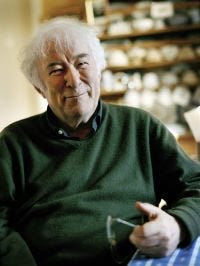

Seamus Heaney, Nobel Prize for Literature 1995

Poetry as a path from troubles through Beowulf to peace

In 1989 the Berlin War fell. The post-1945 partition of Europe ended. In North America, Francis Fukuyama declared the end of history. But beneath the triumphant surface, deeper conflicts simmered. Seamus Heaney wrote poetry to lead us from those troubles. So too did the Nobel Laureates between 1989 and 1995.

The pain of the Spanish Civil War and Franco dictatorship lingered in Spain. Apartheid fizzled in South Africa. The USA struggled to own up to its legacy of segregation and slavery, its dominion over Mexico, and its subjection of Japan. The Troubles in Ireland made bombings in County Derry into monthly global news.

The Swedish Academy dispelled the illusion of the unipolar moment. It honoured with the Nobel Prize for Literature witnesses of the post-1945 world’s hidden suffering.

My favourite writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature between 1989 and 1995 was Seamus Heaney, the great Irish poet.

He was a compassionate witness to a society divided by the Troubles. He was also the translator of the Old Anglo-Saxon English poem, Beowulf.

Before we get into Heaney, last week I ran a poll on the style of these posts that would suit you as a reader better.

The results are in and clear. Over 80 per cent of readers wanted me to focus on one writer per weekly post, even if the series extends into 2025.

So that is what I will do. But I will still reference every winner and provide brief profiles of them on my YouTube video summaries. I will come back to some of the writers not featured in the run-up to the 2024 Prize announcement in posts during 2025.

The 2024 Nobel Prize for Literature will be announced on 10 October, just five weeks away! From next week I will also provide snapshots of some of the writers who might win the prize in 2024.

You can watch this week’s video summary of the seven winners here, from Sunday night. It covers:

1989 Camilo José Cela (1916–2002) Spain

1990 Octavio Paz (1914–1998) Mexico

1991 Nadine Gordimer (1923–2014) South Africa

1992 Derek Walcott (1930–2017) St Lucia

1993 Toni Morrison (1931–2019) USA

1994 Kenzaburō Ōe (b. 1935-2023) Japan

1995 Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) Ireland

My focus this week is Seamus Heaney, the great compassionate witness of the tragedy of Ireland’s civil war of decolonization, the Troubles.

Voiceover is available. Please enjoy it while you go for a walk and take some time away from a screen.

Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) Ireland

Heaney won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995 "for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past." He is admired by poets, critics, and the general reader. He was especially beloved in Ireland. On his 70th birthday in 2009, the national broadcaster aired twelve hours of Heaney’s recorded performances of his poetry.

Such an honour did not come only because Heaney was a great poet. He was loved because he was a humble witness of the decades of tragedy in Ireland, known as the Troubles. From the late 1960s to 1998 the Irish, and to a lesser extent British, were tormented by a long, simmering, low level war over the status of Northern Ireland. This territory was carved out by the British Empire after most of the island of Ireland became an independent state in 1922. Blood had been spilled earlier. There was violence and terror during the long struggle over Home Rule. There was the violence of the 1916 Easter Rebellion – “a terrible new beauty” - commemorated in the poem by 1923 Nobel Laureate, W.B. Yeats. But by the 1960s the separatist Sinn Féin party had a violent, paramilitary wing, the Irish Republican Army. It was the rebel force who fought the British and the local Northern Irish British loyalists, organised themselves into a paramilitary force as the Ulster Volunteer Force.

The conflict had overlays and undercurrents. There were religious differences between Protestant and Catholic, rival local cultures, class tensions, sectarian hatreds, ethno-nationalist sentiments, revolutionary politics, and resentments against Britain’s centuries long imperial adventure in Ireland. The conflict drove families and neighbours apart. Heaney witnessed and experienced all the rending of the human Irish heart.

His collections Wintering Out (1973) and North (1975) imagined the Troubles within Ireland’s deeper history. Violence, hatreds of out-groups, and civil strife are part of the long human past, as Richard Overy showed in Why War? (see my review article, “The Psychology of Conflict”). Some critics and partisans chided Heaney for not taking a side. The anger of the Troubles drove these critics to claim Heaney was an apologist and mythologizer. In fact, he was a compassionate poet who engaged in deep reflections on history and its echoes in our tragedies.

Heaney himself was born and raised as a Catholic in the Protestant County Derry, Northern Ireland. He knew the troubles in his bones and his heart. He came from poor rural Northern Ireland, and as he once described himself "emerged from a hidden, a buried life and entered the realm of education." The civility of that new life was threatened by the violence of the troubles, but Heaney chose to see the roots or its consequences on the people of every side and family. He wrote elegies for friends and acquaintances who died. He interpreted the unrest against figures of Irish historical mythology, its past of Viking settlement, and even the violence marked on the body of the men preserved in the peat bogs of Europe, discovered during these times, known as Tollund Man.

In his collection, North, the poem, ‘Funeral Rites’ describes the common experience of these years in Ireland, and in any country wracked by civil war. It begins:

I shouldered a kind of manhood

Stepping in to lift the coffins

Of dead relations.

(Heaney, New and Selected Poems 1966-1987, pp. 52)

It describes the uneasy comfort offered by the funeral processions, that became both acts of grief and marches of protest in the Troubles.

Now as news comes in

Of each neighbourly murder

We pine for ceremony, customary rhythms:

The temperate footsteps

of a cortège, winding past

Each blinded home.

(Heaney, New and Selected Poems 1966-1987, pp. 53)

Its closing stanzas evoke the bitterness of feuding and the salt of the funeral rite thrown over the shoulders of warriors unreconciled to peace.

