China, One-Child Policy & Population Ageing

Why you learn more about China from social history than economics

Western headlines scream “China population collapse” or “Demographic Doom Loop.” Doomsayers, like Gordon Chang or Peter Zeihan, claim the “statist” one-child policy cursed China to be too old, infertile, and unstable. The CCP’s own mistake undid the China model and imperilled the CCP. But, as the broken record of failed prophecies reveals, these China experts know nothing, about social history.

Welcome to the eighth and final week of my World History Tour of China. This week we look at contemporary China through the prism of a major social policy issue, population ageing. How is China adapting to the unique legacy of its One-Child Policy (1980) and to global demographic processes of population ageing?

During the World History World Tour, I am writing one post for each civilization state on a social policy or social history issue. On the American tour, I wrote about health policy, including substance misuse. On the China tour, I am writing about population ageing and demography. This choice comes from my professional background as a government official, who specialised in social policy, and as a historian, who specialised in social history.

Speaking of social history, I had the honour during the week to interview the distinguished historian of the Soviet Union, Russia and the Cold War, Sheila Fitzpatrick. Sheila is considered the founder of social history of the USSR, and the leading English language historian of the Soviet Union in her generation. We discussed her new book, The Death of Stalin. The interview will be posted on YouTube and Substack in the afternoon of 14 June.

I take this social policy/history perspective to offer a distinct insight on commentary on world affairs or geopolitics. The field is dominated by simple investor-friendly versions of economics and the game theory reductions of military strategy known as international relations or ‘geopolitical analysis’. These theories have their strengths, but they are not at their best when they stray into demography, social history, culture, or the enigmatic concept of civilisation.

Most predictions of China’s imminent collapse spring from such frail conceptual frameworks. It is no surprise, therefore, that they fall over. Peter Zeihan’s predictions of China’s collapse routinely gather up to one million views on YouTube. But they are always wrong (see my YouTube video comparing Zeihan with the more grounded Emmanuel Todd). Gordon Chang notoriously has cried wolf on China’s collapse for decades. In 2015, he wrote:

“Accelerated demographic decline is already evident, set in motion by the decades-old one-child policy. Beijing's vigorous enforcement of this statist planning measure has created population abnormalities that have already disfigured society and, in all probability, will do so for generations. China's economy, the motor of the country's rise in the post Mao Zedong period, is likely to be especially hard hit.”

Gordon Chang, “Shrinking China: A Demographic Crisis” (2015)

Ten more years of facts have not improved his vision. Recently, business oligarchs, such as Elon Musk, and favoured financial journalists, like Phillip Pilkington, have made similar arguments about fertility collapse in the West (as I discussed in this video). The China doomsters and fertility fortune tellers share a flaw. They interpret demography and government policy through blinkered made-in-the-USA economic models. When a society departs from the economic ratios derived from the post-1945 American experience, they are described as “abnormal,” “disfigured,” or about to collapse.

In The Defeat of the West, Emmanuel Todd reflected on how the illusory models and flawed statistics of economics have contributed to such predictions and the mistakes of Western strategic thinking. Reliance on the financialised GDP measure inflated Western leaders’ assumptions about the capacity of their economy to produce the weapons to fight their war against Russia. When real economies were tested, the Russian “gas station pretending to be a country” outperformed the West on both guns and butter.

Similarly, dated workforce and investment ratios (dependency ratios, prime working age, age-based consumption patterns), led the China doomsters to under-estimate Chinese society’s capacity to adapt to the processes of population ageing and the unique legacy of its One-Child Policy.

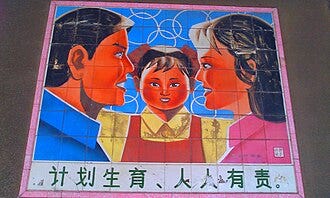

History of China’s one-child policy

Through Western eyes, the one-child policy is the iconic social policy of Communist China: repressive, statist, social engineering that had fatal unintended consequences. In my deep dive this week, “Contemporary China and the riddle of the modern,” I quoted the assessment by Klaus Mühlhahn, in Making China Modern that:

“The one-child policy might go down in history as China’s worst policy mistake in the post-Mao era.”

