Forgotten, Famous and Favourite Nobel Literature Prize Winners (1907 to 1913)

120 Nobels Challenge * WEEK 2 * (1907-1913): Kipling to Tagore

Since 1901 the Nobel Prize for Literature has been awarded to 120 writers. Many of the earliest have been forgotten. A few are still read today. Over 120 days, from June to October 2024, I will read every single winner of the Nobel Prize and offer you some glimpses of their work and their part in the history of the multipolar world.

Please join me on this ultimate literary pilgrimage and booklover’s challenge. At the end you will be able to tell your friends that you are one of the few readers on this planet to have read at least a little of every single winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

This week I introduce you to the winners from 1907 to 1913, who began with the great, well-known writer of British Empire in India and ended with the greatest writer of this set whose songs and essays helped to defeat the British Empire and Western nationalism.

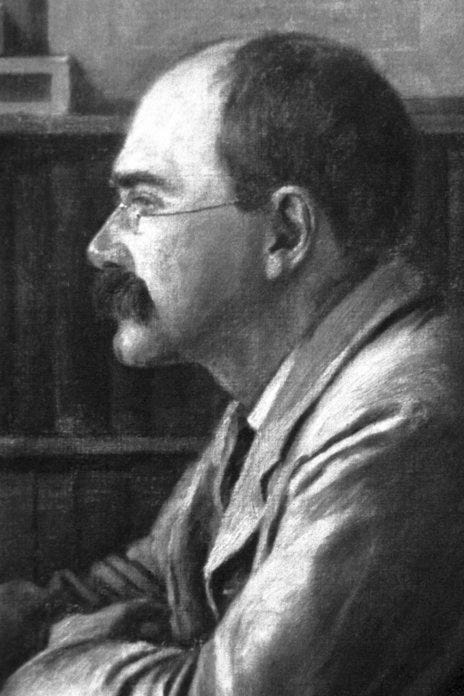

1907 Kipling (1865-1936, Britain or British India)

You might claim that Rudyard Kipling was the first Indian Nobel Prize winner since he was born in Mumbai, then Bombay, and made his early career as a writer in the Anglo-Indian community of the Raj. Yet Kipling is remembered as a poet of empire, even if some of the ambiguities of his affections have been blurred in time.

His fiction is well known (the Jungle Books (1894-5), Kim (1901), and short stories, such as "The Man Who Would Be King" (1888). These stories have been made into successful films, making Kipling the best known of the early Nobel winners.

His poetry included the era-defining "The White Man's Burden" (1899), and the more personal "If—" (1910) that in its advice from a father to a son transcends time. This hymn to heroic masculinity has enjoyed a new popularity on YouTube through a superb reading at RedFrost Motivation. It was even made into a Trump commercial in the 2020 election campaign.

Kipling was and remains the youngest winner of the prize at 41. In honouring him, the Nobel Committee honoured the world’s largest empire of the time. It is symbolic that the first English language writer to win the Nobel Prize is inextricably bound to its empire. Empire was the subject of the poem that became a symbol of 20th century empire and colonialism, “White man’s burden.”

Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go, bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait, in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

This poem has been interpreted in different ways, as a call to assume the responsibilities of empire, and a warning of the moral hazards of doing so. In 1899, the poem was read in a debate in the USA Senate over whether the republic of freedom should subject the Philippines to its new style of Empire. The historian Niall Ferguson used the poem to urge Americans to take up the responsibility of empire through the USA’s endless wars in West Asia.

It is telling that the Nobel Committee in these early years celebrated British imperialism alongside insurgent nationalism in some European empires. But as we will see, by 1913, on the cusp of the Great War that ended some of these empires, the Nobel Committee was having second thoughts.

1908 Rudolph Eucken (1846-1926, Germany)

In 1908 the Nobel Committee showed its broad-minded concept of literature by choosing a philosopher. They also chose a writer affiliated with German culture, which at this time was the pride of Europe.

Eucken practised an engaged spiritualism, which in turn was a kind of aversion to the emerging modern world. In the era of 1880 to 1914, spiritualism was common among the cultural elites of Europe, Russia, and non-Western states. Madame Blavatsky was an international celebrity. The Australian Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, spoke with the dead at séances.

Eucken described his philosophy as "ethical activism." He avoided arid intellectuality, and sought to connect religion, spirituality, and the problems for the European elites of reconciling these visions with the immense social problems of a newly industrialised, urbanised societies.

He was prolific writer, and his best-known works are The Problem of Human Life as Viewed by the Great Thinkers) (1890), Life's Basis and Life's Ideal: The Fundamentals of a New Philosophy of Life (1907), Can We Still Be Christians?, (1911), and Socialism: an Analysis (1920).

