Unlimited Empire and America’s Unipolar Illusion

Final part of my reading guide to the history of the post-1945 world order

My reading guide to John Darwin’s masterly brief history of the post-1945 world ends this week with events after the Cold War, the USA’s ‘Unlimited Empire’ and its belief that it had transcended history in the Unipolar Moment.

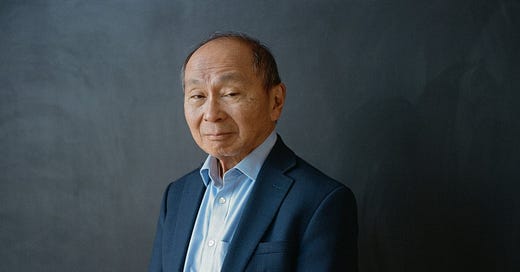

In 1989 when Gorbachev offered peace to conclude the Cold War, Francis Fukuyama dreamt big for America. The Cold War would become a frozen conflict, and history would end. The USA’s liberal genius had solved humanity’s political problem. American-style democracy would go global, if necessary, carried by high-powered AI-steered explosives. American culture would capture the world with the world wide web. The Partition of Eurasia by the USA after 1945 was now old news. The Washington Gang seized their chance to run the world from the White House Situation Room. The Unipolar Moment had arrived. America could do anything, even make its own reality, as Karl Rove infamously said. The USA had become the ‘Unlimited Empire.’ Or, at least, so it seemed.

The dream soon turned sour. The opposition quickly grew. Power slipped from the wizards’ grasp. The shadow of Tamerlane’s failure fell over the United States. As Darwin wrote in 2007, before the idea of the multipolar world became popular:

“If there is one continuity that we should be able to glean from a long view of the past, it is Eurasia’s resistance to a uniform system, a single great ruler, or one set of rules. In that sense, we still live in Tamerlane’s shadow - or perhaps more precisely, in the shadow of his failure. (p. 506)

Two decades later the truth of this long view of the past has been vindicated. But in 2007 Darwin’s scepticism towards the permanence of ‘one set of rules’ was rare. I recall myself from many discussions in university and government circles, the near complete consensus that believed in five tenets of the Unipolar Church of American Supremacy. American pop and the internet had created a global culture. The sole superpower had revolutionised military affairs. Its style of politics had made the world safe at long last for democracy. Its banks and technology firms had defined a new economy of bits and dreams. Finally, its leadership had entrenched the Atlantic Republic as a forever Reich through its self-defined single set of rules, the Liberal Rules-Based International Order.

None of those tenets are unquestioned today. The Unipolar Illusion looks like grandiose American bunkum today. But from the 1990s its geostrategists pursued this strategy of ‘full-spectrum dominance’ with ruthless zeal. The collapse of the other pole of the bipolar world also led to a mass-formation effect among Western intellectuals. The West had won. The West was best. The West had all the contracts and appointments. The diversity of ideas in the policy community and the academy narrowed. The infinite conversation of history did come to an end, at least in the newly expanded universities of the West. Intellectual debate forgot the culture of civil disagreement. Ketman prevailed, as Czeław Miłosz described it in The Captive Mind. People got by by repeating regime talking points. They made money by doing work for the national security community. Journalist historians like Anne Applebaum crowded out insightful students of the rise and fall of empires, like John Darwin.

So in 2007 Darwin’s speculation that American power might have limits was rare. Yet he was not alone, nor was he the first. One brave American international relations scholar, Christopher Layne, renamed the Unipolar Moment the Unipolar Illusion in its infancy in 1993. In “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Great Powers Will Rise,”1 he described the then still relatively modest ‘strategy of preponderance’.

This strategy is not overtly aggressive; the use of preventive measures to suppress the emergence of new great powers is not contemplated [JR: although this would soon change]. It is not, in other words, a strategy of heavy-handed dominance. Rather the strategy of preponderance seeks to preserve unipolarity by persuading Japan and Germany that they are better off remaining within the orbit of an American-led economic and security system than they would be if they became great powers. The strategy of preponderance assumes that rather than balancing against the United States, other states will bandwagon with it.

