Where to begin a program of reading in the history of China? For the time-pressured reader, The Shortest History of China is a very good place to start.

Paid subscribers can join me for a live call on Monday to recap on the American world tour - after Liberation Day! Upgrade to paid now if you’d like to be emailed the details.

There are, of course, many other doors we could choose to begin this world history tour. We are badgered by many guides. But Linda Jaivin, The Shortest History of China is a great solution to a problem that you as a curious reader may have. With so much to read, where do you begin?

China’s history is long, intricate, and estranged by both ideology and language to many Western readers. As I discovered a few years ago, the curious reader, who wants to overcome these barriers, is quickly overwhelmed by pedantic reading lists, intimidating traditions of Sinology, and recommended texts that are exceptionally long indeed.

Linda Jaivin has brilliantly condensed China’s history into 250 pages of sprightly narrative full of surprising characters. She is a translator and novelist, rather than an academic historian. She brings the many stories of plural Chinas to life. You can read the book in a week, or even one weekend. You will finish inspired to explore further and pursue her recommendations for where to search for surprises.

The even shorter Shortest History of China

The book is divided into 15 chapters, chronologically tracing China’s history from its mythological origins to the modern era under Xi Jinping. Key dynasties and periods covered include:

Zhou 1046–256 BCE

Qin 221–206 BCE

Han 206 BCE–220 CE

Tang 618–907

Song 960–1279

Mongol Yuan 1271–1368

Ming 1368–1644

Manchu Qing 1644–1912

the first Republic of China 1912–1949, and

the People’s Republic of China since 1949, in three acts of Mao, Deng, and contemporary China.

Jaivin weaves an engaging story through this dynastic structure. She emphasizes patterns of unification, prosperity, corruption, and rebellion across dynasties. She artfully introduces the reader to the literary and cultural traditions of China as a ‘civilization-state,’ including tea, silk, poetry, novels, gardens, governance, war, peace, commerce, and varieties of Confucianism, Daoism and Zen. She incorporates often-overlooked narratives of women, rebels, and dissidents. That is her style, as you will see in the video below. We meet both the father of Chinese history and the mother of Chinese history. We meet poets and protestors. We meet the real-life characters who appear in stories and performance traditions of the Beijing Opera, which inspired my favourite film of Chinese History, Farewell My Concubine. We meet both the leaders and the dissidents of the People’s Republic of China.

If, like me, you like to season your history with the spices of literature and poetry, Jaivin’s Shortest History is a fantastic guide to one of world literature’s deepest traditions. As a reader who know no Chinese language, I really appreciated her advice on how to appreciate Chinese literature and to pronounce Chinese words. She conveys the calligraphic magic of Chinese poetry. She introduces you to the main writers of the classic and modern traditions. She leaves you confident to try reading a classic, like The Story of the Stone, or a modern claimed by many, such as Lu Xun.

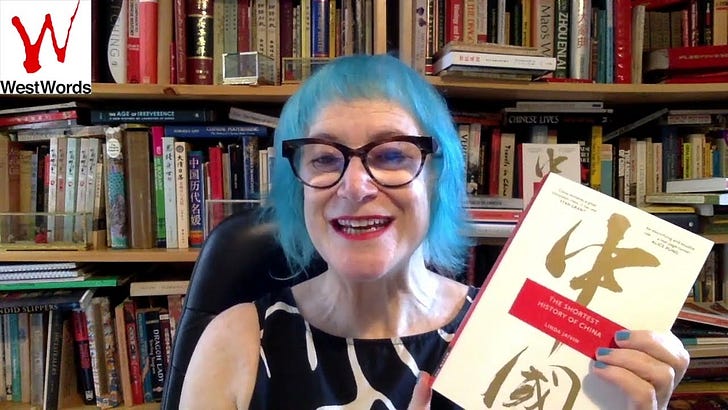

You can watch Jaivin herself describe her approach in this video, in which she also reads from the start of the book.

