2023

MacGregor, Europe, China, Bureaucracy, Madness, Pessoa, Phillipines

Each week in my newsletter, I offer seven glimpses for seven days of the multipolar world. This week, I share glimpses of:

Gratitude. Douglas MacGregor

Reading. Europe-China rapprochement and Western unravelling

Governing the Multipolar World. Bureaucracy in fragmented states.

Using History Mindfully. Changing ideas of madness.

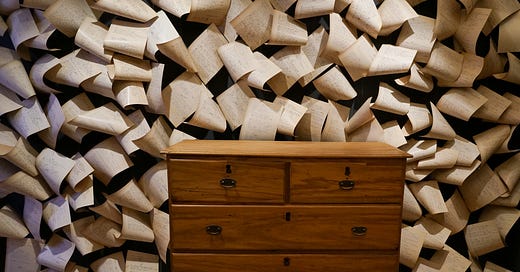

Fragments of the Burning Archive. Pessoa.

What surprised me most. America’s bloody hands in the Phillipines

Works-in-Progress. 13 Ways of Looking at a Bureaucrat.

The Burning Archive is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1. Gratitude

I am thankful for Colonel Douglas MacGregor for his integrity, courage and candour. He has told the truth about the war in Ukraine and the illusions of the American and Atlanticist elites. Gradually, people are realising how those elites have brought tragedy and ruin to Ukraine, Europe, America and the world. Thank you, Colonel Douglas MacGregor.

2. What I am reading

In addition to continuing from last week my reading of Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers, I read two fine articles that gave glimpses of the multipolar world.

The first article by M. K. Bhadrakumar (‘Who gains from a forever war in Ukraine?, Indian Punchline) commented on Europe’s positioning in the emerging multipolar world. The article raised a question I discussed in The Burning Archive Podcast 97. Macron, European Sovereignty, and Reflections on a Philosopher President. Is Macron serious about pursuing European independence in a multipolar world? Bhadrakumar made the telling point that three countries - France, Germany and Italy - account for more than half of European GDP, and these three countries are China’s largest European trading partners. The leaders of all three countries have signalled that, while they will go along with American grand illusions in Ukraine, they will not join the next American crusade against China in Taiwan. Such an act would only devastate their own economies and societies. He concluded his article with the prediction,

as the Ukrainian military is comprehensively ground down in the battlefields by the Russian forces in the months ahead, Europe may join hands with China to bring the war to an end.

His comment seems prescient following the call between Xi JinPing and Zelensky on 26 April 2023. Xi told the Ukrainian President he needed to look to the long-term future, and “jointly explore ways to bring lasting peace and security to Europe through dialogue.”

I also read Paul Kingsnorth, “The West has Lost its Roots” Unherd September 2021. It commented on the cultural hole in the Western heart. “We in the West are living inside an obsolete story. Our culture is not dying - it is already dead.” Kingsnorth might say this hole is in the spirit. Provocative, and worth reading.

3. Governing the unruly multipolar world

I have been editing for publication 13 Ways of Looking at a Bureaucrat, in which I have included transcripts of my podcasts on bureaucracy and political decay:

By chance, I released these podcasts in June 2021, the same month that Kingsnorth published his article. Editing them reminded me how simplistic is most public commentary on bureaucracy, including in relation to international affairs. It emotes about the spectacle of the political leaders, and does not observe the fragmented reality of the whole state executive.

Bureaucracy is essential to good government, political executives, and state capability. In these podcasts I developed ideas from Fukuyama, Political Order and Political Decay about the foundations of political order. He argued political order rests on a triangle of accountability, rule of law, and state capability, but successful polities require the skilful balance of culture and institutions against basic drives of human sociability. In that sense, bureaucracies, and successful political orders, are miracles of social organisation, ingenious arks of culture.

Regrettably, they are more easily destroyed, than built or maintained. Faulty bureaucracy and fragmented political executives are much in the news today, and behind the dynamics of the world crisis. Are they not part of the problem of Western leadership? Have they not made the fiasco of Western dipomacy in recent decades?

