Olga Tokarczuk's tender narrator of Nobel histories

The 2018 Nobel Prize for Literature went to Olga Tokarczuk whose writing crosses borders, plays with genres, and tenderly shows us how to live well now by reading history and literature.

Tokarczuk is the perfect writer to end the 120 Nobels Reading Challenge. I discovered her through the Nobel Prize. I enjoyed her masterpiece of historical fiction, The Books of Jacob, more than any other novel I have read in the last twenty or thirty years. Tokarczuk is a historical writer of the highest order. She belongs in both the Nobel Hall of Fame and the Burning Archive.

The seven winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature between 2017 and 2023 were:

2017 Kazuo Ishiguro (b. 1954) Japan/Britain

2018 Olga Tokarczuk (b. 1962) Poland

2019 Peter Handke (b. 1942) Austria

2020 Louise Glück (1943–2023) USA

2021 Abdulrazak Gurnah (b. 1948) Zanzibar/Tanzania/Britain

2022 Annie Ernaux (b. 1948) France

2023 Jon Fosse (b. 1940) Norway

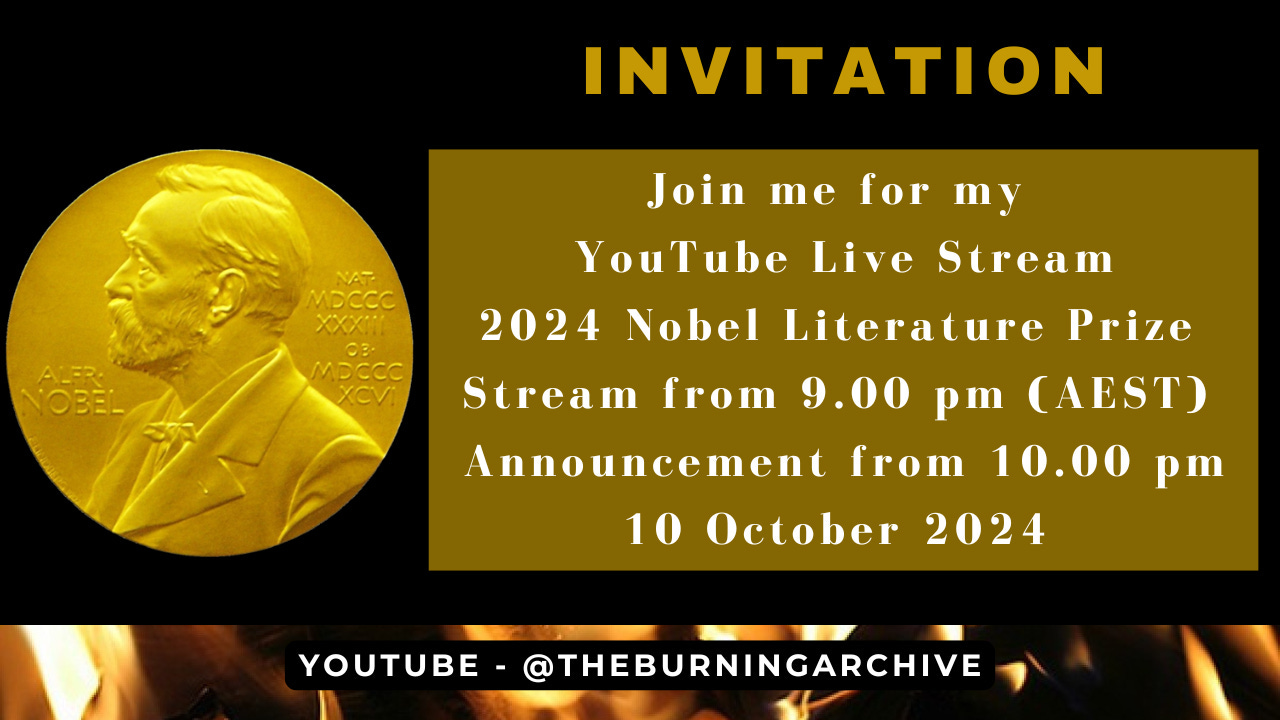

You can watch my profile of these seven winners on the Burning Archive Youtube Channel on Sunday night, including my reading of Louise Glück’s poem, “Wild Iris”. From November, I will reassemble these notes in the Nobel Archive, the new home of the 120 Nobel Prize Reading Challenge.

