Forgotten, Famous and Favourite Nobel Literature Prize Winners (1915-21)

120 Nobels Challenge * WEEK 3 * (1922-28): scars of World War One

What can you learn about world literature and world history through the Nobel Prize for Literature?

Since 1901, 120 writers have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Some are forgotten. Many remain famous. A few became notorious for reasons that might surprise you and change your understanding of modern history.

Until October, dear reader, you can participate in the Burning Archive’s first booklover’s challenge. Over 120 days, I will read every single winner of the Nobel Prize. I will share what I find and invite you to read those writers who prompt your empathy. Please join me on this pilgrimage walk through the cultural history of the modern world.

This week, we read the winners from 1915 to 1921. The Nobel Literature Prize was interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1914, and scarred by the Great War in these seven years. Two Laureates remain famous or notorious from those years. They took opposite sides in the war that was to come in the 1930s, but both opposed the Anglo-Americans. Who were they?

Let me introduce seven Nobels scarred by war.

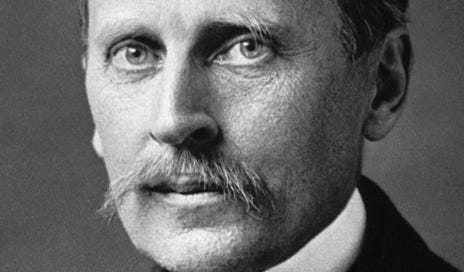

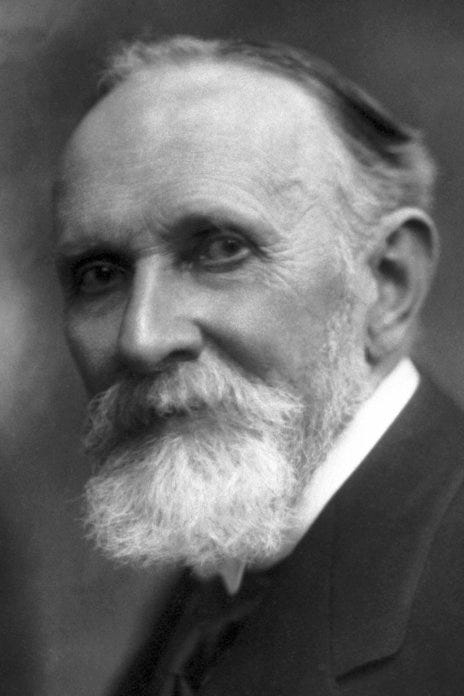

1915 Romain Rolland (1866–1944) France

Romain Rolland was a novelist, essayist, art historian, mystic and supporter of the international struggle for peace through the Soviet Union.

He trained as an historian, wrote his PhD on opera history, then taught music history. Teaching did not suit his personality, and he began to write. He first wrote plays, not for the elite at the opera, but for the workers in popular theatre. Then he began his early modernist novels.

He conceived an alter ego, a young musician, as the hero of his 10-volume novel sequence, Jean-Christophe (1904–1912). Its hero responded to failures and social conflicts and growing cultural chauvinism in pre-1914 Europe. This masterpiece won him the Nobel Prize.

Rolland described its literary structure as a river, not an artifice. It was loosely structured as a flow of ideas and commentary, not a traditional plot. He used the book to narrate his social criticisms, which he had dramatised in popular theatre. He recalled when he began to write the book:

"I was isolated: like so many others in France I was stifling in a world morally inimical to me: I wanted air: I wanted to react against an unhealthy civilization, against ideas corrupted by a sham élite: I wanted to say to them: 'You lie! You do not represent France!'

I enjoyed my sample from volume one, and you can explore it here or listen to a Libri Vox recording here.

Rolland criticised European society as a humanist. He believed culture could overcome religious bonds and national borders. He practised dialogue with cultures beyond Europe. Rolland embraced the Indian ideas of Tagore (the 1913 Laureate) and Gandhi, and resisted the surge of Western nationalism in 1914.