Klaus Mühlhahn

This is a reasonable judgement. One major study of the policy, cited by Mühlhahn, observed, “Like Mao's Great Leap Forward, Deng's one-child policy has created vast social suffering and human trauma.”1 In this account, the policy emerged from a tradition of population and birth control or “biopolitics” that dated back to the 1950s. From the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, during Mao’s most ardent revolutionary periods, the Chinese government applied its statist approach to birth control tentatively and intermittently. It was only after the great opening to the West during Deng’s Reform era, that the Chinese government applied Maoist social engineering to birth planning. The great reformer in his cowboy hat “represented the height of Leninist biopolitics—a politics of the administration of life by predominantly bureaucratic and mobilizational means.” In the Jiang era (1993–2003) birth control gradually shifted from Maoist crash campaigns towards market mechanisms and legal regulations. Under Hu (2003–2012) the one-child policy became less coercive and more oriented to policies of social security. Ironically, given all the talk in the West of Xi Jinping’s repressive regime, it was Xi who abolished the one-child policy in 2015 and went further by removing the two-child policy in 2021.

Historians, policy experts and demographers debate the one-child policy. It is a vast topic, and I want only to highlight some nuances left out of the “population collapse” scare campaigns that you read in the Western press.

First, the one-child policy was not the sole factor contributing to reduced fertility in China. The decline in fertility was driven by similar factors experienced around the world. China’s current fertility rate is broadly in the range of East Asian societies. Fertility decline and reduced population growth would have occurred without the one-child policy. Its greatest mistake was its unnecessary cruelty.

Second, the one-child policy had some positive effects. Greenhalgh and Winckler observe that “power over population has also been positive and productive, promoting China's global rise by creating new kinds of 'quality' persons equipped to succeed in the world economy.” This language is a little creepy, but it means that by constraining, and reversing, population growth China could invest more in education, social services, urban infrastructure, and workforce development for all of its citizens. Mainstream policy initiatives for the last forty years in the West have similarly focussed on “human capital.” I always found this phrase a little creepy too when I advised on it as a government official.

Third, the sociocultural effects of the one-child policy are difficult to interpret. Mühlhahn refers to the “little emperor” effect, meaning, with only one child in the family, parents treat their sole darling as a “little emperor.” There are similar popular sociological theories in the West, such as the idea that reduced fertility has created “helicopter parents.” I encountered many of these theories in my years working on government social policy. They are best taken with a dose of salts. Other effects include a gender gap arising from social pressures to prefer male over female children. These socio-cultural effects derive from many factors, some of which, such as gender attitudes, may indeed have contributed to the failed policy.

Fourth, the one-child policy was not made by the CCP alone. Indeed, Western thinkers and analysts advocated this idea. There were many motives and disciplines that converged to propose methods to control population: child psychology, economics, public health, and gloomy predictions by the Club of Rome. China’s poverty and large population provoked geopolitical anxieties about the size of the population in the non-Western world. Similar draconian actions occurred, with Western sponsorship, in South Asia and Africa.

Fifthly, China is clearly adapting to its demographic challenges. Its society looks increasingly flexible. Outside the febrile imagination of American prognosticators, Chinese society is no longer a repressive totalitarian state. The deep dive into Mühlhahn, Making China Modern has shown the mutual influence of a more complex society and more adaptive state institutions. The same story holds for the one-child policy and population ageing. China shares many characteristics of ageing societies all around the world. It adopts variations of common policies that are thoroughly researched by the World Health Organisation and United Nations. Its responses have strengths, weaknesses and mixed results. China has more old people than the USA. But then its people also live longer.

The contemporary Chinese policy response to population ageing is emphasised as a priority in the Government Work Report presented to the 2025 Two Sessions conference. There are proposals to boost the ‘silver economy’ (earning and spending by older people); to improve the elderly care service system, including promoting elderly medical services, community-based and home-based care, caregivers training and robotics development. Deficiencies in elderly care services will be tackled, such as urban-rural disparities, an insufficient number of care institutions, and an incomplete home-based care service system. There is a focus on using robotics as personal aids, and on improving the care workforce, health insurance, quality of caregivers, disease prevention, and long-term care.

But these challenges and policies are not exceptional to China. I have written similar ageing policy documents myself. Australia recently held a Royal Commission into aged care. We regularly interrogate how well we manage intergenerational equity. Several Asian societies share similar patterns of population ageing, intergenerational transfers, and public-private mixes of social security. China is not alone.

China is not experiencing a unique demographic crisis. Social and economic arrangements are changing to promote the “silver economy”, just like the West. Social security arrangements are being gradually reconfigured to reflect new working, caring, spending, and saving patterns over the life course, just like the West. Health and aged care services are being remodelled to meet demand, improve quality, and respond to the changed profile of illness and disability that arises when people live longer, healthier lives, just like the West.

Indeed, from my sampling of the policy documents informing China’s soon-to-be-released five-year plan for China’s social and economic development, China is adapting to the global challenges of population ageing better than the USA. Gordon Chang and Peter Zeihan might soon wish they were citizens of China or some European welfare states.