Olga Tokarczuk, The Tender Narrator

Olga Tokarczuk described our contemporary social media experience of a confusion of narratives in her Nobel lecture, entitled, “The Tender Narrator.” She said (in Polish, since translated into English)

We live in a world of too many contradictory, mutually exclusive facts, all battling one another tooth and nail.

In Tokarczuk’s vision, narratives can confuse us, but they can also guide us to a deeper compassion for the world. The spinners of narratives can be simplistic, brutal, crass and manipulative. But there are also tender narrators. Tokarczuk is one of them. She said at the conclusion of her Nobel Lecture:

“Greed, failure to respect nature, selfishness, lack of imagination, endless rivalry and lack of responsibility have reduced the world to the status of an object that can be cut into pieces, used up and destroyed.

That is why I believe I must tell stories as if the world were a living, single entity, constantly forming before our eyes, and as if we were a small and at the same time powerful part of it.”

This beautiful lecture was delivered late, in 2019. History will record Tokarczuk as the Nobel Laureate of 2018, but her prize was delayed to 2019 by a sex scandal involving the Swedish Academy.

In 2017 a major Swedish newspaper published testimonies of 18 women who said that they had been assaulted or exploited by Jean-Claude Arnault. Arnault was married to the poet and member of the Swedish Academy, Katarina Frostenson. The allegations would be sustained; Arnault would later go to jail.

The scandal exposed a rotten culture within “The Eighteen”, the Academy members who choose the winner of the Nobel Prize. There was financial corruption. Leading members of the Committee displayed “rotten macho values and arrogant high-handedness.” There was an opaque culture of secrecy that concealed poor decisions and widespread abuse and under-representation of women.

In response to the exposure of this rotten culture, one third of the Academy resigned or were expelled. As a result, in 2018 the Academy could not form a quorum to decide on the Prize. The prize was deferred and to the credit of the Nobel Prize they improved their procedures. It redeemed itself, and set a new course for a more open communication about the Nobel Prize and more accountable procedures.

Olga Tokarczuk had to wait a year to receive the Prize in late 2019. But Tokarczuk, a strong feminist voice and a tender narrator, was a wise choice for the Nobel Prize’s new kinder, more open and more feminine phase.

Olga Tokarczuk biography

The Nobel Prize helped to widen Tokarczuk’s readership outside Poland. Within Poland, however, she had been a popular, celebrated writer for decades. Her tender stories offered healing for a nation that had suffered, and inflicted, many traumas over the last three centuries. Tokarczuk’s biography created a path for her writing to be a compassionate response to Poland’s plural histories.

Olga Tokarczuk was born into a family of teachers in Sulechów near Zielona Góra (Green Town) in 1962. She trained as a psychologist at the University of Warsaw in the early 1980s while the Warsaw streets were full of the turmoil of Solidarity, protests, martial law and resistance to Communist or Soviet rule.

Her experience of growing up within the controlled Soviet and then post-Communist society influenced the themes of her fiction. She writes of travel, diversity, openness to change and innovation. She celebrates heresy. In her teens she perceived the world as closed off to her. She sought to go on fantastic journeys through history, with the help of her imagination, to escape the iron trap of Poland. In an interview, she said

“Everything that was interesting was outside of Poland. Great music, art, film hippies, Mick Jagger. It was impossible even to dream of escape. I was convinced as a teenager - that would have been like the mid-70s as a teenager - that I would have to spend the rest of my life in this trap.