Thirty years later, we have witnessed the most catastrophic consequences of such “bandwagoning” among Western elites. Western leaders threw the rules of international order out the window after 2022, following the intensification of NATO’s war against Russia in Ukraine. A state power, likely the USA, sabotaged the Nord Stream Two Pipeline and German’s energy supply. “Bandwagoning” led to, in Emmanuel Todd’s phrase, the assisted suicide of Europe.

As an aside, Layne also laid out the real differences between the rival factions in American foreign policy, that has so confused people in assessing whether Donald Trump will be a “peace candidate,” opposed to the “neo-conservatives”. Biden pursues a strategy of preponderance by persuading allies to stand in the line of fire for the USA, including persuasion through covert operations and dirty wars. Trump pursues a strategy of heavy-handed dominance with open threats, bluffs and bluster, and more targeted business as usual with covert operations and dirty wars.

Layne’s 1993 article also supported my interpretation of the end of the Cold War. The USA never did end the Cold War. It just moved to one of its favoured “frozen conflicts.” Layne wrote, “In effect, the strategy of preponderance aims at preserving the Cold War status quo, even though the Cold War is over.”

The concluding section of Darwin’s history of the post 1945 world order is titled “Unlimited Empire?” Note the question mark.

It begins with the American response to the end of the Cold War. Darwin does not view the post-Cold War as an era of Pax Americana, of liberal democratic peace. Instead, he saw an era of global American expansion. A real end to the Cold War or a genuine peaceful order would have stymied American ambition. To end the Cold War with a peace, rather than a ‘frozen conflict’, would have stopped that expansion. It would have crossed the interests that relied on endless war. Critics call these interests today the “Media Academic Military Industrial Congressional Complex.” It is the strongest, most cohesive cluster of power in the fractured American republic.

Outside America, and especially Europe, the world wondered in 1989, would America retrench its undeclared empire? Would they follow Mikhail Gorbachev’s example in dissolving the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union? Would they do it with less haste and fewer mishaps? Darwin kicks the story off:

The great forward movement of American power and influence after 1945 would not be reversed. The Cold War had been the great age of American expansion. The vast new scale of American trade and investment, and America’s dependence upon imported products (especially oil), made it just as important as at the end of the Second World War to have a dominant voice in shaping the rules of the world economy. The geostrategic revolution brought about by air power, satellite technology and nuclear weapons affirmed even more forcefully that American security was a global, not a hemispheric, matter. Thus the American response to the end of the Cold War was to see it not as the chance to lay down an imperial burden, but as a metahistoric opportunity to shape the course of world history.

What happened next? Challengers emerged. Confidence waned. The swelling resentment at the burden of war led Darwin, in effect, to predict the Trump phenomenon. But in 2007 Darwin remained cautious about game theories that asserted an inevitable correction of the “imbalance of a unipolar world.”

In 1993 Christopher Layne was more brashly confident, as political scientists are wont to be. He argued that

the ‘unipolar moment’ is just that, a geopolitical interlude that will give way to multipolarity between 2000-2010.

His prediction was based on the game theory beloved by so-called realist international relations scholars: states balance against hegemons, even those that seek to rule by ‘soft power’ not force. The prediction seems stunningly accurate, if you test it by the date of President Vladimir Putin’s famous declaration of multipolarity at the Munich Security Conference in 2007.

But I prefer John Darwin’s more cautious predictions, and the reasons for them that are based not in theory, not in brutal ‘realist’ over-simplifications, but in the complex empirical stories of a long view of the past.

To learn how John Darwin more wisely read the changes of a multipolar world, please read on to my reading guide notes to the final section of “Empire Denied” in John Darwin, After Tamerlane. To read these notes, please become a paid subscriber now.