When Ancient Civilisations become Modern Great Powers

Reflections on epic statecraft in India, that is Bharat

India, that is also known as Bharat, has become a modern great power. Its assertion of great power status, however, is not done by becoming like the West, or ‘modernising’ in the Euro-Atlantic model. Rather, this ancient civilisation is drawing on the powers of its own traditions. Even in its modern statecraft, it draws on the great epics that are thousands of years old, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.

It turns out these stories may enable India (that is Bharat) to adapt better to the multipolar world than the myths and fables of Western civilisation.

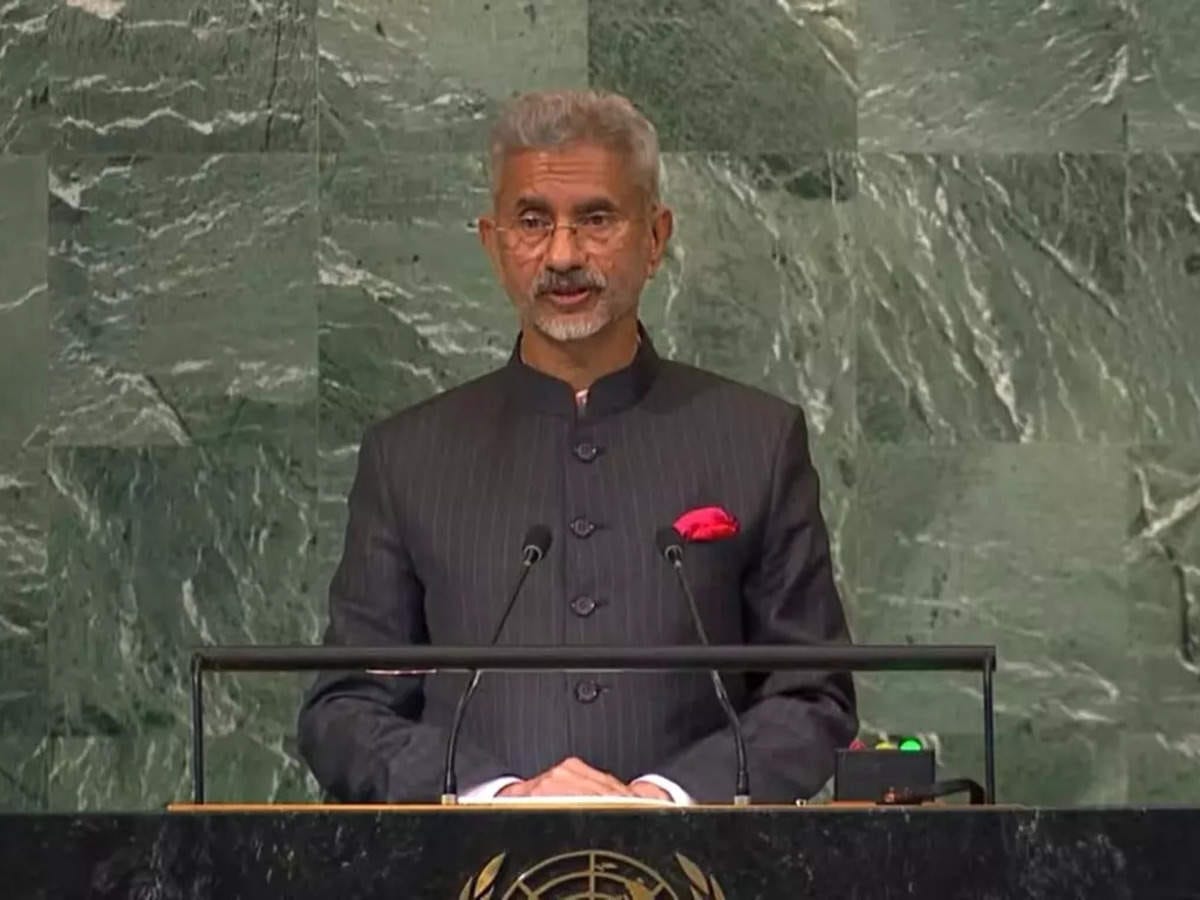

The idea of India as a ‘civilisation-state’ with its own traditions of statecraft was evoked during the week by its leading diplomat.