After university, she worked as a clinical psychologist for a decade or more treating alcoholics, and started a family. Her approach to psychology was influenced by Carl Jung and the emphasis on the archetypal unconscious, the mythological imagination. This influence also came through in her writing. It was the base for the deep, brilliant characters in her fiction.

Until 1990 Tokarczuk published small prose fragments and some poetry. It was not until 1993 that her debut novel was published. It received awards and helped to establish some financial security for Tokarzuk and her family. They relocated to a small estate village near Nowa Ruda in the Sudeten mountains in 1994, where they still live.

There her writing and approaches to life and politics bloomed. She wrote a series of novels and essays that established her as a leading writer in Poland. Many dealt with Polish history, literature and culture. But all transcended national culture to speak to wider issues, such as those addressed in her Nobel Lecture, “The Tender Narrator”.

Her political commitments are to dialogue across national limitations, to animal rights, to feminism, and to environmentalism. She is reported to be a member of the Green Party, and all these themes come through in her writing. Poland is a country that has been devastated to some degree ecologically by dirty industrialisation, during both the Soviet and post-Communist period. Today it is integrated into German industrial economic networks. It and neighbouring Ukraine are also major agricultural countries. Tokarczuk’s animal rights beliefs are controversial in the country, but integral to her fiction. She said in an interview

I'm not that type of activist. I'm too neurotic and too nervous to make a speech to a big group of people. I'm not this kind of fighter, but what I can do is I can invent some ideas and I can write down those ideas and I can create a story which will move other people like Drive your plough over the bones of the dead. And after this book, many people told me that they became vegetarian.

Despite their success, Tokarczuk’s novels have many enemies within Poland. They challenge a traditional narrative of Polish history as the monocultural Catholic nation victimised by outsiders. Tokarczuk presents a different story, especially in The Books of Jacob, of how Poles contributed to the demise of a Republic of Many Nations, and the catastrophic liquidation of its multicultural character in the Holocaust. Rather than conservative or neoliberal Polish nationalism, Tokarczuk cherishes an old idea of a multiethnic, multicultural, multifaith Europe.

Her pluralism has made her a controversial figure in Poland. But the fame and prize money of the Nobel Prize have enabled Tokarczuk to spread her vision and compassion through the Olga Tokarczuk Foundation. This foundation explains its aims as:

We are an independent non-governmental organization, aiming to support and promote Polish and world culture and art in Poland and abroad, as well as to promote and support the broadly understood protection of human rights, democracy, civil society, civil liberties, to counteract discrimination, support women’s rights, and promote and support wide-ranging development of Poland, and in particular of Wrocław, Lower Silesia, Lubusz Land, as well as Wałbrzych and Kłodzko districts.

Tokarczuk has led the annual literary festival, The Mountains of Literature Festival, to become Poland’s major writers festival. Tokarczuk and the festival promote a culture of plurality and dialogue in the belief that “such conversations change the world”.

But prior to the 2024 Festival, Tokarczuk received death threats and was the target of hate speech. Nevertheless, the Prize and her books have made Tokarczuk into a major writer of transnational European culture. The Books of Jacob was a national bestseller in Poland for months in 2014. The Nobel Prize has deepened her connections across the world and contribution to Polish culture, and not turned her into a hack on the American speaking circuit.

The Books of Olga Tokarczuk

Olga Tokarczuk won the Nobel Prize at a relatively young age of 56, while still in her prime writing years. Since the Nobel Prize she has published two novels in English translation. She has not rested on her Nobel laurels, nor suffered the Nobel curse.

Only this month, The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story came out, after being published in Polish in 2022. It is historical fiction, philosophical novel, horror story, and a modern feminist response to Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. Her feminist perspective comes through strongly in The Empusium where men bluster ideas about power and women, while underground female spirits haunt them. It is set in a mountain sanatorium in 1913 on the brink of world war. Does it sound familiar?

