Slow Read: Books of Jacob, chapters 22-24

"by telling the story of the world, we are changing the world"

Welcome to the Slow Read Along of Olga Tokarczuk, The Books of Jacob. You read along at your pace, and I guide you through the story, characters, and rich historical and cultural context.

This week, Chapters 22 to 24, ending IV. The Book of the Comet and beginning V. The Book of Metal and Sulfur. We meet Jacob Frank’s grand inquisitor and anti-Jewish propagandist, Gaudenty Pikulski. Jacob becomes not a celebrated Polish lord. He is interned in the spiritual heart of Poland at Częstochowa.

The Books of Jacob was book 52 in my unordered list of 100 Books to Read Before it is Too Late. I hope you come to love this book as I do.

Olga Tokarczuk won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2018.

Critics described The Books of Jacob as a “decade-defining book.”

Special Note for New Readers and Subscribers

You can check back and catch up on the whole Slow Read of The Books of Jacob, with hyper-linked lists of all posts, profiled characters, and guides on my Slow Read page.

If you are checking in on the Slow Read of The Books of Jacob for the first time, check these guides to this brilliant novel, the best historical fiction of the twenty-first century, in my humble opinion.

13 January - Tips on how to do the 'slow read' of The Books of Jacob

20 January - An overview of the characters of The Books of Jacob

27 January - Historical context of the 'Other Europe' in The Books of Jacob

The Story: Chapters 22 to 24

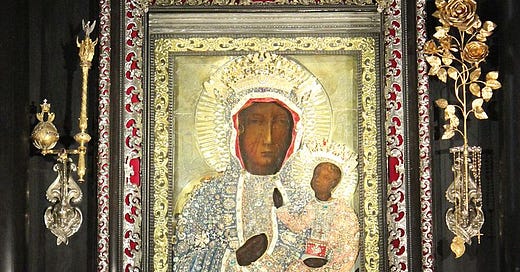

These three chapters conclude the Book of the Comet and begin The Book of Metal and Sulfur. The unexpected outcome of Jacob Frank’s conversion is his imprisonment in one of Polish Catholicism’s holiest sites, Częstochowa, the Pauline monastery and fortress erected in 1382 on Jasna Góra or Bright Mount.

In Chapter 22 there are thirteen sections which concentrate on Jacob’s story after his conversion and disgrace. He is accompanied by Moliwda, supported by Kossakowska, and investigated by Father Pikulski. Jacob and Moliwda flee to Warsaw with the aim of securing an audience with the Polish king to grant the Frankists land. Jacob enjoys the sponsorship of the Polish nobility and spends lavishly. Like many gurus, he indulges grandiosely and slowly loses touch with reality. Moliwda does not inform him of the reality that the Polish authorities are spying on him. Kossakowska attempts to integrate the Frankists as “Puritans,” thinking of the American settler dissidents, into Polish society. But Hana maintains her distance from converted life. Pikulski interrogates Shlomo Shorr and other converts and suspects their faith is a superficial disguise. The Bernardines, the religious order to which Pikulski belongs, arrest Jacob and interrogate him. Slowly Jacob loses his confidence. Moliwda witnesses the questioning and is then himself interrogated. He succumbs to pressure and reveals all that he knows about Jacob Frank. Moliwda again betrays the one he loves.

The short Chapter 23 (only three sections) concludes the Book of the Comet with three separations from Jacob—Moliwda, Nahman and Hana. Moliwda’s testimony against Jacob saved him and secured him the office as asecretary to Primate Łubieński. But his official career is a kind of prison in which Łubieński expects him to provide information on the heretics. Nahman is summoned to an interrogation. He confides his ambivalence about Jacob, both Messiah and abusive lord, to his Scraps and under the pressure of interrogation and self-doubt gives the Bernardine interrogators what they want. Hana is a prisoner in the invented Polish Christian identity that Kossakowska has constructed for her in her noble estate. She resists passively, delaying her baptism.

Chapter 24 begins The Book of Metal and Sulfur and has twelve sections. Jacob’s downfall accelerates, driven by his character flaws and the cascades of history. Jacob is beaten and sentenced to an internment, as an internal enemy, in the Pauline monastery near Częstochowa. From his cell he watches the pilgrims visiting the monastery, including its Black Madonna. He has servants and slowly charms the prior and guards to provide him abnormal privileges, including writing to his family. After writing a letter to Hana, news spreads that Jacob has survived persecution from the authorities. He was not dead as they feared. Shlomo visits Jacob in his prison, and sends gifts, including Father Chmielowski’s New Athens. The priest’s odd encyclopaedia becomes the text through which Jacob Frank learns Polish. Coincidentally, Chmielowski’s friend Drużbacka visits the monastery in which Jacob is a privileged prisoner. She is devastated by grief because her daughter has died. She prays uncertainly before the Black Madonna shrine. She smelts her jewellery into a golden heart that is draped over the Madonna. There she meets the “imprisoned Jewish prophet,” Jacob Frank. She asks him if he is capable of bringing the dead back to life.

There is so much pain on view here, Drużbacka’s own pain just a drop in the sea of tears that have been shed in this place. Every human tear enters a stream that flows into a little river, and then the river joins a bigger river, and so on, until in the end, in the great current of an enormous river, it washes into the sea and dissolves on the horizon. In these hearts hung up around the Madonna, Drużbacka sees mothers who have lost, or are losing, or will lose their children and grandchildren. And in some sense, life is this constant loss. Improving one’s station, getting richer, is the greatest illusion. In reality, we are richest at the moment of our birth; after that, we begin to lose everything.

Books of Jacob, pp. 296-295

Question for Readers

There is a telling passage about story-telling towards the end of the Book of the Comet. It is part of the memoir of Nahman, christened Piotr Jakubowski, “Scraps: Of the three paths of the story and how telling a tale can be its own deed.” He describes three paths at a crossroads. The middle path is the simplest, for fools, focussed only on facts. The right path is for the over-confident who trust their experience and their senses. The left path is “for the brave, the desperadoes, even—that one will be full of traps, potholes, hexes, and calamitous occurrences” (p. 334). The left path is the path that Nahman and Tokarczuk and even myself take.

The path to the left is only for those who have shown they deserve it, those who understand what Reb Mordke always said—that the world itself demands to be narrated, and only then does it truly exist, only then can it flourish fully. But also that by telling the story of the world, we are changing the world.

Books of Jacob, p. 333

QUESTION FOR READERS:

Do you believe that by telling the story of the world, we are changing the world?

Below the paywall, I have some additional notes for paid subscribers on:

Character - Father Gaudenty Pikulski, whose interrogation of the Frankists founded a strand of European Anti-Semitism

Context - Częstochowa, the holy site of Polish Christianity whose Black Madonna finally connects the story of Jacob and Elżbieta Drużbacka.