World War One shocked him. It was fitting that the Academy of neutral Sweden awarded the 1915 Prize to this advocate of pacifist internationalism. Rolland had fled the newly militant France to neutral Switzerland in 1914. There he published Au-dessus de la mêlée (Above the Battle) in 1915 as a protest against the war. After the war, in 1924, his book on Gandhi boosted the reputation of the non-violent opponent of the British empire.

Rolland’s internationalist sympathies drew him to the Soviet Union in the era of the Popular Front in France and rising fascism in Europe. He met Stalin in 1935 through the graces of the great Russian man of letters of the Bolshevik regime, Maxim Gorky. He became France’s de facto cultural ambassador to the Soviet Union, which was not then abhorred like in the post-1945 West. Indeed, Stefan Zweig honoured Rolland as the “moral consciousness of Europe”. Others however questioned his blindness to the years of the Yezhovian terror.

Rolland became a European Tagore. The first Asian Laureate’s great end-of-life essay, Crisis in Civilization (1941), written in the depths of World War II, may have expressed Rolland’s views on the social progress of the internationalist Soviet Union in contrast to the old Western European nationalist empires.

Like Tagore, Rolland sought to immerse himself in all the currents of history and streams of civilizations. In his great anti-war tract, he wrote

“The true man of culture is not he who makes of himself and his ideal the centre of the universe, but who looking around him sees, as in the sky the stream of the Milky Way, thousands of little flames which flow with his own; and who seeks neither to absorb them nor to impose upon them his own course, but to give himself the religious persuasion of their value and of the common source of the fire by which all alike are fed.”

― Romain Rolland, Au-dessus de la mêlée

Rolland believed in what I call the infinite conversation. His spirit lives on in the flames of the Burning Archive.

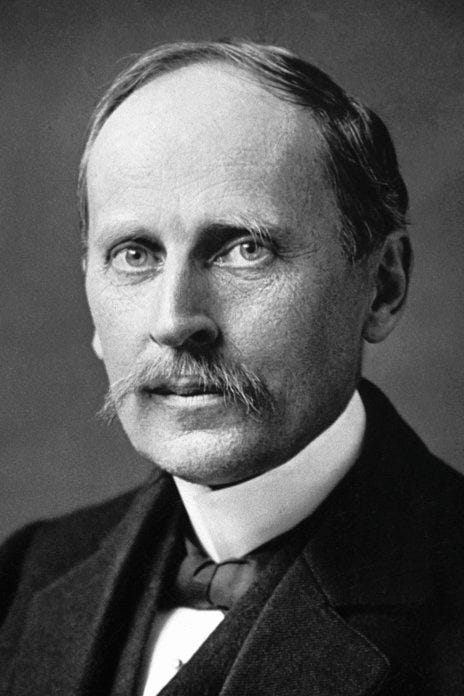

1916 Verner von Heidenstam (1859–1940), Sweden

The following year, horrified by inglorious death in the trenches, the Swedish Academy turned its back on the belligerents of Europe, and chose a conservative poet and novelist from Sweden for the Prize.

Verner von Heidenstam loved Swedish history, and expressed conservative nationalist thought in Sweden. His aphorism epitomised his outlook: “You smile, my people, but with stiff moves, and sing, but without hope.”

He opposed the crude modern world ruining art. He defended his conservative strain of literature in a quarrel with the great dramatist, Strindberg, who today in the Anglophone world may be better known. He wrote lots and in many forms. But his texts are not easy to obtain in English translation. You can read his works in Swedish, and some automatically generated English translations, here.

One brief stanza of a poem, “From the Thoughts of Loneliness”, caught my eye.

I have been longing for home for eight long years.

In the sleep itself, I have felt the longing.

I long for home. I long for where I go

--but not to humans! I long for the ground,

I long for the stones, where children I played

He also wrote stories. The Queen of the Marauders reflected his pride in Swedish history. It looked back on Sweden’s 17th and early 18th century era of glorious military expansion, and its wars against Russia and Peter the Great. The story begins with ghoulish images of the ‘Asiatic horde’ of the Russians.