In late 2021 the English translation of The Books of Jacob (2014) was published. It is a historical fiction and an epic thousand page novel with real insights into writing history. It is funny, inventive and profound. It takes you all the way from seventeenth-century Poland through to the Holocaust by tracing the story of Jewish cult leader, Jacob Frank and the remarkable narrator Yente. It was in many ways the masterpiece that won her the Nobel Prize.

Her work is varied and plays with genre and gender. Her versatile range and stylistic capability is another great reason to read Olga Tokarczuk.

Drive your plough over the bones of the dead is a kind of crime mystery novel related to an eccentric animal activist character. In a remote Polish village, Janina spends the winter studying astrology, translating the poetry of William Blake, and taking care of the summer homes of wealthy Warsaw residents. She appears to be a crank and a recluse who cares more for animals than humans. But she becomes central to solving a murder mystery haunting the town.

Flights is the story of travellers, wandering, migration and the search for unstable identity. It celebrates crossing borders. It combines essays, fiction, monologue and fragmentary social observation. It reminded me in ways of W.G. Sebald’s collage of travelogue, fiction, history, and puzzled reflection on the destructiveness of humanity. Like The Books of Jacob, this novel is a celebration of crossing borders and the pilgrimage we all follow in the search for meaning. In her 2000 essay, The Doll and the Pearl, she wrote

A pilgrimage is setting out on a journey, a symbolic act, a great decision. It involves a change of the viewpoint, adopting a new perspective, a try to make yourself anew, readiness to renew oneself.

Reading Tokarczuk for compassion

I love Tokarczuk’s writing because of her compassionate, pluralist, tender way of thinking about history and literature. Indeed, critics have described her as one of the major thinkers of the twenty-first century who write about history. The critic, Andrzej Mencwel commented that

Olga Tokarczuk is a historical writer of the greatest sort - not only does she know what needs to be known about the world portrayed by herself but also she is able to present it in detail, and guides the attentive reader into thinking about her stories. And the stories are complex since they are polyphonic and multicultural.

I aspire on the Burning Archive to do something similar; so Tokarczuk offers a wonderful model for my own fantastic journeys through history. She is a model for me in her style, her ideas and in her compassion. In this crazy-making world, which appears to be unravelling, we need to read history and literature with compassion. Compassion drives Tokarczuk’s writing. As she said in an interview,

I believe that pain rules the entire world. That is something which is obvious for me. And to understand what's going on around us, the first subject should be to concentrate on pain and on suffering. Especially, it's important for writing because you cannot really figure out what's going on with other people if you don't understand the pain and the suffering. So I think sometimes that this is the most obvious, most common level we communicate. This is compassion.

Would you like to do a slow read of Tokarczuk?

I am considering offering next year on The Burning Archive a slow-read guide to Tokarczuk, The Books of Jacob and possibly her new novel, The Empusium. I sketched this idea in this post—“Fantastic Journeys through History.” Several Substack publications offer these slow-reads, such as Simon Haisell, who reads a chapter a day of War and Peace through the whole year.

So I can gauge your level of interest in doing a slow read could all readers please respond to this poll about whether you would like to participate in an online book club, slow-read of Olga Tokarczuk, The Books of Jacob and The Empusium.

I am planning out my content for the next six to twelve months over October so I would love to hear from you about how I can best make the Burning Archive a resource for readers to learn from history and literature to live well now.

I will be reading Tokarcuk’s Nobel lecture “The Tender Narrator” in my mini-audiobook series (for paid subscribers) in the post scheduled for 14 October.

If you believe the world needs more compassionate, pluralist stories told by tender narrators, you can help make that happen by becoming a paid subscriber to the Burning Archive.

Absolutely love Tokarczuk's writing and ideas and will definitely take out a paid subscription if you go ahead with this.

"Tell me more": I was planning to schlep The Books of Jacob with me to my hideaway in Portugal for the next seven weeks, but it is quite possible that Jennifer Croft's brilliant translation would merely stare at me reproachfully the entire time and I would schlep it back home, weighted down with more unmet expectations. How does this "slow read" work? How slow may I be?