This brief excerpt from (Life's Basis and Life's Ideal: The Fundamentals of a New Philosophy of Life) 1907 will give you a taste of his writing.

“But where the life of the individual acquires a genuine being and a connection with the realm of self-consciousness, then, notwithstanding all that is fleeting and insubstantial, the individual cannot regard himself as a transitory appearance in the whole, even in the ultimate basis of his being. … As the world, as a whole, is in the highest degree mysterious to us, so our future is veiled in the deepest obscurity. But, if with the essence of our being we are elevated into a universal spiritual life, and if in the innermost basis of our life we participate in an eternal order, then the time-transcendence of this life assures to us also some kind of time-transcendence in our being.”

Even dull writers have won the Prize. Again, the Nobel Committe looked back to the late 19th century traditions of European culture, its religiosity, spiritualism, and desire for social reform. I doubt Eucken is read much these days; he is a philosophical relic. The following year the Nobel Committee chose a greener shoot of history.

1909 Selma Lagerlöf (1858-1940, Sweden)

In 1909 the Nobel Committee chose the first pure Swede and the first woman to win the Nobel Prize. Selma Lagerlöf was a novelist, social reformer, and leading advocate of women’s suffrage.

Sweden would not give women the vote until 1919, and later still would honour Lagerlöf as the first woman on a Swedish bank note, eighty-two years after her prize in 1991. The Soviet Union had honoured Lagerlöf decades earlier as a hero of the Soviet Union on a postage stamp. The influence of the legendary socialist feminist and USSR Ambassador to Sweden, Alexandra Kollantai, may have played a role in this celebration of an early feminist.

Among the famous quotes of Lagerlöf is an accurate observation of civilian and female suffering in war: “More die in flight than in battle.”

Her major fiction includes Gösta Berling's Saga from which this brief passage comes:

“... I see the green earth covered with the works of man or with the ruins of men’s work. The pyramids weigh down the earth, the tower of Babel has pierced the sky, the lovely temples and the gray castles have fallen into ruins. But of all those things which hands have built, what hasn’t fallen nor ever will fall? Dear friends, throw away the trowel and mortarboard! Throw your masons’ aprons over your heads and lie down to build dreams! What are temples of stone and clay to the soul? Learn to build eternal mansions of dreams and visions!”

You can listen to this novel at Libri Vox, and read an online edition of the book.

Lagerlöf is the first winner of the Prize to represent a movement that transformed twentieth century societies worldwide, feminism. Yet she also sprang from movements that had transformed the global nineteenth century. Her father was likely an alcoholic, and the temperance and women’s suffrage movements were intertwined in the nineteenth century.

Lagerlöf’s transatlantic fame also sprang from the presence of a large Scandinavian migration to North America in response to poverty and a shortage of agricultural land. Between 1861 and 1881, 150,000 Swedes travelled to the United States, 100,000 of whom came in just five years, between 1868 and 1873. Chicago, at the time of Lagerlöf’s prize was the second-largest Swedish city in the world. It was not just a Swedish issue, the mass migrations across the world in the late nineteenth century were the largest in history, and redefined the nations and empires that would clash in the twentieth century.

1910 Paul von Heyse (1830 – 1914, Germany)

When Paul von Heyse, another German, won the Prize in 1910, the judges compared him to the incomparable German genius Goethe. The commendation celebrated how von Heyse displayed “consummate artistry, permeated with idealism, which he has demonstrated during his long productive career as a lyric poet, dramatist, novelist and writer of world-renowned short stories.”

Today many might know Goethe, but few remember von Heyse. His reputation endures for novellas, short stories and his Italian translations.

He lived a quiet, productive literary life in Munich, and was an entrepreneur of literary societies and his own literary reputation. But I have struggled to connect with his work, or to find many translations.

There are some stories you can listen to at Librivox , or read here. His major novel, In paradise can be obtained on Amazon. His lyrics however, set to music by the great German Romantic composers, are perhaps his most enduring legacy. This short lyric in translation I found in a collection of German lyrics, though I do not know them in German.

The Scarecrow.

A monk stands in the meadow -

Or rather his old clothes,

The cowl and garments flutter

Whene'er the tempest blows.

Now, thinks the pious peasant,

Our grain we'll sure protect,

The sparrows will respect it

In holiness bedeckt.

The sparrows think the friar

Example precious gives;

He neither sows nor harvests.

Yet God grants whence he lives.