“The tocsin in the church tower at Narva had ceased. In a breach of the battered rampart lay the fallen Swedish heroes, over whose despoiled and naked bodies the Russians stormed into the city with wild cries. Some Cossacks, who had sewed a live cat into the belly of an inn-keeper, were still laughing in a circle around their victim, but the gigantic Peter Alexievitch, the czar, soon burst his way through the midst of the throng on street and courtyard and cut down his own men to check their misdeeds.”

Verner von Heidenstam was neither the first (Sienkiewicz 1905) nor the last anti-Russian to win a Nobel Prize.

1917 Karl Adolph Gjellerup (1857–1919), Denmark

Gjellerup was a Danish poet and novelist. The Danes, however, resented that he largely lived in and ‘identified with’ Germany, in modern parlance. His prize was shared in 1917 with another Dane, who stood on the other side of the war that was still raging in Europe.

Gjellerup was the third early modernist Laureate, after Maeterlinck’s symbolism and Rolland’s narrative experiments. Gjellerup’s innovations were modest, however, compared to the golden age of modernism after 1918. He is largely forgotten today.

Like Rolland, he was influenced by Buddhism and Eastern cultures. It may seem orientalist to some minds, but shows the currents of cultural history never flow in a single direction. His novel Pilgrim Kamanita retold the story of the Buddha for a Western audience. Read it here.

1917 Henrik Pontoppidan (1857-1943), Denmark

Pontoppidan was the fellow Dane who shared the Prize in 1917. He was a novelist who kept his distance from the political poles of conservative and socialist to observe the deeper social rumbling that would tear the European and American social fabrics in the early twentieth century.

His modernist novels portrayed those tears and rumbles in the tradition of Balzac and Zola. In Lykke-Per (Lucky Per) a gifted man tried to transcend the limits of his society, like a Nietzschean übermensch, but failed. His ambition destroyed him, and by the end of the novel he gave up his career to solitude. In 2018 it was translated anew by Paul Larkin as A Fortunate Man. The translator described the novel’s enduring relevance here.

In The Realm of the Dead Pontoppidan portrayed the social tensions in Denmark after the apparent victory of democracy in 1901. It was a society in which, to paraphrase one critic, political ideals mouldered, capitalism marched on, and the press and art were prostituted by early consumerist society; imagine the TV series Babylon Berlin set two decades earlier in Copenhagen. His last novel, Man’s Heaven, described the bleak crisis of a Danish intellectual at the time of the outbreak of World War I. It was a tragic self-portrait.

Leif Sjoberg, a Danish literary critic, summarised the legacy of this lasting Danish modernist, who Anglophone readers have little access to.

He is a major and lasting figure within the belles lettres of his own country, has received much recognition abroad, and has even been widely read in translation, while nevertheless remaining pretty much an unknown quantity for a large and important segment of the world of literature: readers of English.

In 1927, Thomas Mann, on the eve of his own Nobel, honoured Pontoppidan on his seventieth birthday with this tribute.

The author of Lykke-Per is a born epic poet and as a critic of life and society enjoys European stature. A true conservative, who in a breathless world has preserved the grand style in the novel. A true revolutionary, who in his prose above all has kept its power to pass judgments in view. With the winning and delightful severity that is the secret of art, he has judged the times and, like the true poet which he is, pointed toward a purer humanity.

I have added him to my long reading list of writers to explore next year.

1919 Carl Spitteler (1845–1924), Switzerland

No prize was awarded in 1918 as much of Europe descended into turmoil. In 1919, ideals returned. Carl Spitteler was a Swiss poet, and grandee of classical European culture, who was scarred by World War I and found his way into the unconscious of the West.

By the time of the war, he was a leading intellectual figure of classical belle epoque Europe. In neutral Switzerland he found himself in a society divided between people who identified with either combatant, France or Germany. Spitteler opposed the pro-German attitude of the Swiss German-speaking majority in the Great War.

His major poem is Olympian Spring, an epic verse poem, which you can read in German here. This work alone won him the Nobel Prize, but I struggled to find an English translation. In 1952 this review described Spitteler’s poem as a neglected masterpiece. In the Anglophone world, he has fallen from neglect to oblivion.

This bibliophile reported that only one English translation of Spitteler’s poems was ever published, in 1928. Thanks to this fellow scholar of the internet, you can read this short Spitteler poem, “Another Waking.”