When they have put the stone

Back in its mouth

We will drive north again

Past Strang and Carling fjords,

The cud of memory

Allayed for once, arbitration

Of the feud placated,

Imagining those under the hill

Disposed like Gunnar

Who lay beautiful

Inside his burial mound

Though dead by violence

And unavenged.”

(Heaney, New and Selected Poems 1966-1987, pp. 54-55)

Most of the poetry by Heaney that I have read comes from the years of the unresolved Troubles, collected in New and Selected Poems 1966-1987. In preparing this piece, I learned there was a shift in style and material in his later works. In Seeing Things (1991) he takes a more spiritual, less concrete approach. The Spirit Level (1996) explored humanism, politics, and nature. His second collected poems, Opened Ground: Selected Poems, 1966-1996 (1998), is now on my list to collect. In Electric Light (2001), Heaney wrote poems of memory, elegy, and the pastoral tradition, including not just Anglo-Irish but classical Roman references. District and Circle (2006) was his last collection. There is much Heaney poetry to read, and some fine essays including The Government of the Tongue (1996).

Heaney gave the modern world another great gift as well as his own poetry. In 2000 he translated the Old Anglo-Saxon English poem, Beowulf. Beowulf is a heroic elegiac poem composed sometime between 600 and 1000 CE. It was written by a Christian Anglo-Saxon poet, who looked back, with both distance and generosity, at the lost culture of his Germanic, Scandinavian, and pagan forebears. Like Benjamin’s Angel of History, this forgotten unnamed poet sought to preserve stories of the past from the flames, while knowing time blew him into the future.

Heaney performed a similar graceful act of rescue of the culture he felt connected to. He preserved and renewed the poem by translation into modern English, while miraculously preserving the skaldic rhyming forms of the old language.

A section from near the end of the poem gives an insight into Heaney’s poetic skill. You hear the internal rhymes, assonance, and alliteration in each line. You sense both Heaney and the lost poetic tradition’s keen insight into civil war. It describes the funeral of Beowulf, after the warrior had been killed after many heroic struggles on behalf of his people, when he is thrown upon a funeral pyre. Then, a voice of a woman strikes a note, which differs from the male boasts of battle and wails for a dead hero. It is a lament, sometimes known as a keening.

A Geat woman too sang out in grief;

With hair bound up, she unburdened herself

Of her worst fears, a wild litany

Of nightmare and lament: her nation invaded,

Enemies on the rampage, bodies in piles,

Slavery and abasement. Heaven swallowed the smoke.

P. 208 illustrated edition

Beowulf merits a whole other post. The poem itself was saved—literally—from the flames by a librarian leaping from the window of a burning archive. I tell this story in this podcast (which you can listen to on Substack or your pod player). It includes a short audio clip of Heaney himself reading from Beowulf in both the original language and his translation. It also includes a guest appearance by my daughter, Freya, who is, like my son Isaac, both subscriber and contributor to the Burning Archive. Thank you, Freya and Isaac.

The preface to Heaney’s translation of Beowulf tells the story of how he came to appreciate the language, and how it represented Heaney’s own emergence from the Troubles.

“Joseph Brodsky once said that poets’ biographies are present in the sounds they make and I suppose all I am saying is that I consider Beowulf to be part of my voice-right. And yet to persuade myself that I was born into its language and that its language was born into me took a while: for somebody who grew up in the political and cultural conditions of Lord Brookeborough’s Northern Ireland, it could hardly have been otherwise.”

It was a long struggle for him to overcome the “cultural and ideological frame” of his Irish nationalist background. But, after decades, he found in his own mind a way to find peace between his cultural traditions, when peace broke out after the Good Friday settlement in 1998.

“I tended to conceive of English and Irish as adversarial tongues, as either / or conditions rather than as both / ands, and this was the attitude which for a long time hampered the development of a more confident and creative way of dealing with the whole vexed question - the question, that is, of the relationship between nationality, language, history and literary tradition in Ireland.”

Pluralism, not the binaries of hate and the Troubles, proved to be Heaney’s path to peace. In The Government of the Tongue, he celebrated how poetry was a form of concentrated thought, that “functions not as distraction but as pure concentration, a focus where our power to concentrate is concentrated back on ourselves.” p. 108

His closing paragraph of that essay reminds us that poets are not the unacknowledged legislators of the world. They best help us govern our tongues when they defend pluralism and peace.

“Poetry is more a threshold than a path, one constantly departed from, at which reader and writer undergo in their different ways the experience of being at the same time summoned and released.” p. 108

If you want to read more Heaney there is a free selection and introduction to his poems here at the Poetry Foundation.

I found this recent documentary, Seamus Heaney: And the Music of What Happens free on YouTube.

Please enjoy.

Thank you for supporting the Burning Archive by reading and subscribing.

I would love you to share this post with others - to help spread the word of how my writing can help us live in tune with a changing world.

If you would like to be a patron of the arts, you can make a one-off contribution to the Burning Archive here.

Thank you, all.

By reading my work, we together look for the threshold, rather than the path.

Jeff.

I think you made the right decision. This was a fabulous post, the Arena programme had me in tears, not a bad thing. I loved the depth, breadth and the detail of this post. You even gave a bibliography. The only thing was , I was so enthused I bought several of Heaney' books, more than I should, but hey you can't have too much good history and poetry. So hou know a good biography of Heaney. The Arena programme was so fascinating I want more about the life behind the poetry. I read the Substack, are notes and watched the links I the afternoon. I bought several collections on Kindle, and had a beautiful evening reading the poems. I also bought the book of essays you mentioned. I think the poems will be upgraded to actual books soon. Thanks for a fascinating and inspirational day, Jeff.