Slow Read: Books of Jacob, chapters 16-18

“Poland is a country where freedom of religion and religious hatreds meet on equal terms.”

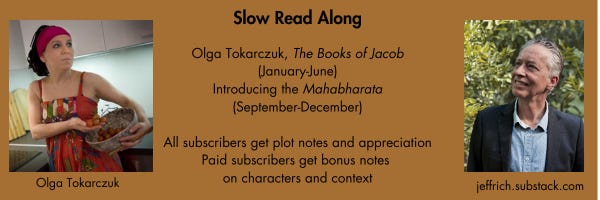

Welcome to the Slow Read Along of Olga Tokarczuk, The Books of Jacob. You read along at your pace, and I guide you through the story, characters, and rich historical and cultural context. This week, III The Book of the Road, Chapters 16 to 18. We meet Elżbieta Drużbacka and learn about the Seven Years War (1756-1763).

You may have noticed The Books of Jacob was book 52 in my unordered list of 100 Books to Read Before it is Too Late. I hope you come to love this book as I do.

Olga Tokarczuk won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2018.

Critics described The Books of Jacob as a “decade-defining book.”

Special Note for New Readers and Subscribers

You can check back and catch up on the whole Slow Read of The Books of Jacob, with hyper-linked lists of all posts, profiled characters, and guides on my Slow Read page.

If you are checking in on the Slow Read of The Books of Jacob for the first time, check these guides to this brilliant novel, the best historical fiction of the twenty-first century, in my humble opinion.

13 January - Tips on how to do the 'slow read' of The Books of Jacob

20 January - An overview of the characters of The Books of Jacob

27 January - Historical context of the 'Other Europe' in The Books of Jacob

This week I am again sharing the whole post with all subscribers to encourage engagement in the Slow Read and my other writing here at the Burning Archive. This is my gift to thank you for your warm response to my recent posts.

The Story - Book of the Road, Chapters 16 to 18

These three chapters take us to the end of the road for Jacob Frank and his followers wandering, from Türkiye back to Poland and then to a small village in current-day Moldavia. Chapter 16 begins with an outburst of book burning in 1757 in Kamieniec and Lwów (yes, another burning archive!), provoked by Polish religious hatreds and Jacob Frank’s heretical Judaism. Chapter 18 ends with the establishment in 1759 of a Utopian, cult-like community of Jacob Frank and his followers in Iwania, now Harmaţca in Moldavia. The Frankists appear to have settled in freedom, yet they are watched through the eyes of Moliwda, who seems to be both a faithful believer and a spy for the Catholic Church, whose leading bishop prepares the Frankists covertly for conversion.

In Chapter 16 there are thirteen sections that follow the varied reactions of some principal characters to the dispute between the orthodox Jews, Frankist heretics and Catholic Poland that followed the incident at Lanckoroń which I covered in my last context post. We see the reactions of and consequences for Moliwda, Jacob and his followers, Asher Rubin, Katarzyna Kossakowska, Bishop Kajetan Sołtyk, Sobla, Pesel, Yente, Father Chmielowski and his literary friend, Elżbieta Drużbacka. These events unfold in the context of a forgotten global war, the Seven Years War, which our immortal fourth-person narrator, Yente sees “will tip the scales that measure human life” (p. 625).

Jacob’s victory, facilitated by a secret deal with Bishop Dembowski, in the disputation or court case over the Lanckoroń incident leads to an outburst of book burning, anti-Jewish violence and religious hatred. Bishop Dembowski suffers for his bad karma. He is promoted for his scheme but soon dies. Without his protection, Jacob flees Poland. Asher Rubin protects his Polish Princess while serving the persecuted Jewish community of Lwów. Katarzyna Kossakowska urges protection and grants of land for the Frankist heretics, while Bishop Kajetan Sołtyk takes Dembowski’s place. Elżbieta Drużbacka writes to Chmielowski of the “imperfection of imprecise forms.” He shares his ambition to visit the great Załuski library. Then one night a bashed Elisha Shorr brings a cartload of books to Chmielowski for safe keeping. Frightened by the violence and book burning, Sobla and Pesel take the frail, immortal Yente to a cave “until it is safe.” Do not forget about this cave, in the shape of an alef.

“It is so beautiful and so cruel at the same time. A paradox that seems to be taken straight from the pages of the Zohar.” (Books of Jacob, p. 586)

In Chapter 17 there are thirteen sections that trace the growing conspiracy of the Polish nobles, especially Kossakowska, and Catholic Church to support the cause of the “Jewish Puritans,” but by perpetrating a blood-libel against Poland’s Jews. We also follow Nahman, Moliwda, Hana and the Frankists’ adaptation to the difficult cause of their heretical life. Jacob’s closest followers find him in Giurgiu in Türkiye. They convert to Islam, farm a small property, and consider returning to Poland with Hana and Jacob’s second child, Immanuel. Shorr retrieves his books from Father Chmielowski and gifts the priest a copy of Kabbala Denudata by von Rosenroth.