From the nightmare world of dream

I awakened with a scream.

Chime of bells and song of bird

Deep in budding woods I heard;

Broke the friendly golden day,

Fear and anguish fled away.

Come there will a time for me

When no day shall set me free,

When my only comfort shall

Lie in dreams fantastical,

When from darkling night I fain

Never would be waked again.

Despite neglect, Spitteler‘s spirit lives on in the collective unconscious of Western culture. His poem, Prometheus and Epimetheus (1881), was interpreted by Carl Gustav Jung, the great Swiss psychoanalyst, in Psychological Types. Jung indeed later claimed his idea of the archetype of the Anima was based upon what his fellow Swiss intellectual, Spitteler, had described to him as 'My Lady Soul'.

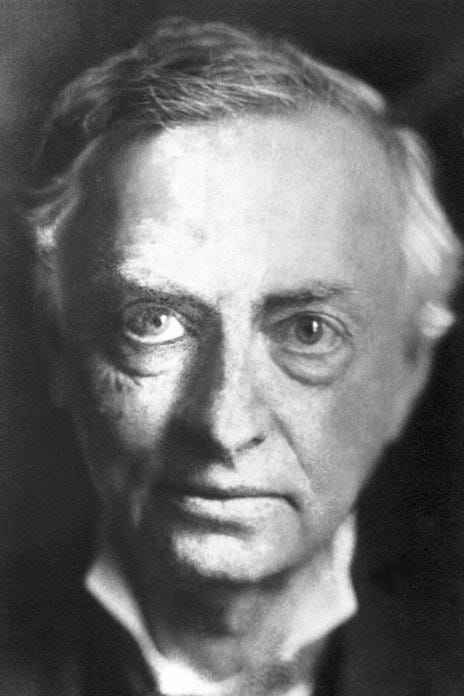

1920 Knut Hamsun (1859–1952) Norway

The second major figure, after Rolland, from these wartime Nobels was the Norwegian, Knut Hamsun. He was prolific. He published a score of novels, a collection of poetry, short stories, plays, a travelogue, non-fiction, and essays. But his work is stained by notoriety.

Before World War II, he was recognised as a fountainhead of literary modernism. His style used techniques of stream of consciousness and interior monologue, which became hallmarks of literary modernism. Isaac Bashevis Singer, who would win the Nobel in 1978, called Hamsun:

the father of the modern school of literature in his every aspect—his subjectiveness, his fragmentariness, his use of flashbacks, his lyricism. The whole modern school of fiction in the twentieth century stems from Hamsun.

His lapidary style influenced Beckett and Hemingway. You might hear overtones of Beckett’s Malone in this line from Ringen sluttet (The ring stopped): “But things worked out. Everything works out. Though sometimes they work out sideways.”

He expressed a neo-romantic revolt against progress and a new realist appreciation of nature in a technological world. The connection between characters and nature is exemplified in the novels, Pan, A Wanderer Plays on Muted Strings, and the epic Growth of the Soil, which secured him the Nobel Prize. At the start of that novel, Hamsun evoked the weakness of technological man before the vastness of the earth and history:

The long, long road over the moors and up into the forest—who trod it into being first of all? Man, a human being, the first that came here. There was no path before he came. Afterward, some beast or other, following the faint tracks over marsh and moorland, wearing them deeper; after these again some Lapp gained scent of the path, and took that way from field to field, looking to his reindeer. Thus was made the road through the great Almenning—the common tracts without an owner; no-man's-land.

But like many modernist writers of this era - Yeats, Pound, Eliot and more - Hamsun was drawn to authoritarian and racialist politics. There were social conditions that drove these choices in a Europe divided socially, made fragilely democratic in its politics, and threatened by the Red Bolshevik East. But it was a sense of cultural grievance that led Hamsum to choose the wrong empire in the 1930’s, and end up on the wrong side of history.

His resentment drove him mad politically. Hamsun hated the English, in part due to the treatment of Norway during World War I. He supported Nazi Germany and its collaborators in Norway, headed by Vidkun Quisling. The Norwegian writer even met with the dictator, Hitler, during the German occupation of Norway.