Paul Heyse

He was a Nobel medallist from a dying pre-modernist culture. He was also the oldest Laureate ever to win the Prize. He did not survive to see the death of the belle époque in the hellscape of World War One. His literary fame died in the world that followed.

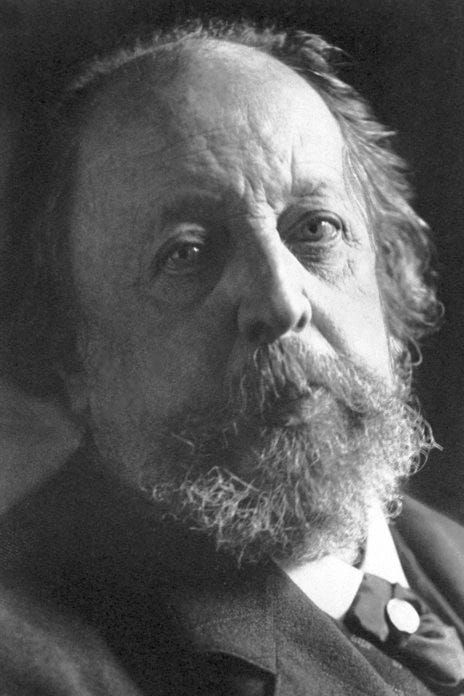

1911 Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949, Belgium)

Maurice Maeterlinck was a Belgian playwright, poet, and essayist. He was Flemish but wrote in French.

He was the first Laureate to represent the aesthetic transformations of modernism. He was a Symbolist, that movement the first Nobel winner Prudhomme reviled. He was also the earliest Laureate who would live to survive the Second World War. His story is in some ways tragic.

His main early work was Symbolist, mystical, and metaphysical. Before the Great War he was attracted to socialist causes which he advocated in his polished epigrammatic essays. His non-Christian mysticism, criticisms of organised religion, and political views provoked the Catholic Church to placed him on its index of banned books in 1914.

He made his reputation as a dramatist, but in the early twentieth century he suffered a period of depression. He worked his way out of that depression by writing the essay describing the characteristics of flowers, "The Intelligence of Flowers" (1906). It was translated anew in 2007 and bears similarities to Sebald’s prose non-fiction, spinning out from quasi-scientific observations to reflections on the dilemmas of modern life.

These instances might be multiplied indefinitely; every flower has its idea, its system, its acquired experience which it turns to advantage. When we examine closely their little inventions, their diverse methods, we are reminded of those captivating exhibitions of machine-tools, of machines for making machinery, in which the mechanical genius of man reveals all its resources. But our mechanical genius dates from yesterday, whereas floral mechanism has been at work for thousands of years.

Like this whole generation of Europeans, he was caught up in the militant nationalist enthusiasms of World War One. He sought to enlist but was denied access to the slaughterhouse because of his age. Instead, he wrote patriotic literature for the French Belgian cause. After 1920 he wrote little for the theatre, but focussed on occultism, ethics, and natural history. In 1940 he fled Belgium to the USA via Lisbon to escape the marching Germans. He did not like America and returned to Nice after the war.

He was made a Count by the Belgian king in 1932, by the same monarchy that practised the colonial horrors portrayed in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Some critics from Belgium’s African colonies claimed that after the Nobel Prize he had fallen into plagiarism in works that claimed a knowledge of Africa. The claims hold up.

Yet he remains an eminently quotable author of aphorisms. One of the most moving of these aphorisms is:

“For it is our most secret desire that governs and dominates all. If your eyes look for nothing but evil, you will always see evil triumphant; but if you have learned to let your glance rest on sincerity, simpleness, truth, you will ever discover, deep down in all things, the silent overpowering victory of that which you love.”