In Chapter 18 there are twelve sections which describe the life of the Frankists in their Ivanie community, the ambivalence of key characters, especially Moliwda and Nahman, towards Jacob as a cult leader, and the negotiation of the terms of an agreement with the Polish Catholic Church to do the unthinkable, to convert to Catholicism. Father Pikulski settles the plan with Archbishop Łubieński to convert these “dogs without masters.” Jacob and his followers may want to preserve their distinct blend of beliefs and customs. But the Church has other plans.

“Baptism is baptism… it must be unconditional. We must demand from them an unconditional conversion, no exceptions, and as soon as possible… The first to be baptized must be their leader, his wife, and their children. And with as much pomp and circumstance as possible, so that everyone hears of it and sees it. There can be no further discussion. (p. 499)

The scene is set for the Book of the Comet, and the conversion of Jacob Frank in 1759. Once again, as Tokarczuk wrote of the Lwów book burnings, “the capricious forces of the world have switched sides, for who knows how long” (p. 622).

Question for Readers

The symbolism of books pervades the Books of Jacob, and in these chapters the burning of books is a central symbol of religious hatred, cultural destruction, and yet also cultural survival. Stories of burning books, libraries and burning archives intrigue me. We associate them with Germany in the 1930s, but, sadly, they have been so much more common in history.

The sight of the burning books, their pages fluttering in the flames, draws people in, arrays them in a circle, like a magician at a fair who has ordered chickens to do as he says. People gaze into the flames and find they like this theatre of destruction, and a free-floating anger mounts within them, although they don’t know whom to turn it on—but their outrage more or less automatically makes them hostile to the owners of these ruined books. (p. 622)

QUESTION FOR READERS:

What is your response to the stories of burning books?

Character - Elżbieta Drużbacka

There are 120 or more characters in The Books of Jacob. Most are drawn from real history. Many of their names change through the novel. My guide helps you keep track of these dazzling character portraits.

Over the last 14 weeks I have profiled: Benedykt Chmielowski, Katarzyna Kossakowska, Elisha Shorr and family, Kajetan Sołtyk, Nahman, Jacob Frank, Yente, Sabbatai Tzvi, Reb Mordke, Hana, Tovah, Antoni Kossakowski or Moliwda, and Malka.

This week I profile Elżbieta Drużbacka.

Elżbieta Drużbacka is a poet, mother, governess and manager of the estate of a powerful Polish noble family. She maintains a writing life despite all those roles, and through her correspondence with Chmielowski we discover her hidden connection to Jacob.

In the tenth section of chapter 16 she writes a letter to Chmielowski that expresses her literary credo, her ars poetica. She concludes the letter by parrying the gendered assumptions of literary merit that her friend might have held.

You will say: “imprecise, idle chatter.” And no doubt you’ll be right. Maybe the whole art of writing, my dear friend, is the perfection of imprecise forms . . . (p. 591)

One senses Tokarczuk voices through Drużbacka her own philosophy about writing.

I believe that to express in language the vastness of the world, it is impossible to use words that are too transparent, too unambiguous—that would be like drawing a pen-and-ink sketch, transferring that vastness onto a white surface to be broken up by clean black lines. But words and images must be flexible and contain multitudes, they must flicker, and they must have multiple meanings.” (p. 593)

Drużbacka’s ambiguities, however, are for play and delight, not to dragoon the reader into some Joycean lifetime of academic study. After all, Drużbacka is a portrait of a woman writer in a time when women were formally excluded from the institutions of intellectual life. Her story is a wonderful portrait of how so many women wove an intellectual life around the gaps and margins of those exclusions.

We hear also a phrase from Tokarczuk’s epigram, or long subtitle, to The Books of Jacob in this ars poetica.

I do not put down my verses out of a hunger for profit, but rather that my readers might reflect and obtain some slight enjoyment. (p. 592)

Elżbieta Drużbacka was a real historical poet. She was listed in a 1933 list of 400 outstanding women, which noted her “outstanding place among the Polish writers of the eighteenth century” and the influence of the great Polish poet, Waclaw Potocki.

If you google her, you will largely get Polish sources. But with the help of Google Translate we can learn that:

Elżbieta Drużbacka was a Baroque poet. Initially, her works circulated among readers in the form of copies. In 1752, the Załuski brothers, creators of the Załuski Library, published a volume called A Collection of Spiritual, Panegyric, Moral and Worldly Rhymes…, which included the poet's three, currently best-known works, the novel The Story of Prince Adolf and several other minor works. These were the only editions of Drużbacka's works during her lifetime.

Moreover, from the same source you can read an automatic translation of her poems.

By some she is known as the Polish Sappho. Tokarczuk’s celebration of her in The Books of Jacob was well-received. You might wonder: what is her connection with Jacob? There is a hint in her history after death. Her manuscripts were kept in the Krasiński Library and were destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising. Yes, another burning archive.

Context - the Seven Years War

The historical and cultural context of The Books of Jacob is rich and yet strange to many readers. Discovering the history of the ‘Other Europe’—Poland, Eastern Europe, Judaism, the Ottoman Empire—is one joy of reading this novel. Going deep into Tokarczuk’s cultural perspective is one of its rewards. Each week I share a little of what I have learned by looking up names, ideas, references, and places on the internet as I read, and share snippets of quality history and literature as I reread.