He believed in the pan-Germanic cause of the Reich to push back English hegemony. Hamsun wrote, "the Germans are fighting for us, and now are crushing England's tyranny over us and all neutrals.” His support for a pan-Germanic Norway may have been similar to that of the 1903 Laureate, Bjørnson; but Hamsun let politics go to his writer’s head, and betrayed his country in fury. His support for the Quisling regime led to a charge of treason after the war.

He was not convicted. He was sentenced like Ezra Pound, that great modernist who supported Mussolini. Pound was charged with treason, impounded in Pisa, tried in America, and spared the death sentence on the grounds of insanity. Hamsun was similarly excused, but he protested against the designation. By then in his 80’s, Hamsun was undone by grievance.

Despite years of shame about his collaboration with Nazi Germany, Hamsun's works remain popular in Norway. In 2009, a Norwegian biographer stated, "We can’t help loving him, though we have hated him all these years ... That’s our Hamsun trauma. He’s a ghost that won’t stay in the grave."

For Hamsun, biography, art, and politics combined in a mythological theme. The theme was central to his novels, his personal tragedy, and Norse mythology since Odin. Hamsun was the perpetual wanderer.

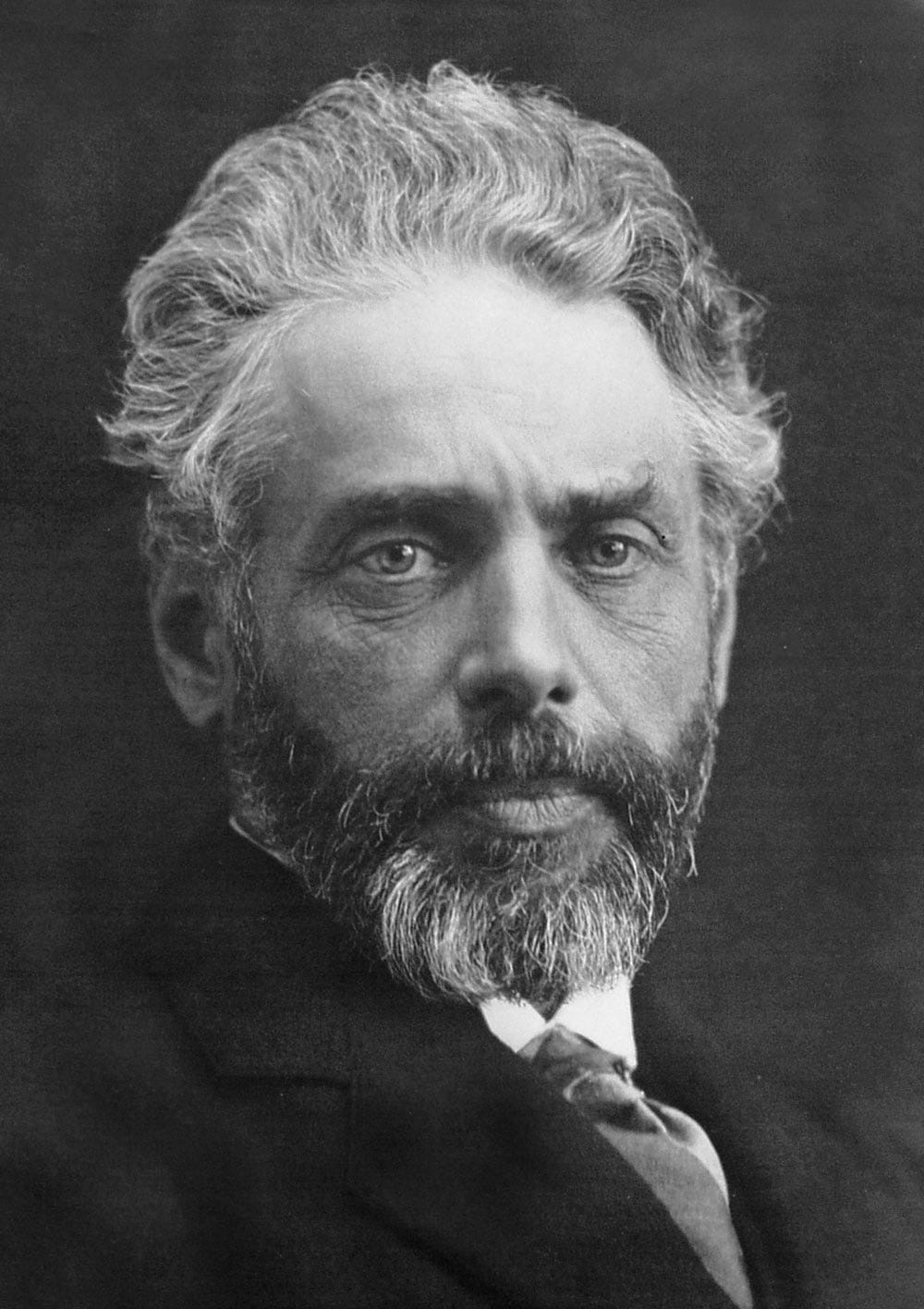

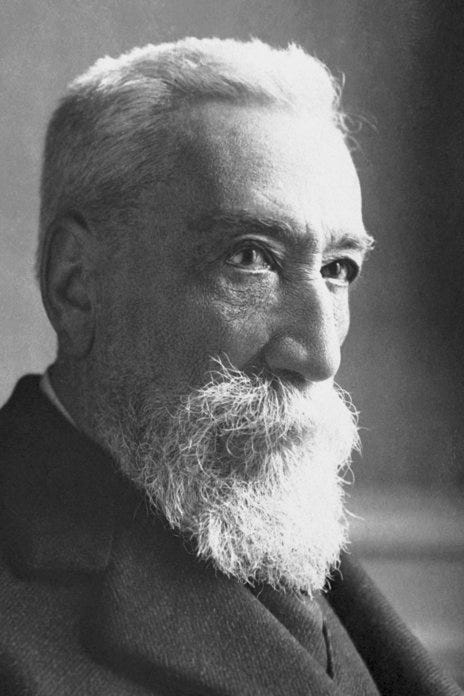

1921 Anatole France (1844-1924), France

Anatole France was the grand old man of French letters. He won the prize in 1921, by which time Marcel Proust had immortalised strands of France in the character of the great writer, Bergotte, in In Search of Lost Time.