My Highlights from the Tang Dynasty

One highlight for me was the chapter on the Tang Dynasty. It includes the story of Empress Wu Zetian (r 690-705), and a portrait of the vibrant cosmopolitan capital of the Tang Dynasty, Chang’an, the place now known as Xi'an. Poetry, Chinese theatre, gardening, gender relations, even forensic medicine thrived in this time. This cultural capital of the then multipolar world became the model for the city of Kyoto, which I visited last year. History weaves a magic web.

The embrace of plural perspectives in the Tang Dynasty is celebrated by Jaivin. She celebrates its surprises and laments its shutdown, whether by the Song or the sterner ideological variants of modern China. Towards the end of the book, she writes:

“China’s human, cultural and economic potential is limitless. The CCP under Xi Jinping’s leadership believes that the PRC can fulfil this potential without relaxing - and while even tightening - its control over Chinese society, culture and intellectual life, and suppressing minority cultures and populations.”

I am not sure that judgment is right. We can discuss over the next eight weeks. Klaus Mühlhahn’s more scholarly, sober Making China Modern may be a better guide to how the institutions of modern China really work. That is why I have chosen it as the focus of my deep dive. But the traumas of history are more bearable when enlivened by the plural spirits of poetry. For that reason, Jaivin finds the Tang dynasty’s cultural flowering—including the three famous poets, Wang Wei, Li Bai, and Du Fu—to be an exemplary model for modern China.

She continues, after chiding Xi’s control of modern China’s life of the mind,

But historically, China has flourished most in times distinguished by their diversity and openness, such as the Tang dynasty. And what we think of as Chinese civilisation is the product of myriad interactions and exchanges between the Han and the peoples and cultures of Central Asia, the far southwest, the northeast and beyond.

The world has always been multipolar. And so too has been China.

Going Deeper: Confucius and a Modern Master

At the end of the book, Jaivin gives a guide to further reading. She acknowledges the influence of her “great mentor, occasional collaborator, one-time husband and lifelong friend, Geremie R. Barmé.” His writings can be explored freely online at chinaheritage.net.

If you go to that website today you will find an article on the troubles of Trump’s America titled, “Dwell not in a Country that is in Turmoil — an Historian’s Warning.” The article cites a passage of a famous text from Chinese history, The Analects of Confucius.

The Master said: “Uphold the faith, love learning, defend the good Way with your life. Enter not a country that is unstable: dwell not in a country that is in turmoil. Shine in a world that follows the Way; hide when the world loses the Way. In a country where the Way prevails, it is shameful to remain poor and obscure; in a country which has lost the Way, it is shameful to become rich and honoured.”

This passage was translated by Simon Leys, whose translation of the Analects is considered by Barmé the best. Leys was a pen name for the great Belgian-Australian scholar, Sinologist and essayist, Pierre Ryckmans. Ryckmans inspired Barmé, Jaivin and many Australian and international students of China.

Next week in my “classic history essay” stop on the China World History Tour, I will be reading one of Leys/Ryckmans’ great essays on the history of China.

On Wednesday, paid subscribers begin the deep dive reading of Klaus Mühlhahn, Making China Modern (see my introduction to this complement to Jaivin in my post, China History World Tour Preview).

We will jump ahead in the story from the Tang Dynasty, over the Mongol Yuan of Kublai Khan and Xanadu, and over the brilliant Ming. We will land in 1644 and learn the story of the development of modern China in the first 180 years of the Qing dynasty.

P.S. Fortuitously I discovered in preparing this piece that Jaivin will publish Bombard the Headquarters!: The Cultural Revolution in China in June this year. It is a little late for the world tour, and I will be recommending another book on the Cultural Revolution in a few weeks. However, I will certainly be checking it out when it is published.

In fact, I will be interviewing Linda Jaivin herself!!

Thanks for reading

🙏🌏❤️

Jeff

Your artful introduction creates imaginative space for a rich cultivation of understanding Jeff. Artful teaching on your part is much appreciated. Thank you.

I just reread this post and am really enjoying your approach. The quote from Confucius was so very apt. Thanks for being a centre of calm discussion in a world of lies, , shouting stupidity, bias, and aggression.