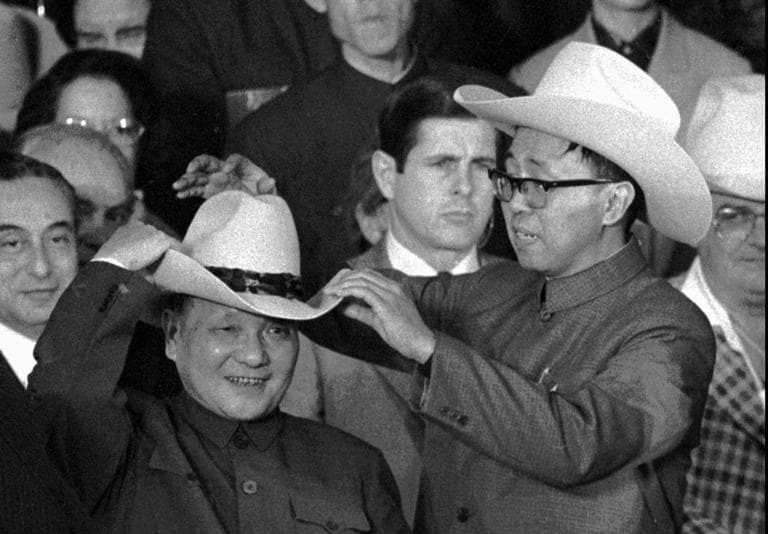

In 1979 Deng Xiaoping donned a cowboy hat on a tour of the USA. His hosts fell hook, line, and sinker for the lure they themselves baited: the illusion that China would become a New America. Meanwhile, China began to transform the world.

Welcome to the seventh week of my World History Tour of China. This week we look at the Great Transformation since 1976. How did China climb from the isolated chaos of the Cultural Revolution to become the major economic partner of the world?

Over those decades China has lifted one billion people out of poverty. Its citizens ride very fast trains, not simple uniform bicycles. Its universities dominate science and research league tables. Its movies like Ne Zha 2 outperform Disney’s Snow White, as I discussed in a deep dive on the American leg of the tour.

But to the disappointment of political and cultural elites in the West, and at least some within China itself, China never became a Westernised liberal democracy. In 1989, while the Soviet and Warsaw Pact societies fell in love with America, only to be rewarded with abusive shock therapy, China turned its back on Western democracy at Tiananmen Square. The political repression did not halt China’s rise. As Klaus Mühlhahn wrote,

Instead of simply representing a setback for reform, Tiananmen and 1989 permanently altered China’s reform trajectory. From then on, economic reform accelerated and expanded, based on centralization and the availability of inexpensive migrant labour. At the same time, stability and security became overruling prerogatives in political, cultural, and social life. 1

The horse of economic reforms rode on without the whip of neoliberal market ideology. The carriage of liberal democracy did not follow. Technological and cultural innovation occurred within the conventions of a socialist, one-party state. The fundamental axioms of Western political, economic, and cultural history could not solve the “China Puzzle.”

In my deep dive on Wednesday, I presented Klaus Mühlhahn, Making China Modern’s account of this great transformation. My book recommendation this week offers a second opinion.

Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian, The Great Transformation: China's Road from Revolution to Reform examines the ideological and economic shifts that defined China during the 1970s and 1980s. The book connects developments in periods—the Cultural Revolution and Deng Xiaoping’s Reform era—that are conventionally kept apart. It does so by using an historian’s narrative device of referring to a “long century” (as Eric Hobsbawm did) or “long decade.”

“The changes that took place during the “long 1970s” transformed China and, eventually, the world. This is a book about the first steps in that process: about how China went from being a dirt-poor, terrorized society in the late 1960s to one of hope and expectation by the mid-1980s…. It is the story of revolutionary change, in directions that almost no foreigners and very few Chinese could imagine when it all started. And, while laying out this rapid process of change, the book also attempts to explain how the earliest era of China’s reform and opening to the world laid the foundation for one of the most sustained and durable periods of economic growth we have seen in modern times.”

Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian, The Great Transformation

This story has a sting in the tale. It is a tale of success, but not without faults especially the political repression that in the authors’ view has increased since 2012. Since an economic miracle cannot be without qualification credited to a socialist, ‘authoritarian’ (a term I distrust) state, the authors must share the responsibility around. Like Mühlhahn, The Great Transformation highlights the interplay of domestic and international factors promoting China's rise, but it gives more weight to the importation of Western ideas. Like Mühlhahn, The Great Transformation acknowledges the way Deng Xiaoping led from the top by “crossing the river by feeling for the stones." But Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian give more credit to the liberalising, popular and democratic forces that Deng and the party could not control.

“A key part of this book is an account of how much of China’s reform and opening came from below and was carried out by ordinary people who rebelled against the earlier system in order to save themselves and their families. It is a story of economic and social revolution by Chinese who had had enough of dead-end political campaigns and lethal millenarian dreams. They themselves initiated the big changes that took place, both before and especially after political permission was given from the top. Much of China’s 1970s is a tale of how social, economic, and intellectual activism interacted with high politics to remake the country in unforeseen ways.”

Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian, The Great Transformation

To simplify to the moral kernel of this argument by two USA-based academics, the progress of China’s rise came from the people and despite the party leaders. Grassroots economic experimentation, such as clandestine agricultural reforms and small-scale trade, as far back as the early 1960s, laid the groundwork for later systemic changes, endorsed by authoritarian leaders. Deng Xiaoping took the credit, and exploited the power benefits, of local initiatives driven by ordinary citizens. Farmers and entrepreneurs tested market-oriented practices in the early 1970s, and defied state directives. Prosperous agricultural regions adopted work-unit incentives ahead of Deng’s official ‘visionary’ reforms.

At the centre of this story is the remarkable figure of Deng Xiaoping. Some years ago I read an intriguing book that described how Deng governed. Regrettably my notetaking practices were sloppy and I cannot now recover the title or author of the book. It did however convey a sense of the personal practices of Deng as a government official that this history by Chen and Westad tends to overlook.

Deng appears in this account as much more of a nationalist and a Russophobe or ‘Sovietphobe’ than I had previously realised.

To a surprising degree, Deng had taken over Mao’s general view of the world. In his estimation, the Soviet Union was an implacable enemy of China. It was also an imperialist superpower on the rise, with an endless appetite for territorial conquest built into its revisionist ideology. It could serve neither as foreign friend nor as an economic model for China, Deng insisted.

This congruence with standard “neoconservative” Washington foreign policy thinking nourished a fatal illusion among American elites. Commenting on how Reagan interpreted his doubtless stage-managed visit to homes in China in the early 1980s— "It could have been in any home in America” —Westad and Chen comment, “The fantasy that China was well underway to becoming another America in Asia was already developing fast.”

But Deng is not the hero of this history. His accession to leadership was a result of a “void of competence and bold plans for the future.” His longevity in the leadership came from the decent Hua Guofeng’s willingness “to step back peacefully” and the authoritarian Chinese political tradition. “As always in Chinese history,” Chen and Westad write, that tradition drove “a profound sense that China needed one top leader, a ruler who could be a trusted court of last resort on all things that mattered for the state.” To American scholars in the New Cold War, the Chinese still love their “Asiatic despotism”, just as Russians love their sacred tsar.

But Westad and Chen deny the party defined the vision that transformed China.

“In the early 1970s, well before any kind of meaningful reform plans were visible in Beijing, people rebelled against economic and social stagnation in a market revolution from below.”

It was these rebel yells, and not the technical plans of party bureaucrats, that made China great, in these historians’ view. The “revolution from below” Westad and Chen conclude, “did more to change China than any orders issued by the CCP.”

The book is based on research in Chinese archives, which the authors complain has been restricted in recent years. Written by a distinguished historian of the Global Cold War and a biographer of Zhou Enlai it is less focussed on the Reform era than the title suggests, covering the Cultural Revolution and international politics more than the years since 1984. This focus creates an optical illusion or perhaps an historical mythology of a “market revolution from below.”

I am more persuaded by Mühlhahn’s more comprehensive account in Making China Modern, including his emphasis on the profound institutional reforms of the 1990s that were definitely not the result of a “revolution from below.”

The last pages of the book wander into unbalanced claims against China under Xi Jinping’s leadership, especially its foreign policy. These claims are not substantiated by the book as a whole. Referring to geopolitical conflicts and social tensions in contemporary China, they write:

“Not everything in the new conflicts is the CCP’s fault. But the fact is that China today is more isolated internationally than at any time since the early 1970s, in spite of its massive economic outreach through the Belt and Road initiative. CCP leaders tell us that it does not matter, since the PRC’s foreign policy is correct. But, for the time being at least, the Party’s hubris in foreign affairs seems to mirror the return to megalomania in its domestic position.”

This statement reads a little like USA State Department talking points. The authors round off their mantra with the dream that China may yet take another path. They may have done better to edit their concluding homilies out. If you ignore those parts of the book, there is still a lot to learn from this history of China, even if it is fixated by the never-ending American fantasy of the long 1980s.

Thanks for reading

Jeff

PS Reminder you can book a free 1:1 call with me to discuss the two new programs I will be offering soon: Sprints or “mini-courses”, and a monthly group discussion. I have set aside times in June when you can book a free individual call with me to discuss these programs. You can schedule a 15-minute individual call on what would work for you right here.

I plan to launch both programs in late June or July and will send you emails with details of these programs over coming weeks.

Next Saturday, I discuss population ageing (and the One Child Policy) in contemporary China in the final leg of the World History Tour of China.

This coming Monday, the Slow Read of The Books of Jacob will look at chapters 25 to 27.

On Wednesday, the deep dive will look at Klaus Mühlhahn, Making China Modern and his account of China’s contemporary ambitions and anxieties.

Mühlhahn, Making China Modern, p. 448.

This is extremely useful - thank you.