“Persecution cannot prevent even public expression of the heterodox truth, for a man of independent thought can utter his views in public and remain unharmed, provided he moves with circumspection. He can even utter them in print without incurring any danger, provided he is capable of writing between the lines.”

Leo Strauss, “Persecution and the Art of Writing”, (1941)

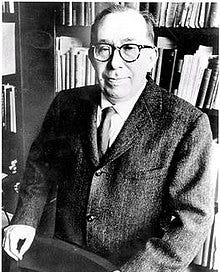

So wrote Leo Strauss, the American (if that is quite the right descriptor) political philosopher, amidst a world war and a holocaust of his people. His writing insists uncannily, despite all his erudition and esotericism, on being heard today as much as in that earlier crisis of authoritarianism, induced by Germany’s descent into hell. At the outset of “Persecution and the Art of Writing”, Strauss writes:

“in a considerable number of countries which, for about a hundred years, have enjoyed practically complete freedom of public discussion, that freedom is now suppressed and replaced by a compulsion to coordinate speech with such views as the government believes to be expedient, or holds in all seriousness.

Leo Strauss, “Persecution and the Art of Writing”, (1941)

He observes that most people in these previously democratic societies accepted the orthodox views propounded by what we might now call mainstream news and the credentialled media. So much so that even the limited form of freedom of thought for the majority – in Strauss’ judgement, “the ability to choose between two or more different views presented by the small minority of people who are public speakers or writers” – was practically constrained. Without this choice, societies enter the realm of persecution, marked out by the belief that lying by the culturally invested is not possible. The majority fall in with this theatre, much like Havel’s greengrocer (in “The power of the powerless”) putting out his sign calling on the Workers of the World to Unite, But there is a small minority who preserve genuinely independent thinking against the corrosion of this persecution by Red Guards, official orthodoxy, propaganda, distributed talking points, wokesters and mainstream news. Strauss calls this minority “the intelligent minority, to distinguish them from such groups as the intelligentsia”, and it is they who sustain free expression, both through sharing thoughts with benevolent, trustworthy and reasonable friends, and, when they do dare to express their thought, by doing so artfully, knowing the persecution that roams in the public domain. It is this practice Strauss calls “writing between the lines”.

Strauss is known for, and perhaps widely misunderstood because of, this idea of writing between the lines, of esoteric writing, shared by a small intelligent minority who encode and decode their heterodoxies in conjured thought and small seminars, disdainful of the common reader. It can seem stupidly elitist, but not if you appreciate the centuries of intelligent resistance to persecution that it honours. After all, Strauss was an expert on Maimonides (1135-1204), who practised a double life of faith in Islamic Spain, amidst the persecution of the Almohads, a fundamentalist form of Islamist ideology, before fleeing to Morocco.

Persecution of this kind has for centuries driven writers to speak indirectly to avoid punishment, to outsmart censors and and to communicate to intelligent unknown readers, not merely their own acquaintances. Strauss observes how persecution can vary in form from the Spanish Inquisition (an index of banned books and public burnings of heretics) to mild social ostracism. He lists some of the political philosophers from Plato to Kant who witnessed or suffered persecution more tangible than social ostracism, and who knew in their bones that free inquiry was dangerous. Liberal democracies might have forgotten the rub of this halter on their necks, but those who attended to the writings of East European dissidents, the actions of the Red Guards, and the sophistry of television journalists claiming to be trusted sources, never forgot how persecution sits well with our social instinct to conform, to mimic and to scapegoat.

In the eight decades since Strauss wrote his essay, “Persecution and the Art of Writing” tides of persecution have risen and fallen. We are clearly experiencing a stormy high tide right now – cancel culture, deplatforming, media hoaxes, twitter bans, social media rages, justice system breakdowns, soft authoritarianism, excessive public health rules, mask mandates, media manipulation, and the shocking attempt to cancel Russia. If the infinite conversation is to go on, it may well need to be conducted through the samizdats and esoteric writing of our times. Never has Leo Strauss, for all his strange arcane art, been more relevant to the intelligent minority who sustain truly independent thought in our time of troubles.

This essay will appear next year in my collection of essays on government, politics and life as a thinking bureaucrat, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Bureaucrat. I hope you have enjoyed this early preview on my substack.

My collection of essays on history, culture and literature, From the Burning Archive will be available from December 2022.

You can follow me on Twitter (@ArchiveBurning) and catch the Burning Archive podcast wherever you stream your pods.

Thanks for reading, and please spread the word aout The Burning Archive.