― Maurice Maeterlinck, Wisdom and Destiny

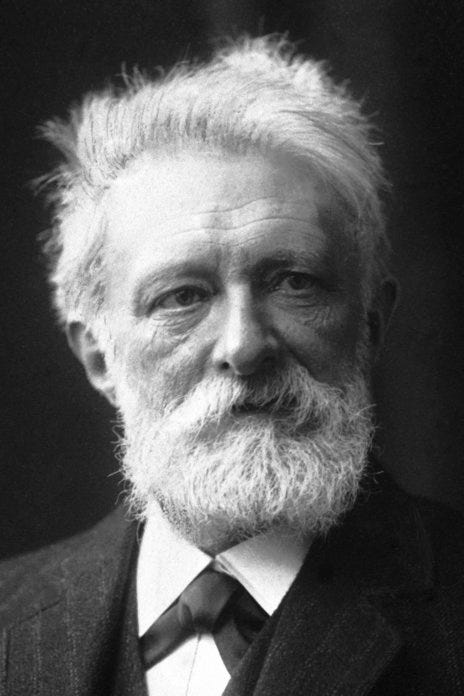

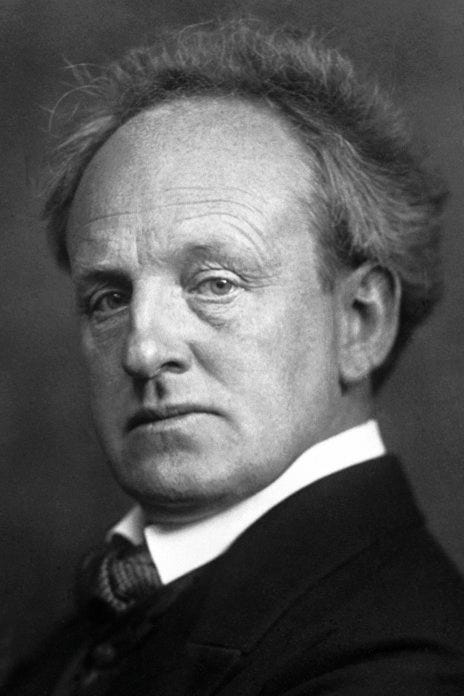

1912 Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946, Germany)

Hauptman was another German winner of the Prize before 1914, when German culture was, despite the mockery of the British, a leading light of the world. But his career after the Prize represented, and was tainted by, the tragedy of German nationalism and the cowardice of the famed artist.

Hauptman himself seemed to have a premonition of his own dangerous moral crisis in his 1911 novel, Atlantis.

“The lives of unusual men from decade to decade, it seems, enter dangerous crises, in which one of two things takes place; either the morbid matter that has been accumulating is thrown off, or the organism succumbs: to it in actual material death, or in spiritual death. ' One of the most important and, to the observer, most remarkable of these crises occurs in the early thirties \ or forties, rarely before thirty; in fact, more frequently not until thirty-five and later. It is the great trial balance of life, which one would rather defer as long as is expedient than make prematurely”

Hauptman, Atlantis pp 10-11

This novel about a disaster on a cruise ship itself was a premonition of the Titanic disaster of the next year.

Hauptman established his reputation as a playwright who wrote Naturalist plays. His 1889 play Before Sunrise caused a famous scandal by its frank depictions of alcoholism and sexuality. This play was translated by James Joyce, who adopted aspects of naturalism in his early fiction. You can watch a glimpse of a 2019 German performance of this play here.

Hauptmann became known as a social democratic poet, including then progressive social reform ideas including temperance and eugenics. He was a founding member of the eugenics organization, the German Society for Racial Hygiene, in 1905. Before Sunrise was a portrayal of hereditary alcoholism, one of the social evils progressive eugenicists such as Hauptmann sought to expunge.

The Kaiser disliked this social democratic poet, but like so many social democrats in August 1914 Hauptmann submitted to the wave of fervour for a war to defend civilization. He signed a letter of support for the German cause in World War One. It may seem odd to see these intellectuals submit to crowd sentiment, but have we not witnessed many similar crazes since? Defeat in the war, however, disillusioned him. In 1918 he fled to a pacificist colony in Locarno, and then supported the new Weimar Republic.

By the Weimar years, the Nobel Laureate had been spoiled by success. He lived the high life on his fame and wealth, but produced little worthy work. He wrote mediocre scripts for films and serials, and became something of a literary hack. But the Prize had cemented his reputation across the Atlantic as the representative of German literature. At home, he was mocked. Thomas Mann pilloried his character traits in the fictional character, Mynheer Peeperkorn, in The Magic Mountain. The great Marxist, modernist critic, György Lukács, described him as the representative poet of bourgeois Germany.

In 1933 Hauptmann signed the loyalty oath to Hitler’s regime, and some reports claim he applied to join the Nazi party. He would certainly later be celebrated by the Nazis. He was placed on a special list of protected artists, who were exempted from military mobilization in the downfall years of the war. In 1945 lived in Silesia, which would became part of Poland, but was not allowed to leave by the Soviet Union, despite some pleas by literature buffs in USSR. He died a tragic figure, consumed by his own and his culture’s death-wish.

He had witnessed, at a safe distance the fire-bombing of Dresden, of which he wrote:

"Whoever had forgotten how to cry learned again at the destruction of Dresden. I stand at the end of my life and envy my dead comrades, who were spared this experience.”

Hauptmann’s story is of the cowardice of writers, the ruin of talent, and the tragedy of national imperialism.