The External Affairs Minister of India/Bharat, Dr Subrahmanyam Jaishankar is one of the most insightful, authoritative, and accessible commentators on world affairs. More than that, he is at the crux of world diplomacy and one of the most eloquent voices who reassert the cultural, social and political diversity of the multipolar world.

For people interested in history and the cultural traditions of the multipolar world, he is also one of the most intriguing commentators. I gave some details on Dr Jaishankar in my Wednesday post, so do read that if you want a quick briefing on who he is and the substance of what he says in his two books: The India Way and Why Bharat Matters.

How India sees the multipolar world clearly

Many Western leaders struggle to see the multipolar world clearly. Many proponents of the multipolar world focus on how Russia or China see the changing world, However, the most insightful, authoritative, and accessible commentator, who clearly sees the changing world we live in, is the Indian External Affairs Minister, Dr Subrahmanyam Jaishankar.

During an interview with India Express this month, Dr Jaishankar expressed concern that parts of the world do not understand the traditions, culture, and history of Indian statecraft.

He referred in this clip to his use of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana in his books. They help to explain core concepts of Indian foreign policy to Indian citizens and the international audience. And they guide Jaishankar’s own thinking about the complicated world of competing powers and chaotic tides of globalisation.

In The India Way, Dr Jaishankar used the Mahabharata as a core narrative about politics, history, war, and the resolution of conflict that encapsulated Indian traditions of statecraft, especially the strategic culture of a rising power in a multipolar world. He commented on American and Western ignorance of the great epic, from which of course the Bhagavad Gita is drawn, even though its stories, embedded political philosophy, ethics and strategic culture deeply influence “the average Indian mind.” Such ignorance would not be tolerated in commentary on Western traditions of statecraft - ancient Greek thought (some of our classifications of political order derive from Aristotle’s Politics), or the ‘Thucydides Trap’, or myths of national liberation, or Machiavelli’s The Prince, or indeed The Bible - or to a lesser degree Chinese statecraft - Sun Tzu, The Three Kingdoms, Confucius, and, of course, Mao and Deng Xiaoping.

This needs to be rectified precisely because a more multi-cultural appreciation is one sign of a multipolar world. But also because many of the predicaments that India and the world face currently have their analogy in what is really the greatest story ever told.”

Dr S. Jaishankar, The India Way

He notes that pluralism is an ancient tradition in Indian statecraft, and that this contrasts to the ‘winner takes all’ approach of Western tradition, with its assumption there is always a hegemon, and its tendency to turn international rivalry into moral crusades. Moreover, the world of the Mahabharata was multipolar, and instructs us through its characters and narratives how to make wise, foolish, and dutiful choices in such a world. This old story can wise-up rulers and diplomats today.

Exploring the detail of Jaishankar’s comparisons with the Mahabharata and the Ramayana is a discussion for another day, though I do recommend reading The India Way as a primer on Indian foreign policy and contemporary world history. The main point that I draw out from Jaishankar’s comment is about divergence in cultural models for politics, and the varied resources within cultures for understanding and acting in the contemporary world.

There are more stories that can fire the political imagination than are dreamt of in Hollywood Marvel movies. The West is not always best, and our (Western) historical imaginations need to adapt to a changed world. Globalisation flows from the East, South and North, but less from the West. Ancient civilisations (India, China, Russia, the Islamic world, South-East Asia) have become or are becoming modern great powers. We need to develop new language and concepts to tell this history and to conduct our diplomacy.

There are clearly many in the West who struggle with this change. The Defenders of the Myth of Western civilization, who I discussed in “Is Western civilisation a myth?” are among them. So too are the many sunshine supporters of India in the West, who are not entirely comfortable with India making choices rooted in its own civilizations, religions, diversity, traditions, and majority opinions. For example, former Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Dr Peter Varghese, expressed the common elite Australian view that he prefers his India ‘secular, liberal and democratic’. He seems to want to hold his nose when talking about ‘Hindu nationalism”, the governing party (the BJP), the Mahabharata or even RRR.

On the other hand, there are commentators around the world who respond to this cultural turn away from the West with more than self-assertion and rightful anger at deep prejudicial condescension from the West. This can lead sometimes to brash myth-making about the ‘civilisation state’. For example, the popular and insightful commentator on geopolitics, Abhijit Chavda said some years ago:

India is not a Westphalian nation-state. India is a CIVILIZATION-STATE; has been one for millennia. Your "standards" don't matter to us.