Over the last 14 weeks I have shared vignettes on: the Tender Narrator, Rohatyn and the history of multicultural Eastern Europe, Polish society and nobility, the Szlachta, Jews in 18th century Poland, the Catholic Church in 18th century Poland, founder of Hasidic Judaism, Israel Ba’al Shem Tov, BeSh’T, the Frankist Movement, Sabbatai Tzvi and Sabbateanism, the Tree of Life and Jewish Messianism, Ottoman and Muslim Europe, European enchantment with classical antiquity in Polish culture, the Bogomils, the Shekhinah, and the real sex scandal in 1756 at Lanckoroń which Tokarczuk weaves into her story.

This week I explain why the beginning of the Seven Years War, noted on page 625 of the novel, was a global event that will reverberate through the rest of Tokarczuk’s narrative.

Evidently the world has become unbearable not only on the vast, open plains of Podolia, … It needed some sort of ending, some resolution. Besides, war broke out last year. Yente, who sees everything, knows that this war will last for seven years and will tip the scales that measure human life. The shift is not yet noticeable, but the angels have begun their cleaning: they take the rug of the world in both hands and shake it out, letting the dust fly. Soon they’ll roll it up again. (pp. 626-625)

How did this Seven Years War “tip the scales that measure human life”?

The Seven Years War (1756-1763) was a conflict between the major powers of Europe, with Austria, France, Russia, Saxony, Sweden, and later Spain siding against Great Britain, Hanover, Prussia, and later Portugal. It spread globally, with coincident conflicts between these powers in South Asia and North America. In the USA it is known as the “French and Indian War.” On that continent, this war largely settled the boundaries and cultural identity of Canada; but do not bother informing Donald Trump.

The History Extra magazine has a simple guide to the Seven Years War, written a little provincially from a British perspective. (A better German account is here) The deeper consequence of the Seven Years' War, however, was how it recast the geopolitical map of continental, Central and Eastern Europe, especially the diplomacy of Prussia, Austria, and Russia, the three powers that would from the 1770s partition Poland.

The war had its origins in the capture in the 1840s of Silesia by Prussia, under Frederick the Great. Coincidentally (if you believe in coincidences, as Tokarczuk says), Silesia is where Tokarczuk grew up, lives and is setting her next novel. Prussia’s victories in the Silesian Wars began the Iron Kingdom’s climb to the summit of European power. But Austria, led by Empress Maria Theresa wanted the rich province back. So, the war began and, perhaps not unlike the Donbass today, reordered the world of diplomacy. By 1763 Prussia succeeded in retaining Silesia and elevated it to the status of a great power, permanently altering the balance within the Holy Roman Empire and Central Europe. Austria failed to reclaim Silesia but remained a major power. It sought new domains to compensate for the war’s blows to its status and finances. Russia played a decisive role, and made peace with Prussia, while securing its south-western border with the Ottoman Empire, in part through settling Novorossiya. Its influence in Eastern Europe grew, especially under the leadership of the exceptional monarch of the Russian Enlightenment, Catherine II, Catherine the Great. But Poland-Lithuania became the target for interventions, meddling and rival claims by the three great powers of Europe. The road to the First Partition of Poland in 1772 was laid.

In summary, the Seven Years’ War established Prussia as a European great power, weakened Austria, expanded Russian influence, and directly led to the political dismemberment of Poland, reshaping the map and power dynamics of Central and Eastern Europe. It also had cultural effects, including on the development of the Enlightenment and the role of minority communities in European great states.

We will watch these events unfold in the novel and see glimpses of these rulers, Frederick the Great, Catherine the Great, and most of all the dealings of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa with the heretic and convert, Jacob Frank.

Thanks for reading

🙏🌏❤️📖

Jeff

The book burnings in these chapters really struck me as a powerful symbol of a society in crisis. It begins with the destruction of the Talmud, but quickly escalates—intolerance breeds more intolerance until people are burning all kinds of books, often without knowing why (p.621–623). It shows how dangerous it is when a society tries to control ideas instead of engaging with them. The Talmud, for example, is described both as “mendacious and pernicious” (p.624) and as a book that asks hard questions (p.625), showing how texts can be both feared and revered. I was also struck by the contrast with Nahman, who knows many religious books by heart but has no knowledge of geography, astronomy, or philosophy outside his tradition (p.503)—a sign of how book burning and censorship keep people insular.

I can remember reading parts of The Boy in Striped Pyjamas by John Boyne to a class of children and them being utterly taken with the big fire and the excitement of flames and burning and then discussing what they would take out to throw on the fire. Anything but books because it was all about the fire. One child did say that now you could find the book online so you didn't need a physical copy but the cultural damage, fear and lack of understanding about the power of words and ideas were beyond their comprehension at that point.

I was very struck in Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris where the library and archives are burned in Sarajevo - the black butterflies being the burnt pieces of paper floating around the city for days after the fire that burned them. It is such a symbolic act to burn books but also, I think, a hatred that strikes deep. The desire to erase you culturally, your history and your art. Some of the very things that make us human.