Better advice on China’s population futures

Social policy and social history are more complex than the simple models of doomster economics or the overegged punditry of geopolitical YouTube. When you next read screaming headlines about population collapse or demographic doom, whether the prediction is about China, or your own country, there are some simple things you can do to respond more intelligently.

First, trust the United Nations Population Projections, not the clickbait nonsense shared by Elon Musk. The United Nations Population Division publishes projections and analysis of major trends every year. They are your best source of advice.

The World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results contains ten key messages that are balanced, precise, and reliable. You can read the short summary in five minutes. You will be better informed than 99 per cent of geopolitical pundits.

You can check their data too. For example, from this page you can generate time series and projections for China, or any other country or region. Here are the stories of China and Europe. China is “collapsing” from 1.4 billion to 1.2 billion by the year 2050!

United Nations Population Division also publishes World Fertility 2024. It is an antidote to the pumped-up nonsense about the baby crash that Elon Musk and pro-natalist American weirdos have promoted in recent years, as I discussed in this video.

Second, remember that population ageing has changed many social dynamics over the life cycle. You need to think in time, across generations and with many complex interactions between social roles and human biology. Two-dimensional line graphs of misunderstood statistics that point to economic doom will only mislead you.

Third, check out Emmanuel Todd’s Lineages of Humanity: A History of Humanity from the Stone Age to Homo Americanus. It is a deep history of family systems across the globe and especially how the social developments since 1900, and the birth of the modern, have shaped the disposition of ‘advanced nations’. He focused especially on how the Anglo-American bias towards unconstrained individualism has roots in family systems, but is not a universal experience. He discussed, China pessimistically. Some of his individual conclusions may be astray. But he demonstrates in this work, as well as his now better known The Defeat of the West, that there is more to history and geopolitics than economics.

Todd shows how societies adapt to their own demographic conditions, but in the twenty-first century we have difficulty conceiving how much a century or two of modernity has changed the social character of humanity. We struggle to make sense of our world of ‘polycrisis’ because we have experienced:

“an anthropological mutation comparable to the Neolithic revolution even more than to the industrial revolution. Like sedentarization and agriculture, the transformation under way is causing an upheaval in the way of life of the human species in all its dimensions.”

(Emmanuel Todd, Lineages of Humanity, p. 5)

The elements of that mutation are not technology, the internet or AI. They are the stuff of social policy and social history:

Massive enrichment of all during the period 1920 to 1990 with regional variations

Sudden drop in the birth rate between 1960 and 1980 (yes, the contraceptive pill was released from 1960 and 1961 in Australia)

Increased longevity and ageing populations

Dramatic increase in educational level, with growth in higher education after 1950

Women overtaking men in educational terms

Terminal erasure of religion (his hypothesis on zero state religion is developed further in Defeat of the West), and

Collapse of the model of marriage inherited from religious times, marked sociologically (not morally) by the legalisation of same-sex marriage in many states from around 2000.

From Todd you discover why social history teaches more wisely than economics.

“If we take these transformations…, we gain a singularly enriched vision of the one-dimensional individual of the economists: we can maintain the hypothesis that human behaviour is rational while wondering what happens to the existential objectives of human beings when they become, statistically, richer, older, more educated, more feminine and less numerous.”

China is not going to collapse. It is adapting to deep processes that we also experience if in different conditions. China has challenges. But Chicago economics-based blueprints do not hold the answer. We will need to learn from each other while we make our way through this social upheaval that is the end of Western modernity.

I hope this series of posts on the world history of China can help you to do that.

This is the last post in the China leg of my World History World Tour.

Next Saturday, I will review the tour and reflect on some highlights. I will also offer a live call discussion session for paid subscribers.

From the following Saturday, we begin the India or South Asia tour. Over eight weeks, we will explore the award-winning Joya Chatterji, Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century, and pick up some highly recommended history books and Bollywood films as well.

From the start of the India tour, I will be integrating the deep dive and the weekly book recommendation post into a single Saturday post. As I flagged in an earlier post, I have been reviewing my content schedule to simplify and streamline the experience for you. This schedule will lighten the email and reading load for you and still offer the same insights and value.

Thanks for reading

❤️🙏🌏

Jeff

Susan Greenhalgh, Edwin A. Winckler, Governing China's Population : From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics (2005)

With famine in the rear view mirror, it's not surprising that in its early poverty China would try to limit population size. India provided a warning as to what a rapidly increasing population during extraction of the assets that could support it, could look like.

But feudal attitudes towards girls remained, now thankfully mostly gone.

Modern China has tech on its side. You don't need a huge work force when you have robot automation.

Just musing here, but if all the professional doom-mongers who wish for China's collapse blame a shrinking labour force for the impending downfall, then why would it need forced labour?