Failing bureaucracy and decadent political cultures are not only international stories. They affect domestic governments. They affect the minor provincial government in which I worked for 33 years, Victoria. While I write stories of the multipolar world on this newsletter, I will not let slip in my writing the tragedy of what has happened in Victoria. It illustrates I think many problems of life after Western, liberal democracy. It is an index case of failing, fragmented republics in distress.

So I will return to it, over coming months, especially after learning this week that the Victorian Ombudsman inquiry into politicisation of the public service has not gone gently into that good night. It has not succumbed to the churning oceans, unlike most so-called journalists and political commentators.

4. Using history to live mindfully in the present.

To live mindfully is a way to stay sane. To stay sane in the current world crisis is a daily task, and no small achievement. It is not surprising that the meme of the ‘World has gone crazy’ is so common. But to live mindfully amidst this crisis, we must not drive ourselves mad with misleading narratives about the history of madness, mental illness or insanity. Too often, unreliable prophets proclaim the collapse of civilization, another fall of Rome, when they notice people behaving irrationally, or in ways that offend their moral code or with minds that seem a little bit deranged. These histories of derangement, however, define the harmonies of our histories of good order, whether in government, culture, society or our own confined lives.

During the years of the pandemic, I read again Michel Foucault’s History of Madness. When I was a university student, I had read Foucault obsessively, and even conceived my own PhD in his tradition, as a kind of history of the truth of class. Indeed, I read everything that Foucault ever wrote, even texts in French that had not yet been translated, like his La Histoire de la Folie (1961). But then I put him aside, and shed many of his ideas. I discarded the theories and the radical, melodramatic politics, but I always retained an affection for the text in which I encountered Foucault’s most rhapsodic historical metaphors, like the chapters from History of Madness (or the abridged edition, Madness and Civilization) on the Ship of Fools, the mad artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, and the Great Confinement.

When the pandemic hit, when we were all locked down, when new systems of ‘biopolitics’ came into force, I turned back to Foucault as a seeming prophet of our times. If the mad were shuttered into the old leper houses in France’s 17th century Great Confinement, it seemed to me in 2020 that the sane and insane were all shut down in the Great Seclusion of the 21st century. However, Foucault’s narratives did not hit me with the force they had on my 19 year-old mind. By 2020 I had accumulated three more decades of experience with mental illness, its relationships to our political, social, cultural and personal orders, and the real dilemmas of governing madness. I could separate the poetry from the postures.

But the deep truth of Foucault’s poetic history - that madness has a social and cultural history beyond the body, brain, chemsitry and genes - still echoed through the events of the pandemic, and more broadly the large social, cultural and political changes to the orders of mental illness over the 60 years since his La Histoire de la Folie (1961). Psychotropic medicine. Deinstitionalisation. Lived Experience. Patient Rights and Advocacy. Identity Politics. Decentering of the West. Compassionate psychology. Mindfulness. Many failed attempts to ‘reform’ mental health. The way our cultures imagine or tell the story of their relationships to madness is changing again. This is the issue I talk about on my podcast this week. And in weeks to come I will turn to reflections on why governments keep failing on mental health.

On the podcast I also included brief clips (full details linked) from a rare early 1965 interview with Michel Foucault and the extraordinary voice of the experience of madness, Antonin Artaud, in his 1948 radio broadcast, To Have Done With The Judgement of God. Both videos are in French, and can be auto-translated on YouTube.

5. Fragments from the Burning Archive

I began reading a recent acclaimed biography of Fernando Pessoa, Richard Zenith, Pessoa: An Experimental Life (2021). Pessoa is a writer from the Burning Archive pantheon. His fame is largely posthumous. He wrote largely in fragments. His texts are miracles of survival, and later uncertain reconstruction. He wrote in an elaborate form of pseudonyms, which he called heteronyms. These heteronyms were more than concealing masks. They were whole, imagined personas in which Pessoa (which means person in Portugese) wrote in distinct style and with invented back stories. He published major poems in the name of three of these heteronyms, as well as his own name. It is said then that the four greatest Portugese poets of the twentieth century are all Fernando Pessoa.