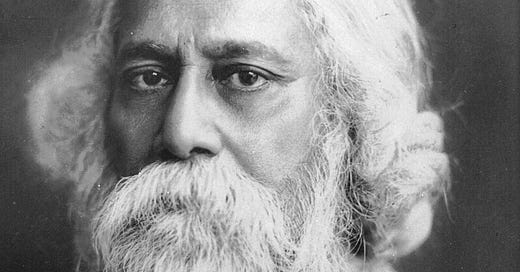

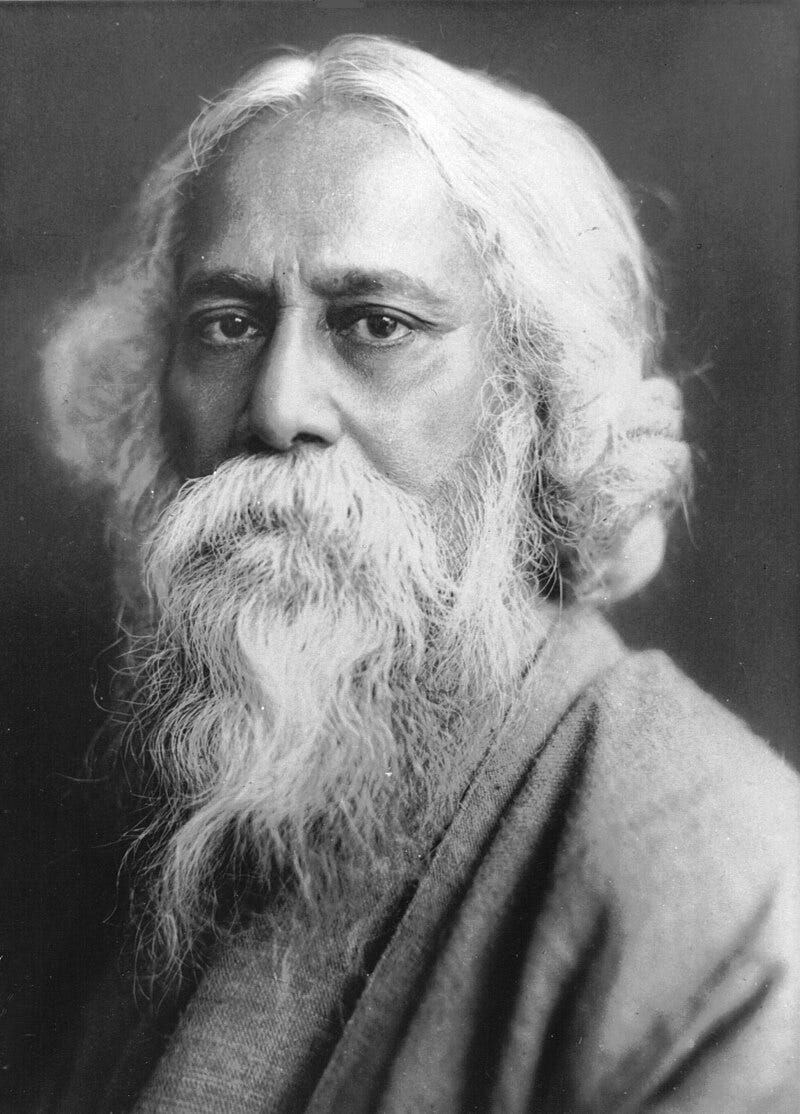

1913 Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941, India)

By contrast to most of the winners since 1901, Rabindranath Tagore stood courageously against nationalism and against empire. He was the first non-European and first Asian to win the prize. An Asian would not win again until the late 1960s.

I have written about Tagore in previous essays and read from Tagore’s essays too. So I will not expand on those earlier discussions. But let me offer you one of his famous songs, which are still sung in Bengal.

Nabo Anande Jago

Delightfully wakeup with the promising rays of sunlight

To a life beautiful as the white colour, bright with love and clean.

(Look at) the fountain of life evolves, songs of euphoria usher hopes,

Serene breeze carries the scent of heavenly flowers.

Better yet you can listen to this and other famous Tagore songs here.

Of all these seven writers, Rabindranath Tagore is the most enduring, and still the most famous, if we open our eyes to the view from the East.

Thank you for sharing your work and thoughts. Love your continuity in following the (evolution?) changing of zeitgeist recognition over time of these committee picked award recipients.

Loved this article. Saw it on Sarah’s cohort. I live in Canberra and would like to get in touch with you Jeff. I will DM you my email and phone number.