France’s early work mocked the spiritualism, which, we have seen, was common among earlier Laureates and turn-of-the-century elites around the world, even a Prime Minister of remote Australia. France supported Dreyfus in the great Assange-like affair that ran like a scarlet thread through Proust’s novel. He wrote a series of famed, polished novels. But compared to Proust’s novels, the incomplete remembrances of France’s neurotic portraitist, they are lost to time

L'Île des Pingouins (Penguin Island) (1908) satirized human nature by depicting the transformation of penguins into humans. The Gods Are Athirst (Les dieux ont soif, 1912) was set in Paris during the French Revolution, but reflected on the threats of mass society in France’s time. It worked through the traumas of France’s failed revolutions in 1848 and 1870, and expressed the growing fear of political and ideological fanaticism and the madness of the crowd documented in the work of Gustave Le Bon. The Revolt of the Angels (La Revolte des Anges, 1914) presented a modern allegory of Satan’s Fall, based on the Christian understanding of the War in Heaven. France wrote modern fables about fallen modern humanity.

Yet France sympathised with leftist politics, and, in 1917, the aged liberal supported the 1917 Russian Revolution. Paradoxically, he also defended the institution of monarchy as more inclined to peace than bourgeois democracy. He had seen the irrational crowds lining up for glorious death in trenches in 1914. He was scarred by the populist militarism of World War I. His political views earned him a place, like Maeterlinck, on the Catholic index of banned books.

I find his novels hard to connect with today, but his aphorisms endure.

“We chase dreams and embrace shadows.”

“Stupidity is far more dangerous than evil, for evil takes a break from time to time, stupidity does not.”

“It is the certainty that they possess the truth that makes men cruel.”

In all these epigrams, he showed the worldly wisdom of Proust’s Bergotte.