He wrote large numbers of unpublished, fragmentary texts that he stored in a trunk in his home in Lisbon. The trunk was discovered well after his death. This home has been converted to a literary museum, Casa de Pessoa, where the trunk, texts and heterotopy of international poetry are commemorated today. In the trunk, there was one envelope of disordered texts, which has been published in various scholary reorderings as The Book of Disquiet. It joins the other enigmatic texts, such as Beowulf or the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, celebrated on The Burning Archive for their miraculous outwitting of the fires of oblivion.

Pessoa left a legacy of a multi-persona person. He personified fragments of the cultural heritage of the multipolar world. His biography spanned Portugal, Britain and South Africa. Let me share two fragmentary statements from this fragment of the Burning Archive that stand as guiding flags for my writing.

The only way to be in agreement with life is to disagree with ourselves.

(Bernardo Soares, one of the major heteronyms of Pessoa)

Be plural like the universe!

6. What surprised me most this week.

I was surprised when reading Christopher Clark, Sleepwalkers about the extent of threat to peace posed by Britain and America in the decades leading up to World War One, rather like today. Here are two examples of the surprise.

On Britain. In 1900, French Foreign Minister Théophile Delcassé (1852-1923) said “Britain was a threat to world peace,” and that the time had come to take a stand “for the good of civilization.”

On America. Clark countered the common Anglo-American focus on the aggression of Germany as a challenger to the hegemon. He noted that any German aggression or adventurism was exceeded by America. In the few decades before 1914, America took over Cuba and invaded or claimed islands in the Pacific, including Hawaii, Wake, Midway, Guam, and the Phillipines. After taking over the Phillipines as a colony from Spain, America conducted a war against the insurgents in which up to 750,000 Philipinos were killed by the empire that today dare not say its name. I did not know the expansion of the peaceful American empire had undone so many. So began the bloody American century.

7. Works-in-progress and published content

This week my works-in-progress and published content were:

on the podcast I published Episode 98. Madness and Western Civilization, Today

On the YouTube Channel I published videos:

I drafted short essays and edited the podcast transcripts in 13 Ways of Looking at a Bureaucrat.

On Twitter, I had a quiest week but David Kersten was kind enough to tweet this about my op-ed/essay, The Derangement of the American Mind https://twitter.com/davidkersten/status/1650285852805971968

Let me know if there are issues or topics you would like me to talk about on the podcast or the YouTube channel or on the Sub-Stack.

Next week…

The podcast will be on the derangement of the democratic mind during the pandemic, and whether we all experienced collective forms of mental disorder.

On Youtube, I have not decided yet. It will come out Tuesday night though.

Please consider supporting my writing and help me reach an audience who may benefit from any insights I can share.

First of all, please subscribe to this newsletter on SubStack. You can subscribe for free and as a paid subscriber to receive bonus content. Please share with your network.

The Burning Archive is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Please also subscribe to my YouTube Channel.

Follow me on Twitter.

And you can buy my books.

my book of essays From the Burning Archive: Essays and Fragments 2015-2021.

my collected poems, Gathering Flowers of the Mind.

Please share this newsletter with a friend.

I will be back in your and your friend’s inbox next week.

And do remember, “What thou lovest well will not be reft from thee” (Ezra Pound, Cantos)

#4 is important Yet the most forgettable for American society. Media and politicians have determined most mindsets and created conflict. The building blocks of character and integrity have been flushed down the loo; identity has become politicized(left vs right, race, religion)and sexuality is now identifiable as a political ideology/strategy. Mental illness is a badge of honor in our culture, it’s used to prescribe medication and test treatments that are life threatening/altering. Our country is sick in many ways. Those whom are under the sickness need real help, not more big pharmaceutical lies or propaganda. Thank you for consideration of all aspects and not falling into the cycle of violence and decay we are experiencing. We need change and in order to bring so about, we need our hearts to stay grounded to our soul and minds to gain clarity for our judgments to be consistent.