Abhijit Chavda made similar comments in a recent podcast which I listened to this week. This concept of civilisation-state is emerging as a term to describe a great power whose soft power extends beyond its borders and is based in deep civilisational traditions. However, it is used in many varied and sloppy ways. It is often presented together with ideas of multipolarity as a challenge to the nation-state of the liberal rules-based order, or indeed as a challenge to the primacy or the myth of Western civilisation. In that it has a heritage. Famously, Gandhi once quipped that Western civilisation would be a good idea, if it ever happened.

in contrast, the establishment journalist, Gideon Rachman, as a defender of the West, criticised the concept of civilisation state as “illiberal”, largely because it challenged Western Primacy and came from the suspicious quarters of China, India, Russia, and Turkey.

The notion of the civilisation state has distinctly illiberal implications. It implies that attempts to define universal human rights or common democratic standards are wrong-headed, since each civilisation needs political institutions that reflect its own unique culture. The idea of a civilisation state is also exclusive. Minority groups and migrants may never fit in because they are not part of the core civilisation.

Gideon Rachman, Financial Times 2019

Rachman defends the liberal rules-based order fiercely against this rough beast intruder, but in his own way uses a cloaked concept of a civilization state, the West or the liberal rules-based order. There are also commentators who turn the idea of a civilisation state into a battle standard for the new multipolar world. For example, Alexander Dugin, Russian philosopher and geopolitics commentator (a hazardous combination), frequently comments on civilisation states, clashes of those states, and a new era of multipolarity.

I think before the concept of civilization-state is adopted we need to clarify another question. What is civilisation? In particular, the idea of civilisation-state has breathed new life into the misconceptions of civilization that were formulated in Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Huntington largely defined civilisation as religion and political world order, and he had a distinct preference for the WASP civilization of East Coast North America. These ideas of civilization, however, tend to turn civilization into a fixed state that is contrasted to lesser societies, rather than the complex process of adaptation and imagination that it really is.

By the way, I am exploring the concept of civilisation in my online history course World History Explorers I: Civilisations that you are welcome to join at any time by following this link.

Moreover, Jaishankar leans only lightly into the rhetoric of civilization state. He is a more subtle thinker than most geopolitics analysts. Indeed, he comments in The India Way that India may not even be a ‘civilisation state’: “India is also transitioning from a civilizational society to a nation state.”

I think it wiser to talk about cultures of statecraft, than civilisation states. But we in the West also need to accept that the world is big and diverse enough to have many varied traditions of statecraft. The traditions of the West are not always the best. The values of the West are not always primary. The new tides of globalisation are washing over our modes of statecraft too.

Drawing on the epics and ancient civilizational traditions of Indian statecraft, has enabled Dr S. Jaishankar to articulate a subtle, multilateral and intelligent strategy for India in a complicated world.

“This is a time for us to engage America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play, draw neighbours in extend the neighbourhood and expand traditional constituencies of support.”

Jaishankar, India Way

It beats dumb talk of democracy versus autocracy, or a war on civilisation, or Australia’s unthinking alliance with the USA, don’t you think? I wish Australian leaders could articulate something similar in our foreign policy.

Let us hope we see a symphony of civilizations in years to come, and not just ignorant armies, marching under the banners of the West and rival ‘civilization-states’, clashing at night.

Thanks for reading. Please share.

You might also consider supporting me by watching, liking or giving thanks at my YouTube channel, The Burning Archive.

I have just released my third audiobook reading on the channel. It is the first chapter of W.G. ‘Max’ Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, which I discussed in last week’s Saturday essay.

Superpower? In a country of 1408 million people, there are only 46.3 million people (3.28% of the population) who have salaried jobs in the formal sector, able to regularly contribute to their Employee Provident Fund. Of these, only half earn enough to pay income tax, and a mere one-tenth of them contribute to 80% of income tax collected. That too not by choice but by compulsion, because of tax deducted at source for their salary bracket.

The number of Indians who sleep hungry rose from 190 million in 2018 to 350 million in 2022, and malnutrition and malnourishment killed nearly two-thirds of the children who died under the age of five last year. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n08/pankaj-mishra/the-big-con

Two million slum children die every year as India booms

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/oct/04/india-slums-children-death-rate